Guo-Liang Tan: Soft Obsolescence

| August 21, 2018

©Guo-Liang Tan. Courtesy of the artist and Ota Fine Arts

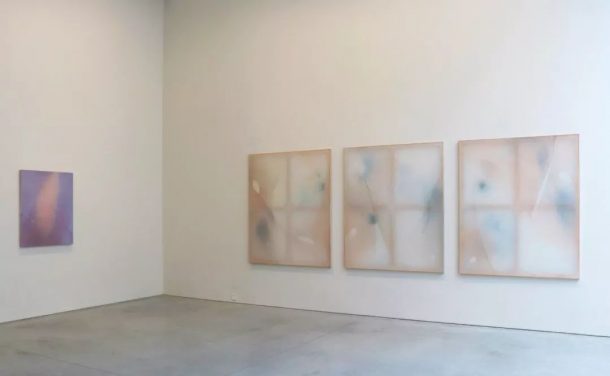

For his recent paintings, presented by Ota Fine Arts at Condo Shanghai, Singaporean painter Guo-Liang Tan chose an aeronautical fabric as his canvas. A bizarre choice, given that the fabric is water-resistant and would therefore not absorb paint. In order to even begin painting, Tan had to first seal the fabric with acrylic. In what seems like a self-thwarting move, the artist paints on a surface that rejects paint. The industrial fabric’s porosity, however, shores up a poetic futility in Tan’s recent work, which re-directs attention away from canonical permanence and onto a soft, obsolescent presence.

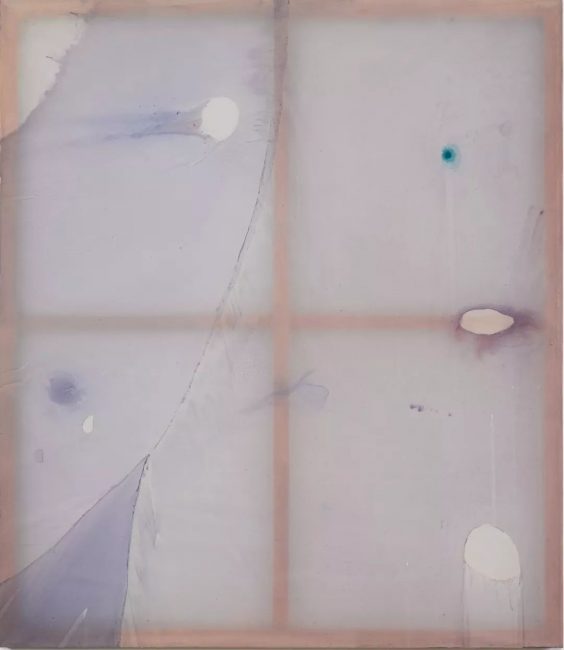

For three larger canvases, aptly titled Peripheral Ritual I, II, and III, Tan attempted to “accentuate [the] ephemerality” of his prior series of paintings, Ghost Screen, which echoes the formal and conceptual concerns of these new paintings.[i] Spectrality is clearly on Tan’s mind. He started making these new paintings by literally circling the peripheries of the horizontally laid out canvases, working on their margins first and intentionally avoiding the cores, leaving them noticeably pale and absent.

©Guo-Liang Tan. Courtesy of the artist and Ota Fine Arts

Washed in amorphous skin-pink hues, the translucent surfaces of Peripheral Rituals suggest a bodily presence that is sparse, threadbare. For these paintings, Tan experimented with numerous techniques and temporalities to create stains of differing effects. Bruises in deepening shades of blue ornament the canvases’ corners. Where paint has soaked in luxuriously here, in other parts, it appears to have been flicked on rapidly in a duller greyish hue. Elsewhere, lavender is scratched ever so lightly onto the canvas.

More prominently in Ghost Screen, acrylic glides vertically, horizontally, and obliquely, signaling the artist’s tilting of the canvas. Color is made through time and space. This palette of chromatic textures and viscosities hovers above a visible, naked frame: ethereal meat to the skeletal context of painting. Surface and support intricately embrace in the artist’s evanescent web.

©Guo-Liang Tan. Courtesy of the artist and Ota Fine Arts

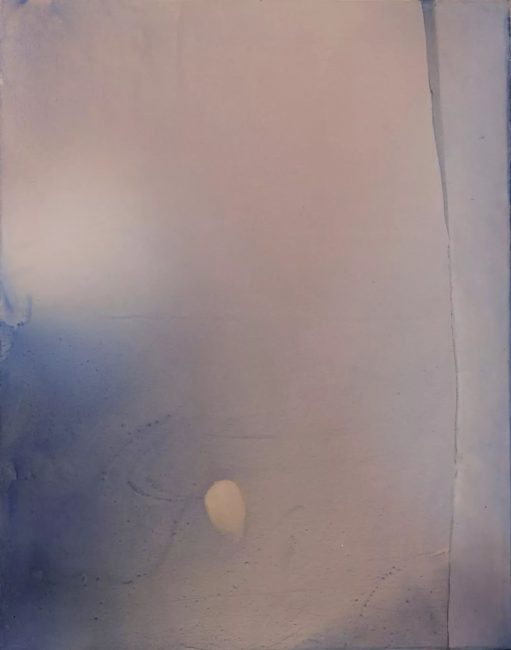

Two smaller paintings, Navel Glaze and Untitled (Shaft), exude a resonant shadowy tenor. In these works, chromatic gradients of purple-pink and blue-orange were created by fitting a smaller painting in one color behind a larger one in the other, another technique that Tan used in Ghost Screen. Their airy, seamless illusions an intimate consequence of the artist’s doing.

Photograph by Wong Jing Wei

©Guo-Liang Tan. Courtesy of the artist and Ota Fine Arts

Even the absences on the canvases captivate. To create leaf-like segments of white, reminiscent of those on Untitled (Cassiopeia) and Violet Faults from his Ghost Screen series, Tan intentionally halted the flow of his paint with rubber and Arabic gum. This impedimentary act paradoxically produces more gestural effects.

Rubber generates clean lines of exclusion, clinically delineating the spaces that paint has touched the canvas. In these instances, paint holds on and stains even more stubbornly around the moulds that curb its mobility. Undeterred, it leaks more uncontrollably and deepens its intensity on the canvas. Arabic gum produces rougher, more indistinct boundaries where paint appears to amalgamate, terrace, and crust around its obstacle. The artist’s austere proscriptions and regulations yield infinitely unknowable permutations. The resulting bone-white elliptical shapes, untouched by color to varying degrees, make Tan’s canvases appear even more gossamer.

Photograph by Wong Jing Wei

©Guo-Liang Tan. Courtesy of the artist and Ota Fine Arts

Together, Tan’s paintings are certainly gestural, but in a transient, haunting manner, rather unlike what Briony Fer calls the “expressive liquidity” of the canonical chauvinists of Western art history.[ii] In contrast to the masturbatory grandiosity of the latter, Tan’s paintings have a near-mute presence – pensively silent on the sensorial periphery and anchored in prosaic rituals and experimentations of making.

When artist Eva Hesse asked herself “How to make by not making?”, she answered with an equally esoteric axiom: “It’s all in that/ it’s not new. It’s what is not yet known, thought seen touched,” her final neologistic phrase hinting at the intangible, affective feel in her work. Writing about the emptiness so central to Hesse’s work, Fer ruminates that “it’s all in the future, [for] after all, making is making what has not yet been made.” There are certain kindred qualities to glean here in relation to Tan’s paintings, in particular, their nullifying yet elegiacally generative potential. By deterritorializing the act and object of painting (avoiding its center, tilting it, laying it flat on the ground, circling it like a vulture) and saturating its surface with all manner of stains, hollows, and washes, Tan gently and thoughtfully continues the slow work of repurposing the legacy of a genre.

[i] Correspondence with the artist.

[ii] Briony Fer. The Infinite Line: Re-making Art after Modernism. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004.