Devices of Decolonization—A Conversation with Cuauhtémoc Medina

| June 28, 2019

Rather than planning an exhibition, the curator Cuauhtémoc Medina’s approach towards the 12th Shanghai Biennale is more like choreographing disparate relationships, between the ancient times and the present, and between the ancient thought from East Asia and the Mayan Popol Vuh from Latin America. In this conversation, writer Zian Chen discusses with Medina the complex web of references in his curatorial and research work.

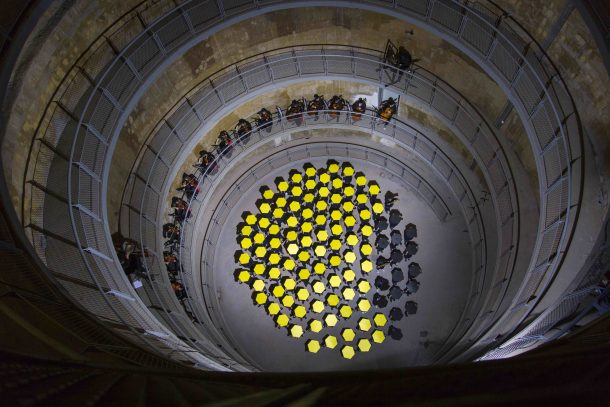

HD video of performance with sound, 15 min

Installation view at “Proregress”—the 12th Shanghai Biennale, Power Station of Art, Shanghai, 2018

LEAP: Could you briefly outline a defining feature of this Shanghai Biennale and its response to denaturalization?

Cuauhtémoc Medina: This exhibition actually starts from an attempt to delineate the precise means for knowing or suggesting elements of time and space. So here the artworks are to be approached like instruments and oracles. Even the title of the exhibition is an artwork, a poetic artifact, directed towards a certain purpose.

LEAP: This ambivalence might be captured best in Hsu Chia-Wei’s Black and White – Malayan Tapir. In the film one can see a benevolent intent to decolonize nature. But the narration is delivered by a tour guide in a zoo, whose strident tone, full of professionalism, reminds one of the contextual framework of Western naturalist and global tourist legacies. It seems that there exists no stable linguistic ground for environmental writings to differentiate themselves from anthropocentrism.

4-channel video installation, 6 min 55 sec

Installation view at “Proregress”—the 12th Shanghai Biennale, Power Station of Art, Shanghai, 2018

CM: I have to start by bowing to Hsu Chia-Wei, as he brilliantly noticed that in diplomatic and international activities there exists a significant and primitive fetish of black and white animals – not only the Malayan tapir but also the Chinese panda. This tells us that symbolism is enacted on a level less secondary than we had pretended. To go back to your initial question: There’s the notion called slippage of senses, which posits that sometimes there’s a change in symbols for certain meanings, and vice versa. I think what we addressed as ecology has to do with our awareness of its signification of contained unity and conflict. Based on that, there’s also the awareness of catastrophic disruption coming from economic practices and social development, in the face of which other natural systems are obliged to cope or adjust. It is this understanding that there’s a set of connections, a complexity that is in the basis of what we are trying to develop when we raise the question of ecology. I recently came across historian Andrea Wulf’s book, The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World. In it, the early nineteenth century German explorer and philosopher appears as the first to notice the ways in which land exploitation and mining would affect the fate of jungles through his travel to South America. The book is about the interconnectedness between different natural ecosystems a great distance from one another. Later in his life Humboldt reinvented the notion of cosmos as a way to summarize such interactions, stating: “it was the discovery of America that planted the seed of the Cosmos.” This point brings us back to our project here. It’s about the thinking and handling of the world and the lack of vision for how things are related. This is an exhibition against simplicity, and the danger of simple mindedness. So to put it clearly: we try to prevent our interaction with nature from becoming a natural concern. There’s a need and obligation to get rid of the ontological barrier that modernity has erected.

LEAP: I appreciate the character of the exhibition, wherein artworks are seen as devices. A number of speculative works adapt vernacular or historical modes of speculation; for example, the moon calendar is suggested as an ordering device. But sometimes it’s hard to fathom where these forms of nature writing narrative, presented in the format of contemporary art exhibitions, would eventually or eventfully lead to.

Photographic installation, 128 panels, 28.5×18.5 cm each

Installation view at “Proregress”—the 12th Shanghai Biennale, Power Station of Art, Shanghai, 2018

CM: I am compelled to quote Humboldt’s warning that when thinking of nature, we are sometimes afflicted by a certain escapism, or the hope that there might be reality beyond civilization. Here I would add that such escapism usually projects our resignation, and enters into a non-human, beautiful machine fantasy. What is important, for example in Pablo Vargas Lugo’s “Eclipses” series, could be to understand the question of truth (the eclipse is a prediction in the long-term that can be faithfully trusted) in the intersection between the form of political formations addressed by the use of mosaic, and the awe that we express in the face of natural orders. I feel you might also be alluding to Leandro Katz’s The Sky Fell Twice. The titular sentence originates from the ancient Mayan poem of Popol Vuh, and Katz follows that culture’s understanding of the sky as a categorical order, a perspective not so far from the Chinese view that rule and justice comes from above. It is a kind of perspectivist thinking. And so he created a lunar alphabet based on photographs from the moon cycle. Our curatorial team is interested in the complex textures of connectedness, and the works in the biennial are bound by this common preoccupation. It’s even a sort of pride in connectedness, eschewing the affixing of meaning through identity and otherness. Similarly, the view of a parrot in Allora and Calzadilla’s The Great Silence presents a moment of awe. It invokes the question of how we connect two different species, which is not so far from the issue of contact with interstellar beings. You can also find such an effect in the adjacent works by Amalia Pica and Rafael Ortega about the Great Ape divide.

3-channel HD video, 16 min 32 sec

LEAP: There are many artists who frame their subject matter from a discrete point of view, then pull its strain into to a larger, sometimes even cosmological scale. How would you further express this “pro-regress” practice of moving backward and forward at the same time?

CM: This is an interesting paradox that is not unique to my exhibition. It would seem, at the moment, that rather than make generalizations and produce abstract perspectives, it’s more fruitful to think within, and enter into trust with, the significance of the particular within wider perspectives. This comes down to the seeming paradox that most of the works that we are now displaying have to do with very detailed, localist investigations, and very particularist connections that never pretend to reach universal or logical conclusions. It’s like you are making connections of synecdoche (sorry for using a term from classical Western rhetoric), rather than symbols or metaphors, in which there are fragments speaking about the whole, without being a whole.

There have also been significant efforts toward investigative aesthetics, with Forensic Architecture and other disciplines questioning the knowledge divide between sensible approaches of practice in the cultural world and the most rigorous data management. So there’s this sense that we have a number of practices putting into use a complex sensibility, also according proper epistemological significance for knowledges formerly seen as enemy categories.

And finally, we are in a situation wherein there are events trying to transmit from significant locations, not arguments, not artworks, but situations. And these are what we call biennials. I don’t see them as sites of recipients and representations, but the sites of connections. These circumstances attract those artistic projects that are trying to work on knowledge-based practices of a different kind, without anthologizing, ethnologizing, or even ideologizing the subjects.

Videos and printed diagrams

Installation view at “Proregress”—the 12th Shanghai Biennale, Power Station of Art, Shanghai, 2018

LEAP: Yes, there’s a general feeling of the show operating on a set of double affirmations: between knowledge and sensing, between universal and particular, between a general future and one’s otherness.

CM: Just as we can ask oracles what has happened, we can also ask Western science fiction about the future, as well as one’s otherness. For example, the narrative of Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days could be instrumental in explicating, quite presciently, the issues of developing transatlantic global markets. Also, we can say that Blade Runner is about the humanity of the lifelike human replicants, with the key testimony from replicant Roy Batty basically amounting to the slave telling the master that “my humanity created by your oppression is a renewed humanity.” But likewise, if you read Blade Runner in line with what has happened, then you find yourself dealing with the stories of immigration, and of the global north/south division.

So what is this manifesting to us? Science fiction is distinctive for allowing you distance from your historical and social conditions. And one always has to be aware, that science fiction as a genre comes from a specific origin of utopia and travel writing, triggered when witnessing the multiplicity of the world. So one may say the notion of science in the genre title is a misnomer. The element of drama here is that of exponential loss. This context becomes expressively reflective, for example, in the Blade Runner scenes in Deckard’s apartment. I literally saw its interior as a Mayan temple. It’s that moment of revelation that “my ancestry is involved in this movie”.

LEAP: In terms of dealing with one’s objecthood in the master’s dreamscape, and further disturbing it, I feel that there is a nuance between the two different modalities in Afro and Asian Futurisms: the Afro Futurist mode of narration follows an essentially revolutionary narrative of racial struggle, whereas the Asian one seems to delve into a willing self-alienation (Lawrence Lek’s Sinofuturism is one example). Can you share with us more about the case of Latin America, and how it would figure into this broader picture?

CM: Latin American thoughts on the future have to do with the way in which elites operate in the region’s mass culture, for example in the negation of Catholicism. My book Olinka: Dr. Atl’s Ideal City, just published today back in Mexico, takes Gerardo Cornado as its subject matter, a Mexican painter and writer who signed his works “Dr. Atl.” His goal was, brutally summarized, to kill god. Here, in at least one strain of Latin America’s science fiction and extraterrestrial thinking, we see a thinking beyond Catholicism, of deploying forms of transcendence that would break dramatically from colonial logic and the Catholic church. This ethos is sexually, politically, and religiously indebted, and Dr. Atl is just one example of it. But what I try to argue is that some of these thoughts have less to do with the questions of social representation, which is the question for the futurists that you are drawing.

Another extreme and mad example: in the mid-twentieth century, one of the major leaders among Argentinean Trotskyists was Juan Posadas, who developed an ideological theory about witnessing highly developed interstellar craft. As their mode of production has become more advanced, he thought, a possible way to revolution would be to align with the alien forces and impose communism on earth. Through Posadism, I’m sure Latin America has authored some of the weirdest chapters in the history of communism, rendering Asian communism lame and Soviet cosmic ideas mediocre.

LEAP: How did you collaborate with the three co-curators?

CM: I work with the three co-curators I appointed, and each of us is responsible for a segment with a certain consistency with the shared questions, which in the beginning was quite straightforwardly about the ambivalence of values.

There’s one section crafted by Wang Weiwei revolving around the question of emancipation and control, and of how social order is managed, understanding that these are not any longer contradictory notions. On the basis of this polarity, Wang also raises the question of the social body, asking how it is that a certain stricture, a certain notion of tradition, and certain transmissions of norms conspire in shaping the social body. María Belén Sáez de Ibarra has been working on the cosmopolitical concept of the jungle by looking into what contemporary culture might have to do with the Amazonian rainforest. I’ve invited her to develop a project on that basis. Yukie Kamiya started with the concept of the blurring of peace and war, conflict and harmony. I myself look into the question of how it is that a cultural practice is constantly reframed to its other, how it’s always contaminated by other disciplines, and how culture is barbaric in certain ways.

After we made decisions on themes, we then come up with a series of corridors where our individual thinking would converge into specific issues, on which there are written reflections operated like epigraphs that you could read as you walk. And on purpose, we had a couple of exchanges between different sections, so as to blur their boundaries, generating a kind of nebula. What’s good about a nebula is that you don’t see specific stars but rather everything together as a cloud.

LEAP: There have been quite a few biennials (China not excluded) addressing the topics of technological and ecological fantasy. What do you think about these keywords becoming part of the metabolism of biennials?

CM: I think there are certain advantages that some people in the art world confer upon biennials. The concern of biennials should not be about how we now pass through a phase of fixating on one theme, be it colonialism or climate issues, and then jump onto another agenda. The metamorphosis of biennials means they are no longer simply about the promotion and insertion of global dialogues, and this has forced institutions to look for other reasons of resistance, resulted in the versatility of exhibition models currently operating, with further complication of thematic concerns. So to see that some people are still carrying out the goals of the biennials from the 90s is depressing. At times I’ve even heard them boast about the present situation as a mannerist moment, with simply too many exhibitions to track down. Such sentiment, I would argue, is actually a nostalgic trap, as if they were living in the time when hopping between European cities was not a function of privilege, but rather a professional fashion.