Northeast China, A Slippage—a Conversation with Ban Yu

| July 10, 2020

Northeast China has always provided an important lens through which to observe modern-day China. Its landscape holds memories of modern warfare, the birth of the nation’s heavy industries, and the reclamation of frontier wastelands. Then, following the abrupt erosion of the socialist-era philosophy that “the working class must lead in everything,” and the dawn of “reform and opening up”, this place, which Mao Zedong once referred to as the “eldest son of the People’s Republic of China”, suffered a political and economic decline. Entering into the new millennium, nevertheless, it reappeared in the public view showing an absurd yet entertaining image.

Courtesy the artist and Magician Space

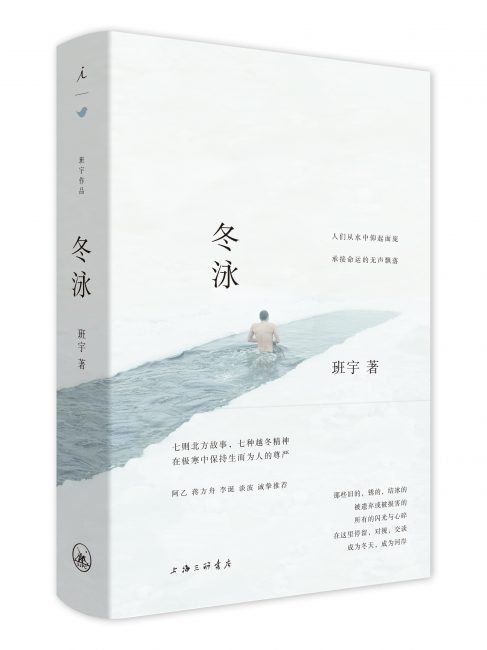

Twenty years after master documentary-maker Wang Bing took up his camera to record this scenario in the 551-minute West of the Tracks (Tiexi Qu, 2002), Ban Yu, a writer born during the 1980s in Tiexi Qu, Shenyang, unveiled his debut short-story collection Winter Swimming (2019), which tells the tale of how the average Joes and plain Janes living in worker’s villages try to maintain the last remnants of romance and dignity in the context of their otherwise banal lives. The signature “tones” that are particular to the dialects of northeast China infuse Ban’s work, giving it a distinctly regional quality that has led some critics to equate Winter Swimming with Jin Yucheng’s award-winning Blossoms (2015), one of the few novels to have been written in Shanghainese. Ban’s personal style is more pronounced, however, in the way in which he delivers information—his sentences are short yet powerful, his narratives are direct and colloquial, his dialogues written in a phonetic manner that makes you feel as if you are really there. All of these have enabled Ban’s depiction of the vicissitudes of life in northeast China to achieve a wide resonance among Chinese readers today.

The northeast is all too frequently portrayed as an area of economic ruin, rampant crime, and a decadent scrabble to live. Media and popular representations of the region are often abrasive and flattened. It’s a stereotype with which Ban dissents. In the seven stories that make up Winter Swimming, the northeast is full of complicated tensions, a place where indescribable sentiments grow on the lengthy winter days. Its people educate themselves through reading, painting, and music, and its cultural soil may prove fertile for new possibilities for the future.

Oil on canvas, 304 × 340 cm

Courtesy the artist and Vanguard Gallery

Zhao Mengsha: In today’s world, it seems more appropriate than ever to talk about regionalism. Continents are turning into islands, political camps are divided, and nationalism is fermenting. When you look at the paintings that characterize the early stages of contemporary Chinese art, regionalism used to be a popular theme. At that time, artists were trying to find their own ways of integrating ideas drawn from the outside world, and from the western artworld in particular. While it is widely recognized that the “85 Art New Wave” marked the beginning of the contemporary Chinese art history, a number of artists from northeast China, including Shu Qun, Wang Guangyi and Ren Jian, came together as “the Northern Art Group.” They worked to offer a cultural interpretation of northern civilization with a focus on the “permafrost spirit:” a blend of rationality and the sublime. Northeast China does boast expansive permafrost at high latitudes, and its distinct geography nurtures a special cultural atmosphere. I am wondering, historically speaking, is there any parallel or connection between the explorations of “regionalism” in literature and contemporary art?

Courtesy the artist and Magician Space

Ban Yu: What you just mentioned is really intriguing. If we regard “85 Art New Wave” as the initial phase in the contemporary Chinese art history, then the development of contemporary Chinese art is almost parallel with that of domestic literature. Specifically, I think the history of northeastern Chinese literature has at least three key phases. The first is shaped by Xiao Jun, Xiao Hong and Duanmu Hongliang as the first-generation writers. They put great emphasis on “northeast China” as a concept. For example, most of Xiao Hong’s works were set there. Chi Zijian was the pioneer of the second phase. She took northeast China as a broad, humanist space in which northerners’ stories unfold. She would infuse her works with the crystal and magnificent natural beauty typical of the land, hence the prevalent elements of naturalism. There is, for instance, a very fine paragraph of descriptions in The Last Quarter of the Moon (2005). In that excerpt, the perspective of a man suddenly changes into that of a deer running on ice. I think this is a notable creation and contribution. Now, in the third phase, the works by myself, as well as by fellow writers Shuang Xuetao and Zheng Zhi, all explore reflections on northeast China during the 1990s to the 2000s. That’s why we are often referred to as “the northeastern writers.”

ZM: Why do you all write about the past of northeast China, especially about workers laid-off during the period of industrial decline? And why is that particularly resonant today?

BY: If it were an on-going trauma, like the current COVID-19 pandemic, grappling with the situation would be hard enough to live through, let alone write about. How could you effectively sort out the multitude of information? You would even struggle to identify a personal perspective through which to analyze the bigger event. When it comes to the mass layoffs during the 1990s, it is only now that we’ve gone through the process of economic restructuring that we can look back and reflect on the trauma people might have experienced. I think literature is always closely related to the development of a specific region. In northeast China, this relationship is the product of politicals in one aspect, and geographical environment factors in the other. The descriptions of Xiao Hong and other first-generation writers highlight for us a reform period, and those of Chi Zijian reveal the influence of Modernism. Myself, Shuang Xuetao, Zheng Zhi and other writers are considered “post-avant-garde writers.” This is to say that, our writing skills and styles are in fact very much influenced by Modernist writers. However, this kind of influence is a secondary one. Instead of drawing upon foreign writers directly, we are mostly influenced by Ge Fei, Ma Yuan, Yu Hua, and Su Tong—the first wave of Chinese writers to integrate modernist writing styles. As you mentioned earlier, their experience represents a blending of Modernist ideas with regional philosophy. What we drew upon is the outcome of that integration. But beyond that, it is essential to find a way of telling good stories that suits ourselves.

ZM: “Northeast China Studies” has already become the object of academic study. In 2019, you attended a forum on the subject as a representative of contemporary literary circles.

BY: Yes. The forum was moderated by Professor David Der-wei Wang from Harvard University, an expert in Chinese literary studies overseas. It took the form of a roundtable. Ten scholars dedicated to different fields were invited on the occasion, including those who study the phonology of northeastern Chinese dialects, literature in the Manchukuo period (Japanese, Chinese and North Koreans), as well as literature in the Chuang Guandong period (a hundred-year period beginning in the last half of the 19th century when the Han Chinese rushed into Inner Manchuria to make a living). Wang is originally from Taiwan, and he believes the history of northeast China is very similar to that of his homeland, as both regions have experienced a colonial period and both provide a home to multiple nationalities.

ZM: Once dubbed “the eldest son of the Republic of China,” the northeast was once rather advanced in terms of urban construction.

BY: Urbanization in the region started very early. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, Shenyang was already a modern city. Yet the shift and transformation happened very fast—the whole cycle of its rise and fall has taken place within just three decades.

ZM: From a land where the working people could build a new world with their hands to one of the country’s economic tail-enders today, why does northeast China, as depicted in rustic internet videos, films or literature, often greet people with a dramatic image?

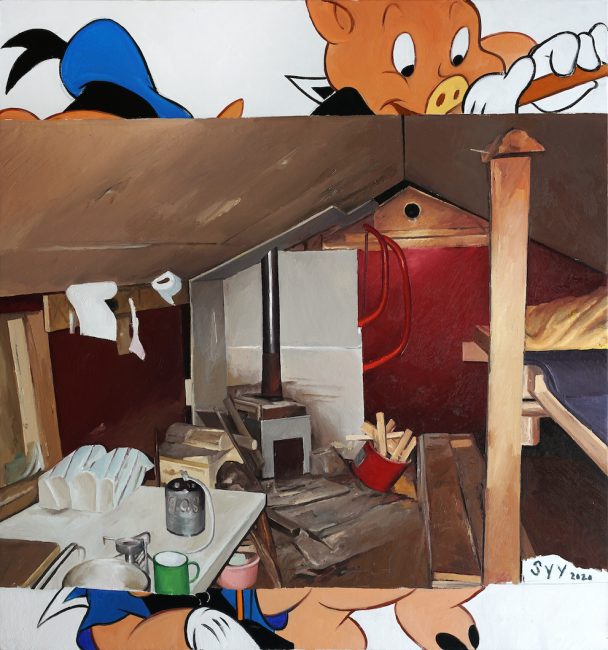

BY: It seems to me that the media tends to mold northeast China into a cartoonish image. If you meet a person from northeast China, you’re conditioned to think that they are immediately going to say “What cha lookin’ at?” or that the “gold” necklace they wear will float if you toss it into a pond. But, as in Tom and Jerry, the mouse always beats the cat. I believe that northeasterners may have a strong desire to perform at certain moments: they display such a personality on purpose so as to satisfy their emotional needs and catch attention. The flipside is that, in northeastern literature, you can easily imagine what the characters are like, and thus easily get into their context and perspective.

Oil on canvas, 130 x 140 cm

Courtesy the artist and Vanguard Gallery

ZM: Why does northeastern Chinese literature manifest that kind of collective identity today, while other regions don’t stand out? Ban Yu, Shuang Xuetao and Zheng Zhi, three contemporary Shenyang natives, wrote about the 1990s and became a focus of attention almost simultaneously. Why them, not others?

BY: In my view, though our narratives are about the past of northeast China, the experience is certainly not limited to this land. The wave of mass layoffs in the early 2000s swept across the country. When people in Shenyang were sacked, jobs in Wuhan, Changsha, etc. were cut as well—but the layoffs in northeast China were on a grander scale and often given more attention.

120 photographs

Courtesy the artist and Magician Space

ZM: Indeed, the change of social structure had a particularly notable influence on the generation of our parents, who grew up eating communally from the same kitchen in factories. They often miss the secure and simple life under the planned economy, a system that relied on a doctrine in which the State would feed them as long as they worked. As a result, many could not overcome the psychological blow dealt by their being laid off. Is it this resonance with the past that spawned the so-called wave of “Northeast China Renaissance”?

BY: This term was originally coined by the rapper Baoshi Gem. We’ve personally experienced those days, and learned about certain ways of narration, so we are able to illustrate the era. I don’t understand why many dub northeast China a uniquely fertile soil for creation. I consider this to be something molded by artists and writers retrospectively. In actual fact, whether it be songs written by Baoshi Gem, short videos shot by Laosi or novels complied by myself, they are centered more on humanity than the specific geographic area. That’s why we tend to relate to Laosi’s videos by thinking “my mother is like that too:” there is something universal in the works coming out of the northeast.

120 photographs

Courtesy the artist and Magician Space

ZM: Then what is so particular about the literature and art from northeast China?

BY: I think that, the region used to be a hub of cultural consumption, at least, during the 1990s. For instance, our parents’ life routines each month were arranged quite properly. They worked in factories and got a monthly salary of 800 yuan. The pay slip would indicate various kinds of items: a reading fee—five yuan would be allocated to reading books and newspaper each month—for example, or ten yuan for bathing and hairdressing. Back in the day, northeastern Chinese people loved dancing, and many young people played musical instruments like guitar. That was their way of recreation and entertainment, which makes me feel that our parents were actually artier and more bohemian than us. It impressed me that, back when I was a kid, every family would go to the factory library to borrow books, even if they were mostly romance and kung-fu novels. That might be a process of affecting each other, a legacy passed down to raise our consciousness of spiritual seeking, which you might say is a mindset of urbanized populations.

ZM: Is it a feature of workers or the working class?

BY: The working class in the northeast is a well-programmed class, or at least it’s supposed to be. Compared to farmers painstakingly toiling in the fields, workers need not worry about the weather. With a relatively established policy in place, we can live a relatively stable life. Your personal life is supported by an integrated welfare system as well as remuneration so as to ensure the free growth of your own personality outside the eight-hour working day. The design of the whole system leaves you space to develop hobbies and lead an arty life. In his 1981 book Proletarian Nights, Jacques Rancière also shed light on the life of workers—via nineteenth-century experiments in writing poems and essays together.

ZM: Just now you noted that we often cast the northeast in a cartoonish fashion, or as a stereotype highlighted in comedy sketches. But in Winter Swimming, I also came across characters who are unable to buck the era of decline, just like those in the popular movies The Piano in a Factory (2010) and Black Coal, Thin Ice (2014). A sweeping sense of defeatism imbues the depiction of the northeast in all these works.

BY: I don’t think about what readers may feel when I’m writing, or what era-specific features this is all about; instead, I focus on narratives and characters. Such sentiments may give rise to stereotypes of northeastern Chinese literature and mean that the stereotypes can hardly change. In fact, we are trying to represent something bigger. But it may be easier for many to approach and comprehend our work from the perspective of geographic and regional environments, which solidifies their perspectives.

For me, a work starts with a single sentiment that cannot be articulated. You need to try your best to describe it clearly through the form of the novel, rather than simply generalizing it into words like sorrow and pain, or joy and pleasure. A person can be happy and at the same time vexed. You may have a lot of inexplicable emotions in northeast China, and the dichotomy between a person’s happiness and unhappiness or between right and wrong does not hold here. I believe that all novels and artworks need to, at least for me, explore such an ambiguous space. Whether it be writing novels or making paintings, ultimately they need to be a reflection of a person’s selfhood. Different people say different things. And in your own works, you just cannot lie.

Film, 1 hr 39 min

Courtesy Geng Jun

ZM: Reading your fiction is sometimes akin to reading on a screen for me. There are many dialogues and short sentences, which produces a sense of speed.

BY: I think good novels need efficiency. The short sentences, as well as all my narratives, are the result of external projection, rather than something philosophical, like the endless self-reflection of Thomas Mann. I’m writing to tell you about an event, a behavior, a person or a dialogue, not the various thoughts tangling in my head. Mann’s way of writing is in fact very difficult to pull off, and most contemporary Chinese writers cannot reach his level of reflection or speculation in my opinion. So it’s better for me never to start doing so. Efficient communication cannot be achieved by any deliberate narrative strategy; instead, there must be slippages and room for poetry in the language.

Film, 1 hr 39 min

Courtesy Geng Jun

Zhao Mengsha is an editor, art writer, and co-founder of abC Art Book Fair.

Ban Yu, born 1986 in Shenyang, is a fiction writer, and author of Winter Swimming (2018) and Wandering at Ease (2020).