Guggenheim Museum: One Hand Clapping

| August 11, 2018

Curators of contemporary Chinese art abroad often face many challenges. The third installment of the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Chinese Art Initiative, the theme of One Hand Clapping is very different from its predecessors. Whereas Tales of Our Time focuses on political territory, this current iteration zooms in on technology and its impact on society and individual subjectivity. Indeed, the initiative’s curatorial objective has been clear from the outset, that is, to radically de-center the West’s perception of contemporary Chinese art. It is especially devoted to dispelling the notion that the latter is thematically consistent, aesthetically exotic, or essentially categorizable. There has also been a tendency in recent years for Western liberal media to paint China’s scientific and technological advances in homogeneous ways, fixating almost exclusively on its quantum race, lack of data privacy, and the autocratic application of AI-enhanced surveillance systems. Thus, the aim of the show becomes double-fold: to not only present a diverse array of artistic practices from Mainland China, Hong Kong, and beyond, but also shed light on the myriad of ways that technology shapes the formation of identity and awareness of reality in a global setting.

The title of the show, One Hand Clapping, is taken from a philosophical riddle in Zen Buddhism. In asking “what is the sound of one hand clapping”, the phrase is originally invoked in 18th century Japan to contest the limits of commonplace logic and elicit enlightenment. For an aphorism whose meanings have evolved with historical shifts and cultural migration, it is unclear how artworks in the exhibition, or its overall organization, respond to the theme specifically and contextually. In keeping with the project of de-centering, “one hand” is rather employed as an abstract, open-ended metaphor to defy any fixed line of reasoning.

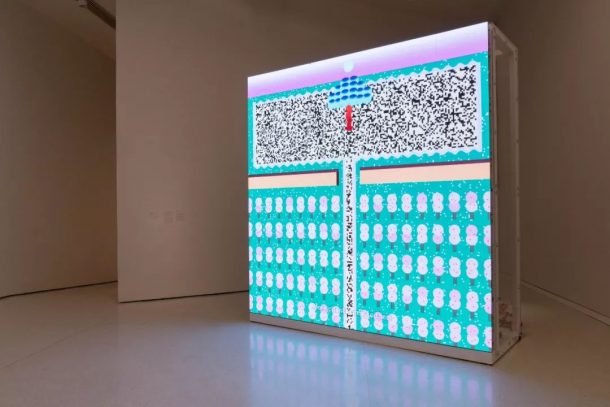

Occupying the Guggenheim Museum’s tower space, the show is divided into two floors. Hailing from Hong Kong, Wong Ping’s video installation Dear, Can I Give You A Hand (2018) dominates the fifth floor space. Composed of large LED panels, the stylized animation sequence is a perverse playground for the artist’s farfetched imagination, exploring the bitterness and absurd humor that arise from an aging population’s conflicts with an ever-consuming digital economy. Here Wong puts his acute observation skills to the test, piecing together fragments of everyday life to form an absurd tapestry. The protagonist, a retired, perpetually drooling man with only four flimsy hairs, finds himself increasingly alienated from younger generations. He laments his unreciprocated desire for his daughter-in-law, while recounting a series of digital mishaps, such as finding his priced VHS porn stash available online, or losing the password to his digital grave. The animation’s deliberately retro style—the saturated neon colors or blocky shapes—makes the explicitness of content and the harsh reality of generational conflicts much more digestible.

If Wong’s works scrutinize the technological obsolescence of the elderly from an unusual perspective, Duan Jianyu’s whimsical paintings and sculptures literally inhabit the position of the other. Her large-scale paintings of varying sizes are scattered across the space, at times looming large, at times quietly receding. Spring River in the Flower Moon Night 1 (2018) explores the ancient myth of Chang’e, who was exiled to the moon with her only companion the Jade Rabbit. Duan takes cues from Gauguin’s wild color palettes, populating her fictive landscapes with long-haired sirens, floral patterns typically found in rural areas, as well as traditional leisure times that are being wiped out by China’s rapid urbanization. Another painting depicts the flowing movements of dancer Yang Liping, who is renowned for choreographing the peacock dance, enacting what Deleuze and Guattari call the process of “becoming-animal”, or more precisely, the transgressing of borders between two distinct entities. Such a blurring of being is mirrored by groups of cast-bronze, anthropomorphic carrots. These slouched carrots, caught between the transmogrification between vegetable and human, are precariously poised between the urban and rural, mythology and reality.

Lin Yilin’s installation Monad (2018) relies on the most technical, roundabout resources to deliver a simple message. The work uses VR to simulate the singular experience of a basketball being dribbled and thrown into the air by the celebrity athlete Jeremy Lin. The artist takes inspiration from Gottfried Leibniz’s 1714 text Monadology, which surmises that the world is comprised of indivisible entities called monads that are programmed to act in a predetermined way. The dynamism of this worldview is that monads are units of immaterial force, and each individually reflect the entirety of the cosmos. Lasting less than two minutes, the duration of the VR video is too short for one to truly inhabit the energetic state of a bouncing ‘ball’, while the figure of Jeremy Lin serves as a constant distraction. Similarly, the usage of a modified drone to drop a ball into the Guggenheim’s empty rotunda in an adjacent video seems to cater to the hype of technology, than a deep inquiry into the interconnectedness of things.

On the seventh floor, Samson Young and Cao Fei’s projects are each given a separate space, providing much more immersive and contrasting viewing experiences. Young’s aesthetically-precise vision comes through in Possible Music #1 (feat. NESS & Shane Aspegren), a room painted bright turquoise, a lush aquamarine carpet, and gigantic 3D-printed objects protruding from walls and corners. Black speakers, adorned with delicately artificial flowers, are strewn across the floor, alternating between upbeat jazz and dissonant outbursts. These sounds are in fact digitally engineered, the result of Young toying with the concept of impossible instruments. While researching at a lab, he was intrigued by music archeology’s process of reconstructing ancient musical devices, particularly its fixation with reproducing authentic sounds faithful to its historical period. By radically altering parameters in given software programs, Young simulated sounds by instruments that could not possibly exist. The addition of military marching-band music subtly re-injects Hong Kong’s postcolonial history into this carefully-crafted illusory space.

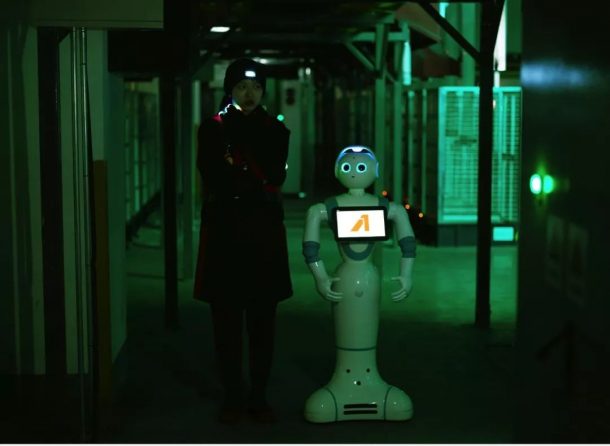

Cao Fei’s new work, Asia One (2018), drops a more somber note compared to Young’s pastel landscape. One might as well have walked into a warehouse belonging to JD.com, one of China’s largest e-commerce and logistical company. In the installation component, realism reigns, from a brightly-painted tricycle decorated with personal trinkets like family photos and Christmas lights, to a company banner with the slogan “11.11 Humans and Machines Can Create Miracles” (11.11 人机携手,共创奇迹). As in her previous works, Cao’s brilliance resides in merging broader social critique, which explores November 11, or Singles’ Day, as an artificially-created spectacle that generated record-breaking revenue for JD, and a soft, intimate touch that brings alive the otherwise dehumanized delivery workers. Asia One’s other half is a full-length movie: under the guise of a love story, it imagines the full automation of industry, juxtaposing the jarring absence of humans with stylized dances from the cultural revolution. Incredibly, the latter’s belief that human will can overcome any objective impediments to revolutionary change comes full circle in the absolute faith placed in machines.

Reoccurring throughout the show, the production of the other continues to be an urgent discourse in today’s political and technological climate. Whether the machine’s substitution of assembly-line workers, the inert object as monad, impossible instruments, mythological animals, or plight of the elderly, the marginalized nevertheless reflects our own destabilized positions and changing power dynamics. There is nothing inherently Chinese about One Hand Clapping. Its curatorial proposition proves particularly effective at evoking visual and sonic reverberations: one is tempted to imagine the image or sound of a lone hand clapping, the impossibility of which invites the viewer to inhabit a moment of silence, confusion, or unexpected resonance with materials at hand. Moreover, the artists in this exhibition are far from lone hands working away in their studios, serving more as gramophones that listen, collect and record snippets of life that are profoundly connected to an increasingly amorphous and opaque social-technological landscape.