A Show About Nothing

| October 8, 2022

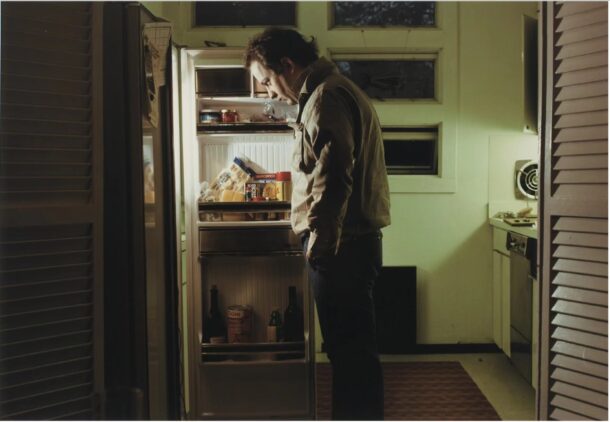

It is late April in Shanghai; any “normalcy” has spiraled into abstraction, owing to its protracted absence from life’s routines. My daily existence consists of humdrum cycles of hunger, sleep, and emotional exhaustion; think Philip-Lorca di Corcia’s Mario (1978), where a lone man stares glumly into an open refrigerator. The stocked cans, cheese and bottled wines appear stale, much like the lethargic state of his sluggish chin. He stands expressionless—no hunger or desire—as emptiness shrouds the coldly lit kitchen.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Mario, 1978, chromogenic print, 50.8 x 61 cm. Courtesy the artist

No one could have predicted that, in the months that followed, this modestly sized photograph—hung in a corner on the second floor of “A Show About Nothing” at Hangzhou’s By Art Matters—would reference as a footnote to the impending enforcement of zero-COVID policy, alongside other rippling effects of a system that employs a forceful “mobilizational governance” logic [1]. In light of current circumstances, “nothingness” has been supplanted in the exhibition’s discursive and aesthetic context by a quantitative definition of “zero(null).” Ironically, the substantial decline, mortality, deletion, and loss that knock the term from its philosophical plateau are also a salutary demonstration of its conceptual malleability.

A Show About Nothing, proposed by Francesco Bonami and curated by Stefano Collicelli Cagol, Wu Tian, and Sun Man, is the inaugural exhibition at By Art Matters, a new contemporary art museum in Hangzhou whose versatility as a space permits the showcasing of richly diverse works. The greater challenge lies in getting these works, including those not part of the museum’s permanent collection, to respond to the exhibition’s thematic concept of “nothingness.” Much akin to John Cage’s composition 4’33” (1952), which is experienced through an inactive onstage performer, each work is somewhat waiting for a “nothingness” to underscore its presence along the show’s conceptual axis. Furthermore, with a curatorial structure that strives for a democratic openness (perhaps even slightly, out of focus) to the concept’s interpretation, the exhibition’s effectiveness is deeply rooted in the number of successful markings “nothingness” has procured from the works on display.

展览现场-610x457.jpg)

“A Show About Nothing”, installation view, By Art Matters, Hangzhou, 2021-2022

At intervals, the gallery bursts out with gallery staff chanting, in English, “Oh… this is so contemporary”—a restaging of Tino Sehgal’s live performance This is so contemporary, which premiered at the 2005 Venice Biennale. There is no tangible trace to this recital beyond the echo of its final words. I tried to get a close-up view of the participating staff’s expressions, but nothing surfaced; sadly this performance didn’t seem to elicit the engaged experience that might have been hoped for. It did, however, remind me of a pun on my social media chat log: “挺当代的(very contemporary)” in aerial black. It is witty, frustrating, and downright applicable to almost everything. It describes every second of our contemporary lives, where no matter how absurd our reality is everything can be instantly wiped away, forgotten. Which explains why Sehgal’s piece remains relevant: “tracelessness” is so contemporary.

Located on the museum’s ground floor, Cally Spooner’s Warm Up (2016), together with several other exhibited works, presents and draws on ideas related to labor and its repetitiveness. Like Sehgal’s, this too is a transposed performance, and presumably revised for a local dancer. In the exhibition hall, a Chinese girl in her early twenties is immersed in her stretching routine, performing it endlessly while moving among visitors at her own pace. Also delving into the theme of “body in labor,” artist Tong Wenmin’s video Choreography (2018) becomes particularly interesting as a counterpoint to its dancing neighbor. The video opens with the artist laying clear tape along her trail across a Yunnan village and then bending down to roll it into a ball of dirt and debris on her way back—ultimately retaining a tactile connection to the place. Whereas the dancer, warmed up and ready, but without a stage on which to perform, is left displaced. In this way, the balled-up tape in Choreography serves as an instrument that affirms a once-present body; the dancer’s ever-rehearsing body, on the other hand, finds itself an apparatus prolonging the memory of a stage; its very meaning relies on that which is absent.

Cally Spooner, Warm Up, 2016/2021-2022, stretches, dancer, duration unknown

Francis Alÿs’s When Faith Moves Mountains (2002) was conceived shortly after the Peruvian dictator Alberto Fujimori’s downfall, in 2000, which adds a nice shade of satire to the project. The video documents hundreds of enlisted volunteers shoveling a sand dune on the outskirts of Lima so as to move it by a few inches in one day. In the ambiguities surrounding issues such as the recruitment methods for volunteers and compensation for labor, to the actual occurrence of this earth-moving operation, a total lack of proof or disproof provides the project’s closest affiliations to the exhibition’s “nothingness”. Facts are not often immediately visible to the naked eye; when the entropy of information diminishes an image’s specific function, faith/persuasion slides into its place. After going through the outpouring of voices, emotions, photos, and text in newsfeeds, here and now specifically, would anyone still believe that “supplies are ample, shipping capacity is guaranteed”, and “the pandemic is under control”?

-1-610x380.jpg)

Francis Alÿs (in collaboration with Cuauhtemoc Medina and Rafael Ortega), When Faith Moves Mountains, 2004, video, color, sound, 15mi. Courtesy the artist

Francis Alÿs’s experiment demonstrates another dual glimpse at reality—where to record, disseminate, and archive such futility is inevitably an exercise of privilege. The Sisyphean “joint effort of hundreds to move a sand dune by a few inches” is enmeshed in our everyday and, judging from the ongoing pandemic situation, has mutated into a tug-of-war between draconian governance and micropolitics; both farcically regard the other as a “dune.” The stringency of online censorship that seeks to scrub away any form of collective dissent in order to optimize “nothing/none” resonates poignantly with the labor reflected in this piece. Much like the mark left on paper by Maurizio Cattelan’s ballpoint pen after it ran out of ink (Esaurita, 1992), this retrospection into the “erased” is the only way for “nothing”—a recurring result with rare exception—to reinstate its relevance, across the “once was” and “will be.”

Setting the repetition of labor aside, the “repetition to zero(null)” approach in our current context coincides with biopolitics and a vivid display of modern governance. At first glance, Peter Dreher’s daily paintings of a water glass in Tag um Tag guter Tag (Day by Day, Good Day; some 5,000 works created starting in 1974), seemed to be a modern twist on the pedagogical allegory about Leonardo da Vinci’s egg-painting journey. Fast-forward to the current lockdown reality: its similarity to my daily schedule is uncanny. Which raises the question, is it true that “the next day will get better”? Life’s intricacies are like the finely attuned tones and brushwork in Dreher’s paintings, their uniqueness gradually worn away by the motif and subdued by the cumulative motions until they dissipate into oblivion. Skills are pruned endlessly and relentlessly over an extensive period. At some point in time a particular strategy or physical motion evolves into an act of meditation and sorcery, which, accompanied by its motif, whirls into a self-assuring cycle.

Peter Dreher, Tag um Tag guter Tag (Day by Day good Day), selected, 1974-2013, oil on canvas, 25.4 x 20.3 cm each

This feeling of “subdued” swooped back in as I entered the space allocated to Roman Ondák’s Clockwork (2014). Caught within this tacit institutional-critique performance, and feeling awkward and somewhat out of place, I blurted out an alias and the time to the attendant before scurrying off. While the name and time records on the exhibition walls should not be overanalyzed in the context of present events, I was drawn to a comment my friend made two years ago: “The nonexistence of a community of people has now been affirmed.”

At times, “nothingness” entwines with “failure.” In aesthetics, “uselessness” is a common term that can refer to “defeat” (incapable of) or “uselessness” (unrequired or overqualified). If one sprinkles class theory onto Mladen Stilinović’s declaration from The Praise of Laziness (1993) that “There is no art without laziness,” one may arrive at “There is no art without surpluses”—art is grasping onto the leisure class as its lifeline. Here, in works ranging from Yoko Ono’s delightfully naïve and childlike metaphors in “Instructions” series, to Fernando Ortega’s Rosa subido (2016), a balloon reachable only via a fully extended ladder, to Robert Grosvenor’s functionless “toy-model” cars (Untitled), all are in favor of “uselessness.” In this sense, “nothingness” is courting classical Daoism to ward off utilitarian values.

By now, the exhibition’s “nothingness” has come to encompass the following interpretations: failure, malfunction, transgression, resistance, reversal, repetition, asynchrony, anonymity, blankness, and even inequality and exploitation. (The exhibition catalog repeatedly mentions that both the artist Li Liao and his employer allegedly exploited the labor of the artist’s wife, Yang Jun, when creating the piece Surplus Value (2018–19), and her name is omitted from the exhibition despite being identified as the artist. This tiny factor contributes quite a substantial aspect of “nothingness” as compared to others discussed.) This overload unavoidably pushes the curatorial framework into incoherency and sets works like Zhang Kechun’s The Yellow River photographs, taken in the central and northwestern regions of China, Gabriel Orozco’s Empty Shoe Box (1993), and Martin Creed’s flickering spotlights (Work No. 160: The lights going on and off, 1996) in a slightly tricky and contradictory spot within the exhibition. That is to say, pandering to the concept’s pluralism and inclusivity leads to disorganization and eventual bruteness. To be fair, the term is complex. In fact many of the exhibited works have approached it through self-referencing statements of failure and absurdity; and rather than procuring something out of nothing, it is a collection of tangible “beings” trying to attain conceptual “nothingness.”

As a museum, when the institution repositions the concept of “nothingness” in Hangzhou’s cultural context with the aim of generating “something”—using capital buzz and its landmark to boost crowd traffic—it transforms the term from one of discursiveness about artistic creation to a seat-filler for what once was a relatively barren local contemporary art scene, undermining its specific potential for a low-brow motive. The exhibition’s claim to be “A Show About Nothing” thus seems blunt and a little flat. Though arguably a public-oriented “something” sounds more appealing than tedious justifications of “nothing.” Seriously, what do we need art for anyway? Amid our harsh and dystopian reality, art feels like nothing but a puff. Perhaps this is why I find Hans Haacke’s White Sail (1964–65) deeply fascinating—an amorphous entity perceptive to all kinds of space, it is Romanticism at its finest. The white sail, riding on a fan’s wind, forms silhouettes in the air and synchronizes everything under the whiff. Here, the everyday is pronounced feral.

展览现场-433x650.jpg)

Hans Haacke, White Sail, 1964-1965, chiffon, oscillating fan, fishing weights and thread, 350 x 360 cm

Ren Yue

Translated by JY Deng