Symptoms of the Muse

| June 27, 2016 | Post In LEAP 39

Courtesy Georges Didi-Huberman

The question of the muse is, first and foremost, one of etymology. Our wispy shadows still draw us into the deep and blinding morass of history. The many gods of Mount Olympus are assumed to be older than history, which begins with their actions to protect humanity. Yet still more ancient than the Olympian gods were the goddesses known as Pierides, the muses who idled on Mount Parnassos. In Greek they were known as “Μουσαι” (Mousai), which shares its Indo-European root, “men,” with the Greek god Mnemosyne, the Roman goddess Minerva, and the English words “mental” and “memory.” In Hesiod’s work Theogony, the muses are the daughters of Zeus, king of the gods, and the goddess of memory, Mnemosyne. Although they were more respected and ancient than any of the gods, the muses were no different from the gods in the daily spirituality of the Greeks. Through sacrifices, celebrations, dramas, and various ceremonies, the muses were a constant presence in the lives of the people. In the contemporary imagination, the home of the gods is an illusory and unattainable world. For the Greeks, however, Mount Olympus was considered the starting point for all of history, a citadel and stage for every pivotal event. The will and actions of the gods directly impacted the history of the people and molded the world they lived in.

From their beginning, the muses tended to Greek ceremonies of worship and related techniques. Even before the Greeks used text, the muses ruled over learning. According to Hesiod and Homer’s descriptions, there were nine muses whose responsibilities were divided into fields such as history, astronomy, tragedy, comedy, and dance—the knowledges, arts, and, especially, literature. They could incarnate as dance or music, and writers and epic reciters prayed to them. At times they assumed the role of the storyteller, and the human writer acted merely to record everything they said. At the beginning of the Odyssey, Homer calls on the muses to sing for him the exhilarating story of the mortals who broke the gates of Troy. The gifts the muses bestowed on such worshippers were the arts of poetry, history, and memory.

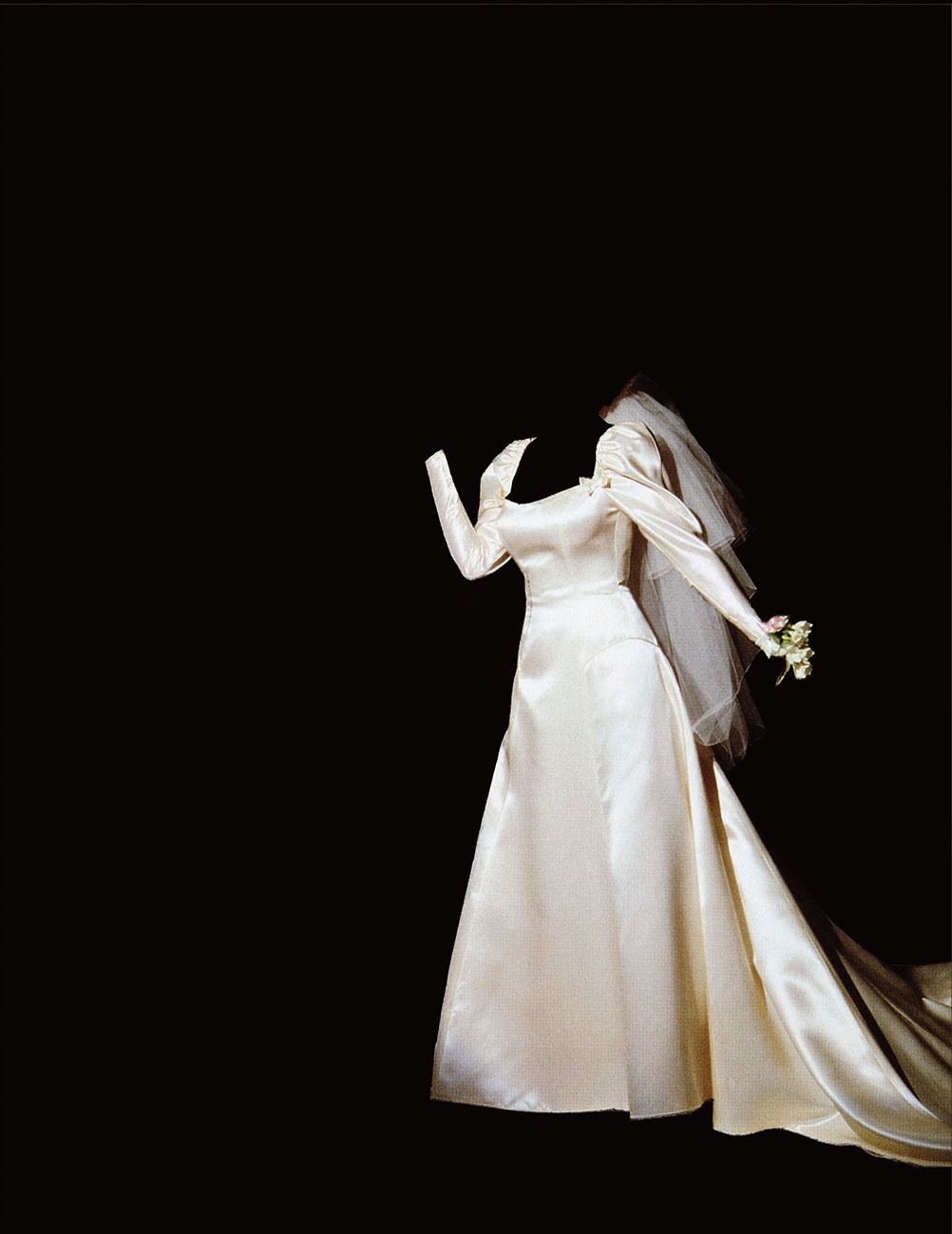

Courtesy Salon 94 and the artist

The one muse who lived on the earth was Sappho. Lithe, ecstatic, and a singer of incomparable splendor, she was considered by Plato to be the tenth muse. Though she was a mortal, her singing ability, knowledge, and sensitivity granted Sappho the divinity of a muse. She was a lesbian, a poet, and a figure adoringly worshiped by both men and women alike. She was the image of a perfect woman, living in a state of unending love and unbroken verse. This image corresponded closely with that of the gods, and therefore approached immortality. Even Horace said, admiringly, that her compositions were worthy of the holiest of praise, remarking, “Although they are / only breath, words / which I command / are immortal” (translation by Mary Barnard).

But Sappho, unlike the muses, was never incorporated into the ranks of the immortals. In fact, her songs were lost during the Byzantine Empire. The language and rhythm used by her followers gradually faded until it disappeared completely. As the Greek language of Homer and the Athenians washed away Aeolic Greek, Sappho’s dialect, a masculine language rose in its place. Sappho was no longer supreme, nor were the other muses. Early in Athenian mythology, the nine muses were entrusted to a male leader. Apollo, the sun god, used his golden lyre to conduct the muses in a chorus. Sappho was forgotten, perhaps because those shadows lurking behind the muses had been bleached out by the sun. The ancient chaos, complete with violent lineage, that the muses embodied was replaced and forcibly forgotten by the progress of civilization and an emerging order. A long era of patriarchy was beginning. The nine perfectly feminine faces of the muse resemble the women in the home who were compelled to submit to their fathers, husbands, and brothers. Beginning during this time, the muse became a paradoxical figure. They were goddesses but, like mortal women, were expected to look beautiful in a way that was pleasing to men. They had to obey the dispatches of their male superior, but they were also worshipped, loved, and called upon by men. In addition to their roles of childbirth, tending to others, and pleasing men, laywomen now had a new and invisible veil cast upon them: they had to become the muse. Controlled and needed, bound and adored, woman was a creation destined at birth to spiritual and physical trauma. She belonged to man. She was the man’s muse and the sun god’s muse. She had to satisfy every desire, every moral pursuit, and every sexual fantasy. The incarnation of beauty, she had also to lovingly care for the holder of the quill, the men who were building this hierarchy. She passed through certain images and texts, through the painter’s brush or the poet’s mouth. It went without saying that these artists were men. The muse became a male prerogative.

Courtesy Salon 94 and the artist

This muse is a product of the Renaissance, a result of the light cast by Apollo’s rational light. The nine muses possessed iconographic significance since Roman times, often holding flutes, scrolls, or other tools, but they had never before become the object of male desires. After the death of Dante, the muse sought to ignite the insights and passions of male artists. In Italy, motifs of artists lounging with muses began passing into the tradition of paintings. On the cover of Voltaire’s work, Elements of Newton’s Philosophy, published in 1738, a bright light issues from behind Newton’s head. The light is reflected off a mirror held by a muse and falls onto Voltaire, who is writing. The reality this signifies is that, with the help of his secular muse, Madame du Chatelet, Voltaire was able to introduce the story of Newton’s philosophy to France. Voltaire’s muse was exceedingly talented, but her posthumous reputation is only ensured by her connection to the father of the Enlightenment.

True ruptures and rebellions originate with another muse. It is the dark muse, the ancient muse who we have been pushed to forget. Their bodies call out to the eyes and desires of men, while their freedom reflects the insecurities and fears of those men. It is a fear of the rational order, a fear of the control imposed by masculine language, a subconscious terror at the thought of losing their privileged position in sexual relations. Like the rational muse, the crazed muse is born of ancient experiences in Greece that were forgotten or intentionally destroyed. It originates in a motherly power that is dark and unfathomably deep. In the shining rays of the Enlightenment, universalized by male speech and processed through truth and ethics, this feminine power appeared only in the masks of madness. It was a litter swept away by civilization, separated and dreaded. These are the tragic muses. Throughout the nineteenth century, the tragic muses are a constant in artistic and literary spheres. They are the mirror to men, reflecting desire and terror back to them. They are offered as a fount of inspiration, creativity, aesthetics, and life force which is called on by men, worshipped, and at the same time exploited and devoured. They are the sick girls under Rossetti’s brush, whose pursuit of drugs led to an early death. They are Rodin’s lovers, growing old in a mental institution. They are Picasso’s mistresses, weeping through unbearable hardship. And they are countless other unnamed muses who spent their lives wrapped in a tragedy that was their love for the arts. The tragedy is one man fulfilling his desire to control, his lust for power, his aesthetic projections. Women struggle throughout, and must constantly pay with madness for their efforts to see themselves clearly. The tragedy is gendered.

Courtesy Maccarone and estate of the artist

Through this, the image of Sappho finally reemerges. Led by the stricken, forward-thinking women, the modern Sappho is reborn at the turn of the century in the form of writers and creators who call on the feminine muse rather than the objectified muse. As a woman, Anna Akhmatova was able to speak directly with the muse, “I say to her, ‘Did you dictate the Pages / Of Hell to Dante?’ She answers, ‘Yes, I did’” (Muse, 1924, translated by Yevgeny Bonver). In his prose collection Less Than One (1986), Joseph Brodsky attempts to use the western canon to call out to the postwar world. He is unstinting in his praise of Akhmatova, calling her a wailing muse. At the time, Brodsky may not have realized that he and his peers were crossing the threshold into a new era in which both muses and calls on the muse would be swept along by a river of images and information. The muse is an enduring variable in the pragmatics of the new century. Depending on the value attached to her, she can even be mass-produced.

These fully new muses became, like large manufacturing plants, a symbol of the new era. Their constantly fixed smile is the boundary between them and the tragic goddesses of nineteenth-century Romanticism. These muses appeared first in ubiquitous advertisements—through posters, packaging, magazines, and television screens, they came to fully permeate the days and nights of urban life. The new muses cast off the images of the old. No longer are they frail, tragic creatures. The women of these advertisements are slender, robust, and take pleasure in exposing all the parts of themselves that the law allows them to, welcoming the attention it brings them. This attentive gaze is not composed purely of male desire; it also mixes in female envy. Where men fantasize of sexual conquest and occupation, women long for the same, embodying the modern muse. But becoming the muse still requires paying a price. Smile, hair, figure, and posture can be studied and imitated, but the final gilding for the lily has a different price. These are the physical goods, and the names of the manufacturers. Stockings, lipstick, and hair rollers adorn the new muse’s body, allowing every common girl the qualities of the muse for the right price. The muse became popularized, and was no longer the patent of Rousseau, Shelley, and Keats. Poets still longed for a muse, but the muse had been diversified into every body and appearance. Every person could have their own muse, and every woman could become one.

Courtesy Salon 94 and the artist

The brand new image of the muse did not reject tragedy, but its tragic colors had been neutralized. These were transformed into a fashion, a symbol, a consumable product. Factory girl Edie Sedgwick is an example of such. She is thoroughly worldly, not unlike the art and films of Warhol or the folk songs of Dylan. Keats’s nightingale was now the robin in every family’s television. But this worldliness and quality of daily life did not weaken Sedgwick’s fatal attractiveness. Instead, those small details (the smudged eye- liner, the fragile smile, the wide headband, the cigarette) combined into image of femininity that could be copied and distributed, at once attracting the opposite sex and satisfying the self. Muse became a synonym for style, and the muse was simply the emblem of a style. Karl Lagerfeld had his muse, and Jean Paul Gaultier his. Kate Moss became a muse, as did Natalie Portman. It was the era of the mass muse. The film and television industries, in particular, were the dream factories if not the muse factories, for to produce an image is to produce a muse. Now Apollo’s commandments had been disbanded. The new image of the muse was, in its rapid propagation, unbound and uncontrolled.

When the muse was no longer a proper noun or a set image, the contemporary muse turned her gaze to her own body. This body—sculpted, trained, meeting all requirements—existed both virtually and in the real world. It was a body in urgent need of acknowledgment and unidirectional gaze. The bodies put forth by the film and television industries today are, to a large extent, carriers and embodiments of the pleasure economy and identity exchange. Under the gaze of the camera lens, these female bodies that have no disposition, only humanity. It is an identity that can be applied, pandered to, and consumed. But who do these constructed muses belong to? Where does the desire for the muse and the pleasure it acts out arise from? Can the muse be rejected? Cindy Sherman took these ambiguities of identity into her camera, acting and simulating to create her images. The lens captures both the flesh of the female body and a vague appearance, like the muse that has yielded to the history and authority of disguise. Under the gaze of the lens or naked eye, Sherman’s body is connected to the illusory female figure of the muse. The reality between these two depends on two dimensions: the makeup acting applied to Sherman, and the true existence of that movie, that scene, that role.

The contemporary muse and the representation of femininity it embodies have long been an over-consumed symbol. They have been unceasingly produced, duplicated, and arranged until exhaustion, at which point they became empty signifiers. The catalyst and motivator for such a progression is the gaze (of the lens, the eye, or virtual reality). At this point, the pragmatics of the muse has developed to its zenith, and the word carries too many images and meanings. It is bogged down, and has become as fragile as glass. The muse as a feminine identity has likewise become muddled. What is a woman? Is she simply another kind of man established by custom and tradition (as in Judith Butler)? Just as the muse exists for the inspiration and rationality of man, so are women the natural, unsculpted disorder that has been inhibited and suppressed in the male body. They push men to a homesickness and horror which drives their eternal pursuit (as for Luce Irigaray), just as the dark muse holds within her the appeal of madness, the seeds of Bacchus. Perhaps the muse does not exist. As Lacan said, women do not exist. Instead, they are merely structures built by male phallocentric obsession, a citation or expropriation of the other, an imagined and desired partner, a subject writ small. The true female is forever missing. She is an image that cannot be described, a symbol that is constantly being replaced, an important other which does not exist and yet is everywhere in imaginations and desires. It’s true, we cannot say anything about the muse, nor can we say everything about the human. In this sense, the muse is simply a symptom of our condition.

(Translated by Orion Martin)