Musquiqui Chihying: “I’ll Be Back”

| 2018年10月31日

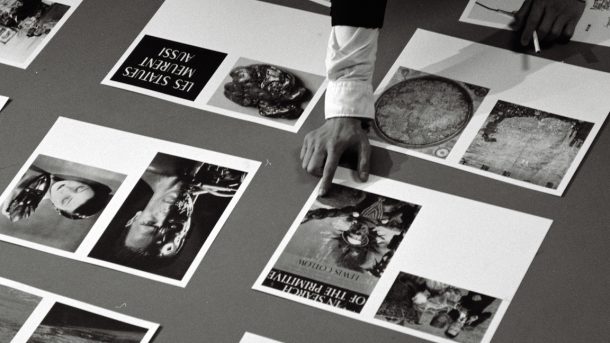

There is a powerful image at the core of Musquiqui Chihying’s “I’ll Be Back.” In The Sculpture (2018), presented as both a double-channel video and print, the artist poses in emulation of an iconic 1954 photograph of French writer and politician André Malraux, where he is pictured nonchalantly smoking, with proofs for an upcoming book arranged on the floor around him. A cigarette in his mouth and hair swept to the side in imitation of Malraux’s detached Gallic cool, Chihying sorts through his research materials for the project at hand—an investigation and re-imagining of Sino-African relations.

The choice of Malraux as a model is significant. He was a Leftist intellectual who also stole artifacts from Angkor Wat—as a public figure at a time when overt colonialism was being dismantled, he represents better intentions than the pure Orientalism of the past, yet also cannot be considered an entirely positive figure. In an era where geopolitics is being renegotiated, Chihying asks if new relationships are really a break with the past, or if—as personified by Malraux—there are still uncomfortable continuities and tendencies.

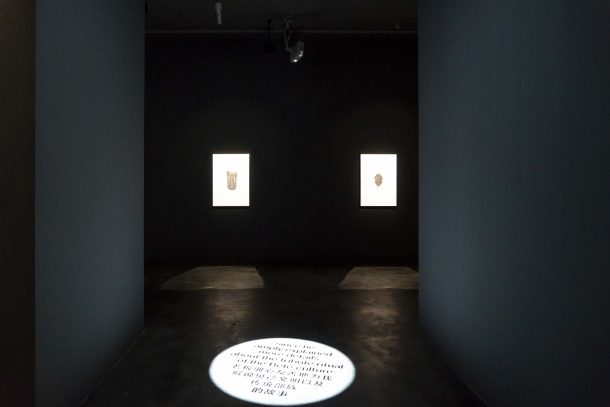

As a Berlin-based Taiwanese artist, Chihying’s work has dealt with the legacy of colonialism through a variety of means, from humorous videos such as Jog (2014) reflecting on his position as an Asian artist in Europe, to Sound Route: Song of SPECX (2016), a music research collaboration with Wu Chi-Yu and Shen Sum-Sum examining links between Dutch colonization in Indonesia and Taiwan. Some of the themes covered resurface in “I’ll Be Back,” albeit with a more somber tone, a mood heightened by the exhibition’s presentation in a darkened room, most of the non-video pieces only visible through strategic spotlights.

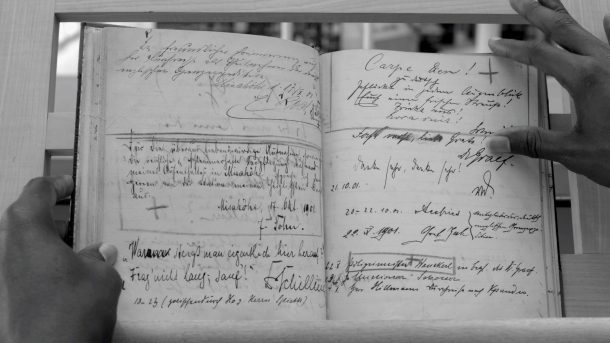

The figure of the (post-) colonial subject as sojourner resurfaces in The Guestbook (2018), a video following Do Do, a Togolese actor, walking through Berlin. He encounters hallucinatory traces of the 1896 German Colonial Exhibition, reads documentation of the German colonization of his home country at the Berlin State Library, and follow clues to the site of “Nanking,” a Chinese restaurant which Chinese statesmen Zhou Enlai frequented when he lived in Berlin in the 1920s. However, the restaurant is long defunct, replaced with a bubble tea café/massage parlor. Talking to the owner, Do Do realizes he is decades too late to meet Zhou, and opts for cupping treatment instead. Filming with an entirely non-white cast, Chihying touches upon the rarely represented multicultural character of Berlin, and poses questions about anti-colonial solidarity. Did Zhou encounter African peers in Berlin, and what impact would they have had on his thinking? What has been left unresolved since he helped bring African states closer to China in the 1950s and 60s?

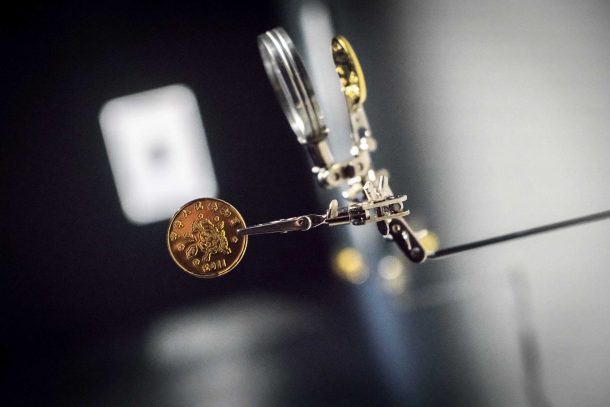

Other pieces are tied to traditional arts but more focused on the present moment, as China has become a source for investment in Africa in manner different from the anti-imperialist development projects of the previous era. For The Cultural Center (2018), Chihying created commemorative coins for Chinese-built cultural institutions (theaters, museums, etc.) in Africa. The Mask uses sketches, video projections of text, and a sound recording to let an art dealer from Côte d’Ivoire explain the story of five Ivoirian masks now in the possession of the National Museum of China. Letting the dealer speak on behalf of his country’s artifacts restores a sense of agency lost in their collection by a foreign institution. But it also remains ambiguous whether the dealer’s words, read out in Mandarin by an African student based in Beijing, are true or not. Chihying leaves the viewer questioning if both sides see eye-to-eye or are operating on the same level in these cultural and commercial exchanges.

Video elements of The Sculpture address European treatment of illegally acquired African artifacts, and introduce Xie Yanshen, a prolific collector of African art who has provided the National Museum with much of its African holdings. Implicitly, it asks if the privilege to collect and categorize can be separated from power, or if it shall always imply a hierarchical relationship, as evocatively staged in the portrait of Chihying-Malraux. Reexamining the image, the exhibition’s English title may gain new resonance: incongruously, a picture of a Terminator robot from the eponymous Arnold Schwarzenegger-starring movie series (catchphrase: “I’ll be back”) peers out next to the artist. The Terminator’s near-indestructible skeleton contains coltan, a rare metal, which it should come to no surprise, is predominately found in Africa and is used in mobile phones. Undertaken legally, the collection of African arts and crafts might be a comparatively innocuous pursuit, but it can’t be divorced from the pursuit of more valuable resources and the larger forces of power at play.