INDIA INK AND THE NEO-AVANT-GARDE

| November 16, 2016

Dada is not at all modern; it is rather a return to a quasi-Buddhist religion of indifference.

—Tristan Tzara

Conference in Weimar, Germany, 1922

As often pointed out by modern art historians, notably Bert Winther-Tamaki (2009),(1) the 1950s in the United States and Europe were a time in which numerous painters developed a particular interest for India ink techniques. This new “Orientalist” fad, rooted in a rather decontextualized and happily reinvented theoretical magma, revolved primarily around the issues of the line and the deliberate gesture. This medium and the imaginary world connected to it can also be found in the practice of artists related to American Abstract Expressionism such as Mark Tobey, Robert Motherwell, or Jackson Pollock; in that of “action painters” like Sam Francis or Toshimitsu Imai; and in the works of informal French artists like the “Western calligrapher” Georges Mathieu. More surprisingly, one may also legitimately detect the impact of India ink in more performative and conceptual—but also “technological”—art forms that arose in the 1950s and grew more established in the 60s, such as Minimal Art, happenings, and more extensively in the beginnings of performance art, Neo-Dada, Fluxus, or collectives such as Experimentsin Art and Technology (E.A.T.).

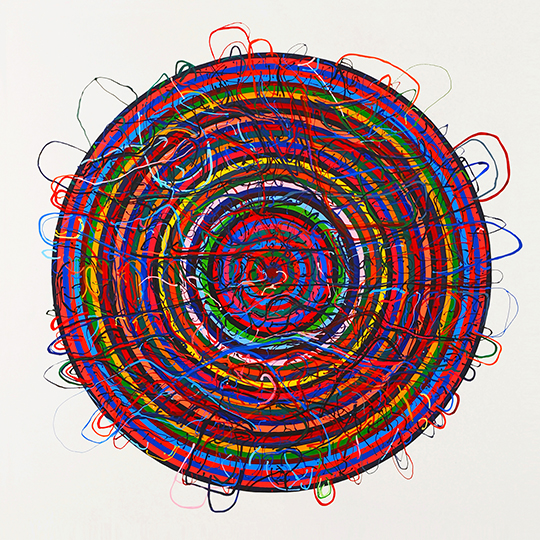

In 1955, in his thesis on American abstract Expressionism, the art historian William Seitz conceptualized the “calligraphic brush stroke” as “the irreducible pictorial unit” with the capacity to represent “nothing beyond itself.” (2) The theorization of an artistic practice based on “the brush stroke”—as opposed to form and representation—thus became a foundation stone at the time to express the intention to reach an “informal” abstraction, “emptied” of any thoughtfulness regarding the painting’s composition (thereby differentiating itself from more ancient abstract forms, such as Constructivism, Rayonism or Suprematism).

According to Winther-Tamaki, the “calligraphic brush stroke” as conceived by Seitz and many other artists and critics of the time was grounded in a very poor and unrefined knowledge of the historical and theoretical complexity of the practice of India ink as a medium. This conception was informed indistinctively by Chinese, Japanese, and Tibetan forms, mixing various ink painting typologies, from Shu-Dao (which originated in Chinese Taoist Buddhism) to diverse Southeast-Asian landscape painting traditions, and from Japanese Sumi-e or Suiboku-ga to Buddhist movements—especially Japanese Zen.

Two important figures fueled the rising theoretical interest of the New York art scene in the mid-1950s for ink painting techniques and Zen philosophy: Chiang Yee and Daisetz Teitaro (D.T.) Suzuki, who were both invited to teach at Columbia University at the time. The English art historian Herbert Read, co-founder of the London Institute of Contemporary Arts, described Chiang Yee as “one of the rare foreigners who have helped us better understand ourselves.” A close friend of the American art historian Arthur Danto, Chiang Yee is known for his opus Chinese Calligraphy (1938), which remains a standard reference work nowadays in the English-speaking world. As for D.T. Suzuki, he was a Japanese scholar who translated several ancient works from Sanskrit, Chinese and Japanese, and developed a syncretic approach to Japanese Zen philosophy.

Therefore, as early as 1952, while the use of ink as a painting medium and the philosophy surrounding it were topics to be found in the theories of many painters and critics close to Abstract Expressionism, other artists also availed themselves of the theoretical potential of ink to form a novel artistic discourse, which informed several post-modern movements: John Cage and the Gutai group. Cage, an artist, composer and “art guru,” discovered Suzuki at Columbia and became one of his most fervent disciples. Like Abstract Expressionists, he too grew interested in the notions of gesture and of liberated thought, and in the issue of matter, but all the while establishing analogies between Zen and the first pre-war European avant-gardes, such as Dada and the Bauhaus. He often recalled, around the end of his life, the impact that Nancy Wilson Ross’s lecture “Buddhism and Dada” had on him while he was a student in the 1930s at the Cornish School in Seattle. Ross was the wife of an architect, and had visited the Bauhaus in the late 1910s; in her lecture, she highlighted similarities between Piet Mondrian’s painted squares and the importance of empty space in Chinese painting. Her lecture closed on a quote from Edwin Rothschild: “Life is more important than art, but if we understood life we should have no difficulty in understanding art, which is its most eloquent expression… We want the artist to scratch our backs in the old familiar places, when we should be eager to mount behind him on his Pegasus, that we might see the world from his many points of vantage. We do not realize that the old familiar things were once new, spontaneous, even shocking, and therein lay the force and meaning of the spiritual energy which they embodied.”(3)

The “Orientalist” dimension of John Cage’s conceptions can partly be found within this lecture. Firstly, Cage was interested in the use of emptiness or silence as a means of composition, an approach that also appealed to the Bauhaus through the “Gestalt theory” (the psychology of form) and Laozi’s Dao De Jing. Cage’s piece 4’33” (1952), whose sheet music requires the pianist to open and close a piano top twice without playing a single note, so that the spectators may focus on the sounds occurring during those four minutes and thirty-three seconds, is the most famous example thereof. A second “Orientalist” streak, which could also be elucidated by 4’33”, is Cage’s attention to life rather than art, leading him to conceive the artistic experience as a springboard to better think or live ordinary life. Each of these two features materialized in many of the artistic movements Cage was involved in: experimental music of course, but also Black Mountain College, Neo-Dadaist movements in the United States and in Japan, Minimal Art in New York, or collectives such as E.A.T.

Another movement, born in Japan slighter later on (beginning in 1955), also reused the theoretical

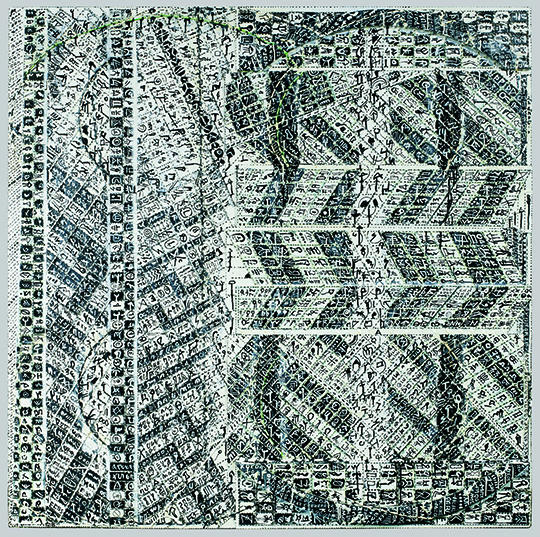

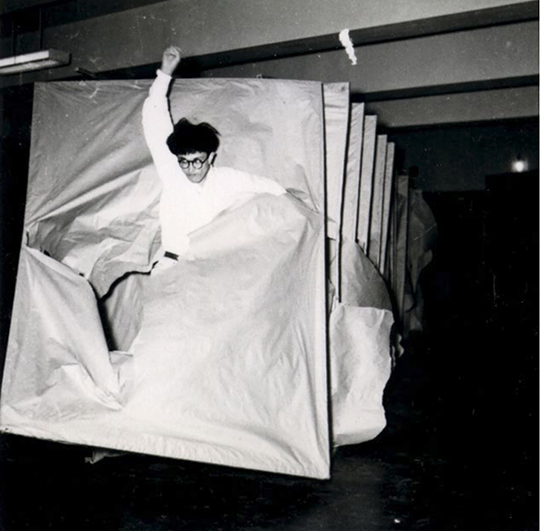

potential of calligraphy under new features: the Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai (Art Association of Concrete Art). The Gutai was founded and directed by Jirō Yoshihara. Its purport was “to do what no one ever did,” and to acquire a worldwide reputation. For Yoshihara, who was interested in more experimental and minimalistic calligraphic forms, such as Nakahara Nantembō’s works, calligraphy reigned supreme. Nantembō was a Zen monk from the early twentieth century who developed outstandingly the technique known as Ippitsuga (single-stroke painting), which he used for instance to paint his own self-portrait in a single horizontal stroke. The issue of stroke intensity, whereby action becomes art, but also experimentations centered on the materials suited to calligraphy as a Zen exercise, led the Gutai to produce visual performances that numerous Western artists discovered through the movement’s journals sent by Yoshihara all around the world, or in Life’s 1956 report. Thus it was that Jackson Pollock and a young Allan Kaprow, for example, discovered the photos of Saburō Murakami’s pierced paper canvas, Sadamasa Motonaga’s smoke-ring-making machines, Kazuo Shiraga’s flounderings in the mud, or Atsuko Tanaka’s sensory installations. While the French art critic Michel Tapié attempted to establish a link between Gutai and informal painting, and encouraged these artists to abandon their “hors-cadre” works, it was precisely such actions—discarded by the Gutai after 1958—that Allan Kaprow designated as an important source of inspiration for his happenings.

Therefore, India ink could be understood, within the context of the 1950s period, as a vehicle that found itself more or less torn away from its original context, but recharged with new concepts and perspectives by a great many artists around the world. Ink became a sort of theoretical “skeleton key” allowing very diverse artistic movements to make headway, follow their respective intuitions, and to explore the issues of action and emptiness through mediums other than painting.

1. Bert Winther-Tamaki, “The Asian Dimensions of Postwar Abstract Art: Calligraphy and Metaphysics” in Alexandra Munroe, ed. The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860-1989, (exhibition catalog) Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2009, pp.145-157.

2. William C. Seitz, Abstract Expressionist Painting in America: An Interpretation Based on the Work and Thought of Six Key Figures. Graduation thesis. Princeton University, New Jersey, United States, 1955.

3. Edwin Rothschild, The Meaning of Unintelligibility in Modern Art, 1934. Quoted in Kay Larson, Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists, Penguin Press, New York, 2012.