Mythology, The Feminine, and Sense Film: The Flashback that Begins with “Moving Mountains”

| March 1, 2017 | Post In LEAP 43

The original story of Yugongyishan (Moving Moutains), the legend of the old man who moved the mountain, is actually a rather romantic one. The story goes that an elderly man of over seventy, driven by a wish that his children and grandchildren should never be hungry or poor, moved two giant mountains to the side. This story of unflinching faith and conviction has been passed from generation to generation, accruing more grandeur and color with each transfer of hands. Xu Beihong’s famous painting of the tale became a classic image of modern art history. Mao Zedong’s proclamation of its name sealed it as the guiding principle and spirit of the program to build Chinese socialism. Now, the contemporary meaning of Yugongyishan seems suspended and distilled forever in the moment of its moral: the quintessential motivational picture of “man conquering nature.”

Yang Fudong’s reproduction of this classic narrative, using moving images, will startle audiences because it constructs the “real truth” of the mythological text in high-definition video. Here will be revealed the majesty of the mountain and the smallness of the man, the unbelievability of the action of opening up a mountain with only a hammer and axe, the inconceivable cycles of determination that have persisted through generations… But when sloppier oral recounting gives way to the conclusive and irrefutable reality of film, the entire old story breaks through the halo of romanticism that once enshrouded it, and the “real truth” only adds to the inflections of absurdity and dejectedness that the story holds. This mode of probing for truth within fictional frameworks of space and time, this alternation of the use of symbolism and realism, is something Yang’s films excel at. In his work, from the early Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest (2004-2007), to The Nightman Cometh (2011), to Moving Mountains (2016), there is often, to differing degrees, an appropriation and re-ordering of a historical script and the emergence of an ambiguous tension between jumps across time in narrative structure and the fluidity of subconscious reality. This tension allows our perception of reality to reach a depth that reproductions of reality rarely master and can only achieve through a “return” to history or myth. And perhaps only that irregular zone of “re-entry-overlap” itself can be the arrival of a more authentic relationship between individual, history and present reality.

The aesthetic structure of Yang Fudong’s work has been defined as “New Realism” by some circles of critics, but the artist calls it “sense film.” The name refers to that which can be “sensed but not expressed in words.” Ultimately, “sense film” is an attempt to extract and distill the poetry of words; but the attempt at abstraction does not exert itself over narrative, nor does it fall into exact analysis. It seeks only to perform a kind of measured expression. From another perspective, Yang is not the kind of artist who first establishes a purpose for words, then sets about abstracting them into poetry. On the contrary, he often begins with the abstract—he starts from a place of what he calls “formless aesthetic pleasure and a sense of what cannot be spoken” and from there endeavors to “move certain things forward.” As for what these “things” are, that is based on and gathered from the mutual exchange between the work and the audience. Yang himself is a member of this “audience” as well; acting as viewer in the delays of his own extended creative process, he gradually approaches the “truth” that the film itself opens up for him, and not the other way around. This outside-in approach, this move from the virtual towards the real, magnifies the artist’s experiments with filmic language over filmic content. This also explains why the overall “style” of Yang’s films makes such a deep impression, but it is rare to be able to pin down their exact positions. A continuation of his earlier “sense film” approach, Moving Mountains presents an extensive use of symbolic objects, landscapes, and characters—all of which can only be interpreted in isolation from one another. It is difficult to provide a summary or explanation of the work at the level of content. A symbolic approach is clearly suited to such a system; through the dismantling of narrative, it lifts any potential limits on the work’s ability to grow itself, while simultaneously providing a field within which “metaphor,” the structural modality of Yang’s work, can be further refined.

The exact proportions of so-called “sense” are not easy to grasp, however, which means that there is a tendency to overstep into doctrines of style or excessive infatuation with pretentious expression. We can therefore see the way in which the artist’s filmmaking practice in recent years has been a continuous debugging of his own system. Parallel to this debugging is an alternation between the distortion of collective awareness and of personal expression, which has persisted for several years. Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest is an extremely important coordinate in this geography, as it strikes at the heart of the collision between collective anxiety and individual bewilderment prior to the full-throttle acceleration of Chinese society. At the same time, the film adopts a strongly individualistic vocabulary (albeit a slightly choppy one)—using absurdist pictures to expose realistic encounters, melodious beauty to draw out anxiety, and aimless camera angles and performances to magnify individual nihilism. Furthermore, though the original story of Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove itself draws on traditional literati values, thoughts, and feelings regarding an ideal society, the lens in this version follows seven specific young individuals, and in doing so does not allow the sense of concern for country and society fall into the conventional stereotypes and impulsivity of grand narratives. Ultimately, everything points to the individual. This brings us to a problem that not only Yang Fudong but also every artist active in the creative field around the mid-2000’s universally faced: namely the issue of individual consciousness and individual, identity-based anxiety in the midst of social transformation. Yang found his own place within this process: “sense film” appropriately positions itself in the safe zone between suspended realism and not-yet-familiar abstract language.

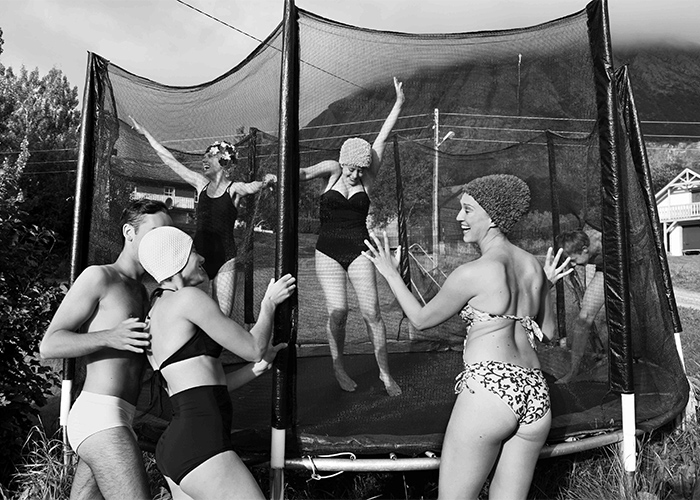

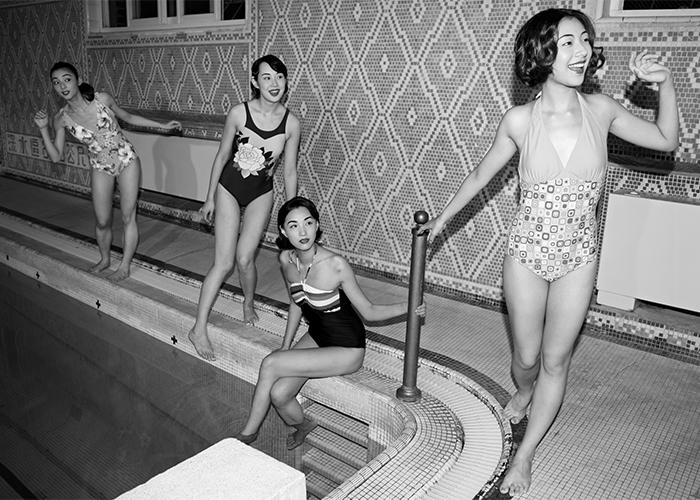

Carrying this burden of care for country and society brought creative inertia and the artist lost his own way a bit. In the films The Fifth Night (2010), New Women (2013), and several photography works that came out in the same period, such as International Hotel, Yang Fudong’s works increasingly show a tendency to mine the inner world of the individual. Under his lens, the “feminine”—more so than the “young women” in his early films—is exposed to reveal private emotions, desires, and behaviors. The work places more pressure on the poetic manifestations of individual subconscious and individual memory. There are two sides to this coin: on the one hand we find a gradual shift away from the artist’s concern for society in his works, on the other hand we see the continued increase of the accuracy and precision of an aesthetic language that is better able to express the individual spiritual dimension. And yet, it is perhaps inevitable that in the pursuit of an exact language and a particular image, the problem of pretense will arise. The artist’s works from this period show a kind of flourishing aesthetic saturation, one that made Yang’s personal style more and more popular, but caused some of his creations to get lost in the interest of satisfying taste—such that much of the earlier complex, subtle expression is easily reduced to surface “mood.” At this moment in Yang’s career, there is a decrease in the possible layers that “sense” film is able to convey.

Nevertheless, on the whole these transformations did open up the possibility of a sustained rhetorical expansion in Yang Fudong’s works, and pushed his experimentations with “sense film” to a more extreme place. This is most apparent upon arriving at The Coloured Sky: New Women II: a very unique piece among the artist’s creations. The first thing, and the hardest to miss, is the fact that prominently uses color amidst the artist’s typically heavy use of black and white. This is not just a matter of style; the neutrality of black and white images provides a security barrier for individual expression in most of Yang’s works. Black and white produces a kind of distance, and can be seen as a sort of protective layer between image and audience. In contrast, The Coloured Sky: New Women II moves “closer to childhood,” in the artist’s words. The film’s color saturation is at the level of “colored sugar paper” in the beaming sun: a brightness and vividness that bespeaks a kind of danger, a sharp edge. Somehow, too, the “purposely false-looking sets” of the film, in their slight detachment, more closely approach a kind of psychological “reality.” To date, this work of Yang’s may have gone the furthest in what it does with images of individual expression and corresponding adaptations of abstraction.

This level of practice leaves traces of itself in Yang Fudong’s creative system going forward. The presentation of individual memories and desires begins to emerge more boldly and naturally in Moving Mountains, averting the alienation of the encounter between individual subconscious and public sorrow over the ideal nation, its history, and the state of society. The first series of shots in Moving Mountains clearly presents this movement: in the story everyone is familiar with, the “old man” is the protagonist. But here, the first character that enters upon the scene is a young woman, a mother. Over the entire film it is her monologues and the shifting roles she plays that advance the plot forward. At the same time, it seems that she alone can be freed or dissociated from the plot, free to flee to the world beyond the screen. In reappearing motifs, her character is a fusion of protagonist, soliloquist, and even “audience”: a special, individual entity isolated both from the original text of the story and the reality of the film. The very existence of this entity produces a head-on collision between classical narrative and individual experience. This embedding of personal color and experience into narrative occurs in a more subtle and three-dimensional way here than in Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest or Fifth Night. Another noteworthy event is the repeated expression of “mountain” in the film, and the explicit placement of a sort of mountain-shaped “thing.” Yang seems to be particularly fascinated with mountains, or with compositional patterns in the shape of mountains. All kinds of “mountain” variants appear in his past works, and just understanding them as metaphors for nature would be overly generalizing and simplified. In many of his works, mountains echo each other from a distance, stringing together a kind of psycho-metaphorical map. With Moving Mountains, this map appears more adventurously and symbolically than before—it goes beyond the realist treatment of mountains, beyond the flattened mountain-morphologies. We notice the re-appearance of the tent-like mountain-shaped “thing” from New Woman II, for example, coming to us as if in flashback. It is hard for us to determine exactly what this “thing” is, but one thing is clear: in his use of symbolic forms, Yang is not limited to the realistic sketches and naturalistic approaches of his early period, nor is he entangled in simple symbolic relationships. Rather, he goes directly to the kinds of metaphors that most closely approach the structure of the psyche, by calling upon the sense of a sort of theatrical stage, and allowing more and more abstract “things” in.

Looking at Yang Fudong’s early creations, if Seven Intellectual in a Bamboo Forest is the most saturated with narrative structure or rhetoric among them, then Moving Mountains is perhaps the most like a “mirror” to the others. It provides a similar narrative foundation (a misappropriation of mythological texts), familiar plot elements and expressive syntax, and even more importantly, a focus on historical concerns and national “feelings”; to boot, the most significant plot line centers around the wanderings of a group of urban youths in the mountains. Both of these films share “historical misappropriation” as starting points, and both make speculation about plot seem roughly possible: will this one be about an intellectual’s reclusiveness or the return of the urban youth to the countryside? But compared with Yang’s earlier works, the direction Moving Mountains grows much more ambiguous and abstract. This is not only because Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest offers the archetypal story of the oracle and the scholar who go looking for an escape from the pressures of society; it is also because in Moving Mountains there is a convergence of further levels of external reality with contradicting levels of psychological reality, ultimately making it difficult for the audience to articulate at all clearly or specifically a metaphorical direction for the piece. This makes us only able to rely on the several, dispersed flashes of Yang’s “sense” moments, to feel a kind of hidden truth underneath poetic exteriors. For instance the woman who is present throughout seems to be very comfortable with her role as a peasant girl in the mountain village, but in one moment suddenly changes her clothing and now stands in a traditional qipao, putting us in a trance of chaos as we remember similar personas in New Woman and Fifth Night. Likewise, the urban youth ultimately shed their leather shoes and Western suits when they arrive at the mountain, and become mountain laborers once more; the reference is clear and obvious enough, but the echo of Xu Beihong’s oil painting rings somehow false, as if this return to labor is only a dream sequence, a slogan of sorts. Meanwhile, the actual “old man” from the original story is, in his rare appearances in this version, an elderly man with dementia. And just like that, the one certain character has become the least stable. Compared to the “wounded intellectuals” of his previous works—the youths in the mountains with their disorientation, struggles, and crying out; the young women drunk on their brightly colored dreams—the characters in Moving Mountains have all become more silent, contradictory, and complex. In other words, if the film does, as the artist states, intend to reproduce faith in the spirit of “determination,” what it reveals is that the certainty of truth and the pursuit of faith are in fact riddled with traces of conflict and contradiction, and that these traces are in fact what “sense” film is skilled at capturing. This may be even more the case when it comes to the riddle-like traces of social structures, of ideals, of human nature, and of time.

The culmination of the film is a magnificent scene at the end in which the oil painting Moving Mountains is reproduced: the one in which the young people come to an open clearing before the mountains, remove their suits and ties, and change into the mountain-worker apparel. They begin to throw themselves into their work. It is a scene emanating with the air of stage performance, brimming with dramatic flare. The highlight is the fact that the actors change roles before the audience’s eyes: they discard the costumes of “act one” and calmly change into the outfits of “act two” in an exposed intermission, without a curtain or screen to hide behind, and do so with a sort of abnormal calm about them. This is reminiscent of a scene in Seven Intellectuals, in which there is also a group of young men and women sitting naked atop a group of rocks. The camera lens shakes slightly, the music begins, and the youths all begin to put on pieces of clothing that have been scattered around them on the rocks. Yang Fudong himself has said it: “many things stay the same.” In “sense film,” this form that does not indulge in narrative, maybe even the artist himself has difficulty at times discerning where the starting point lies, or which camera shot of the future will be a flashback to the past.

(Translated by Katy Pinke)