Xiao Longhua: Don’t Tire Yourself Out

| September 25, 2024

Xiao Longhua playing with an African instrument in his studio

Passing by numerous cafés, flower shops, small restaurants, and boutique stores along Julu Road in Shanghai, I found the address and turned into an unassuming longtang (alleyway in Shanghai). I stopped in front of a small concrete building, rang the doorbell, and entered a dim but clean hallway. Climbing the wooden stairs step by step to the second floor, I couldn’t help but squint and observe the objects nearby, such as a complete set of Picture Story Books of Revolutionary Model Operas placed on an old wooden cabinet. At this moment, Xiao Longhua’s cheerful voice called out, “You’re here! This way, this way.” I followed the voice to a corner on the second floor and looked up to see Xiao Longhua halfway out of a door frame above the stairs. “Be careful, someone just slipped here a couple of days ago,” he warned. Indeed, the stairs were narrow and steep, with shoes placed along the edges of each step—Converse sneakers, skate shoes, and leather shoes—accompanying the creaking sound of my every step.

After reaching the top, I glanced to the left and exclaimed in surprise, “So cluttered! And everything is made of wood!” Cabinets were filled with wooden sculptures, toys, and various unidentifiable odd objects. As soon as you enter, you see a giant wooden puppet with an afro, deep-set eyes, and small eyes, with a screen embedded in its body (the work’s title is “/ \”, the shape of the sculpture’s two arms). The studio had many bookshelves tightly packed with books and catalogues in Japanese, English, and Chinese. Masks hung on walls, which were also covered with cards and photos. In short, there seemed to be no empty corners here—birdcages hung from the ceiling, and a fountain-like lamp rose from the floor. Different projects seemed to be in progress on the tables: a pile of paper cuttings, a stack of books, and scattered building blocks. Along the edges of the floor stood a row of short “wooden men,” each with a unique appearance.

In this approximately 30-square-meter studio, a mix of indescribable items from different corners of the world seemed to be exchanging information with each other. Xiao Longhua himself is also an “indescribable” person. He draws comics, teaches animation, designs, sculpts clay, assembles puppets, takes photos, hunts for antiques, explores ruins, and creates artist books. Some of these activities have made him a teacher, some have brought him like-minded friends, some have developed into “artworks” displayed in galleries, and some just happened because—he likes them! He roams and adventures in the world, bringing back treasures to his studio. When visiting Xiao Longhua’s studio, the first question often isn’t “How have you been?” but rather, as one picks up an item, “What is this?” This small attic studio is a crossroads of diverse hidden worlds, and it is also a creator’s complete world, where all curiosities and explorations are met with their corresponding objects. Here, Xiao Longhua is always playing.

A corner of Xiao Longhua’s studio

Xiao Longhua designed the hand-written signage for the studio based on vintage calligraphy of the 20th century.

LEAP: When did you move to this studio? What was the opportunity at the time?

Xiao Longhua: Around 2015, when more and more things were piled up at home, I wanted to rent a studio.

LEAP: There are several desks here, what do you usually do in the studio?

Xiao Longhua: I often work on several projects together, shuttling between different desks. The big desk by the front door can be used to lay out large items, so you can spread out books, use the computer, chat with friends, and do paper-cutting. The desk under the pitched roof was recently used to design the Shanghai part of the Nursery Rhyme Program initiated by the singer Xiao He, and I do a lot of paper cutting and carving here, so it doesn’t matter if it’s a little messy. There’s also a smaller woodworking desk by the window.

LEAP: The studio doesn’t feel like one has to be serious here, it feels like it’s “so much fun” in the first place. Some of the collected toys and instruments are newly made, some are the works of artists, and some are abandoned things that you have picked up. But when they are put together in the studio, one can feel the commonality you see in them. They are like some wild, non-conformist, strange life forms.

Xiao Longhua: I love collecting. Over the past decade or so, Shanghai has undergone significant changes due to demolition and reconstruction, resulting in many ruins and thrift markets, perfect for treasure hunting. Sometimes, I come across something intriguing on the road. For example, the frog in front of you was made by a granny using cheap cardboard straps and sold by the roadside—I couldn’t resist bringing it back. The rubber mat on the chair you’re sitting on has a checkerboard pattern; it is actually a mold used in a sugar factory that I found in Guangxi.

LEAP: All this collecting also seems to give you a lot of real, object-based connections to the world. Would you consider yourself a collector as well?

Koryuhana: I’m kind of a “treasure hunter” haha! Do you know the Japanese magazine Taiyo (The Sun)? (LEAP: I’ve never heard of it.) Taiyo is a very famous monthly magazine that was published in the 1960s by Heibonsha, an old Japanese publisher, and it’s been published in many series since then. The theme of this one is “treasure hunters”, which is what we usually call “collectors,” but the clues that each of the collectors in this book chooses are particularly strange. For example, Tadanori Yokoo collects half-lying figurines, while another treasure hunter collects floating objects from the sea and river, and keeps a wooden boat in their house. These are not expensive things in the worldly sense, but these collectors find them interesting, and they are “treasures.”

LEAP: Let’s talk about this studio. Last time you said this loft was part of a family house. I just saw a sign on the first building in this alley that says that building is the former residence of your grandfather, the painter He Youzhi’s former residence.

Xiao Longhua: Yes, my mom’s family used to live in the first building in front. My mom’s dad He Youzhi grew up in Ningbo with no one to turn to and was brought to Shanghai by his uncle. According to Grandpa, he came to Shanghai empty-handed, “without a place to stand,” and did all kinds of work. Since he drew folk paintings for the Spring Festival in his village as a child, he later apprenticed at a workshop of picture story books in Shanghai and eventually joined the Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House. The area around Julu Road was a hub for publishers and literary figures, and he settled here in the 1950s. The building where my studio is located was actually my paternal grandfather’s house. My dad’s mom, who had seven children, raised them all in this building. Over time, they gradually moved out, and I ended up renting this studio from my aunt. My parents grew up in the same longtang and knew each other from childhood, and I was born at the First Maternity and Infant Healthcare Hospital not far from here. So I grew up in this area.

“Wood Man” series, 2019

Wood, plastic, metal, paper, and leather

LEAP: And would you say your study of art was influenced by He Youzhi as well?

Xiao Longhua: When I was young, some of my cousins and I learned painting from Grandpa. I took Chinese painting courses, which included books like How to Draw a Cow and How to Draw a Tiger, but Grandpa told me not to read those books. He was actually quite relaxed about teaching us because he was very busy and didn’t have much time. However, I would watch him paint, and I got to see firsthand what an old master was doing, how he did each step, and the entire process. Although Grandpa usually didn’t allow anyone to be around while he was painting, I was quieter as a child and could watch for a while. But I could only watch for a short time—drawing the outlines was quite tedious. When I found myself getting restless and wanting to make a sound, I would leave.

LEAP: Do you find it onerous to draw on your own? Did Grandpa teach you to draw picture story books too?

Xiao Longhua: After I started to draw on my own, I slowly discovered some of the joys of drawing. When I went to the park, my grandfather would teach me how to sketch, and how to capture the characters, including some mnemonics for memorizing scenes.

LEAP: What is this method?

Xiao Longhua: It’s just turning it into keywords. Let’s say you guys just came in and went onto the third floor, right? That’s a reddish mottled door frame, and above the door is this iron guardrail. So my memory is that when I arrived home in the rain, I was ecstatic to hang my umbrella temporarily on this iron rail, and then pull out my key, unlock the door, and that’s comfortable. I can record these scenes by turning them into a describable and particularly straightforward language without adding adjectives. When sketching, because people go away very quickly, you have to react in a few seconds, catching only the most distinct features (like a few parts of the joints) and also grasping the overall state of the person.

LEAP: That’s awesome! This is actually a game from when you were a kid.

Xiao Longhua: Yes, it is a kind of training method. Grandpa didn’t have any formal drawing lessons, so he especially wanted me to learn drawing systematically. But when I was in the preparatory class for sketching in high school and middle school, the training was a bit difficult. I would sometimes skip school and run out, but Grandpa would still come to check on me.

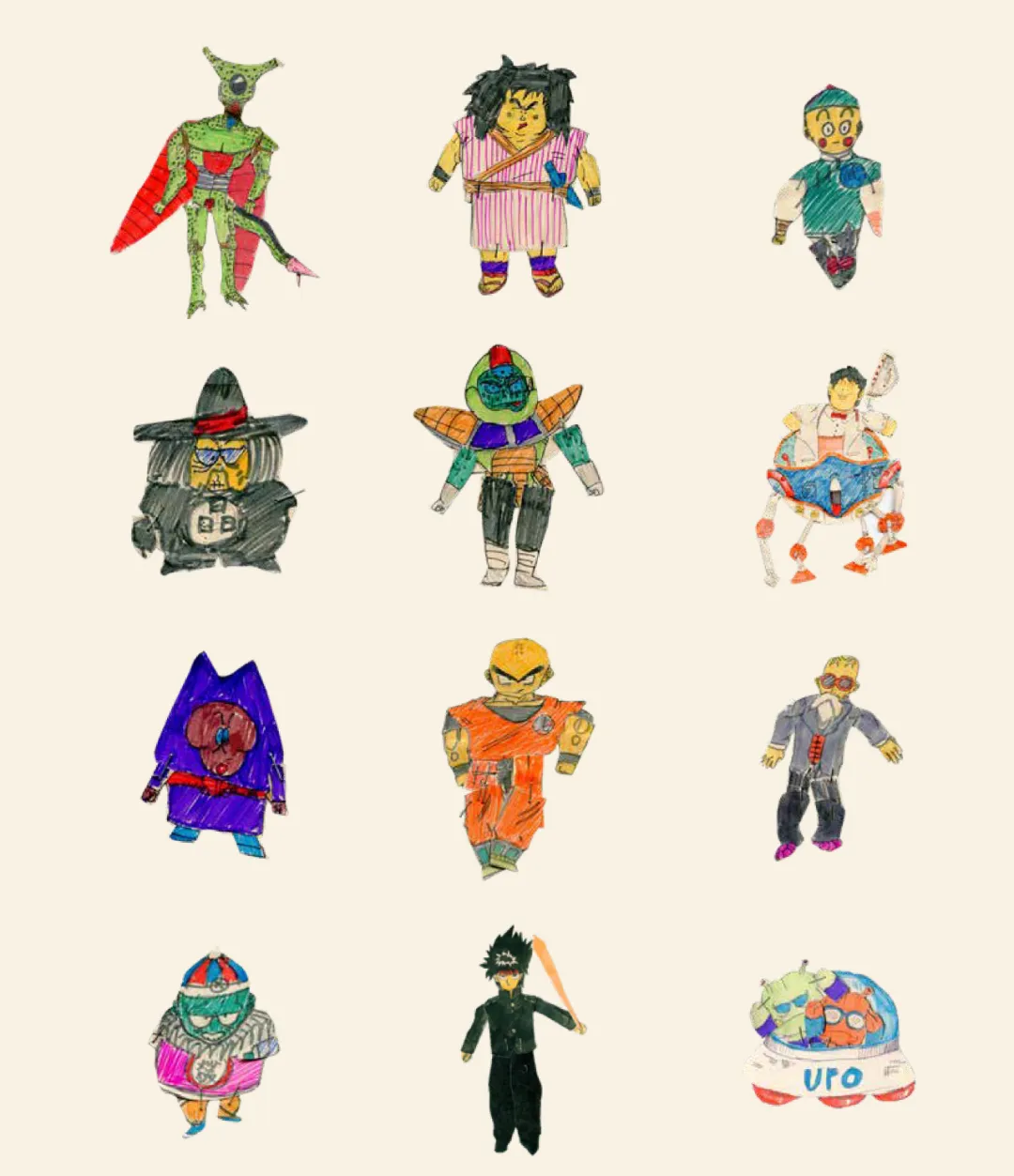

Paper toys based on characters from manga Dragon Ball, Ararai, and YuYu HakushoHandmade by Xiao Longhua during elementary and junior high school

LEAP: You majored in oil painting at Shanghai University and painting was the most orthodox discipline at that time. It must have been in accordance with your grandfather’s wish?

Xiao Longhua: Yes, although Grandpa knew the roots and provenance of his art (he had an autobiographical picture story book just called “I Come from the Folk”), he always wished in his heart that he had been systematically trained, and he wished that I could be too. Since everyone at the time felt that this kind of realism and sketching was the best direction for the future, he would let me learn it and not repeat his own wild ways. There were a lot of contradictions here, and sometimes he would say, “There is no way to learn art,” “Academies can’t teach artists” and “Artists don’t have to go to school.”

LEAP: It must have been difficult for you at the time, but you don’t show a lot of academy training in your art now.

Xiao Longhua: Actually, I’ve always had my own outlet. Let me show it! (Xiao Longhua took out his high school textbook from a locker, flipped it open, and pointed to the Japanese anime-style vignette in the center.) I drew all over the textbooks at that time, and would make up all kinds of stories, such as something weird, or a classmate getting cut in half or something. I would also draw serialized comics in my books, all using my classmates’ real experience as materials. And I never had my book to myself. For example, if the teacher asked me to get up and read a passage, I didn’t even have my book—because my book was being passed around the class. So all the pain of test-taking in those days was eased in that.

LEAP: It’s really about using your imagination to let yourself escape in a very difficult moment, and taking everyone with you. Storytelling seems to be something you’ve always loved to use in your work, and a lot of it comes from your life.

Xiao Longhua: Sometimes at class reunions, I talk about what my classmates used to do and what they wore at the time. They have all forgotten, but I still remember! I grew up with Shanghainese burlesque and comedy, such as the most well-known Three Hairs Learning Business (1958) and 72 Houseguests (1958). I love to tease and capture the parts of life that are comedic.

LEAP: You’re already having fun observing life.

Xiaolongha: Yes, I would spontaneously write an interesting scene down, turn it into a paragraph and keep telling it, and then draw it. When I was a kid, we had a dual-cassette recorder at home, so I could talk while the tape was recording. I would record my own comedy.

A bookshelf in the studio, with toys by Anraku Ansaku, Hideyasu Moto, Grody Shogun, Hideshi Hino and other artists on the middle shelf

LEAP: Did you watch Ultraman and those animations as a kid?

Xiao Longhua: Animation is something I’ve loved since I was a kid, and I especially admire some of the animations from Shanghai Animation Film Studio (SAFS). At that time, Grandpa also thought highly of these animations, but he said not to look at Japanese things. He felt that the Japanese animation production started by Osamu Tezuka is a business model. It just moves the arms, moves the mouth, and relies on subplot to do the effects. But now, looking back at the works of SAFS, I think they are actually art films, and different from today’s cartoons or anime like how art films and popular TV dramas are different. But I’ve always loved Japanese anime, and when I was a kid I even made a lot of my own toys.

LEAP: What kind of toys did you make?

Xiao Longhua: (Took out a cardboard box containing animated characters he drew on pieces of paper from elementary school through college.) When I was a kid and first started reading Japanese comic books, I wanted to buy toys of these characters, and if I couldn’t buy them, I had to make them myself. Because the comics were all in black and white, there was little reference when it came to drawing colors, and it was a long time before I realized I had painted them wrong.

LEAP: It’s so much fun too. It’s also especially precious to keep them till now. You seem to find the fun in so many things and approach them with such seriousness.

Xiao Longhua: Indeed, I find it hard to stick with something if it’s not fun.

LEAP: So how did you stick with it when you were learning to paint?

Xiao Longhua: It was a simple thought at the time. I’ve always loved animation, but I believed that four years of oil painting in college would provide a solid foundation. I could learn techniques in oil painting, the study of materials, and the ability to model. With these skills, I could explore other areas. So, as soon as I graduated from university, I said goodbye to oil painting and went directly to Beijing.

LEAP: It was 2004, and you went to the animation department of the Communication University of China, but not as a formal student.

Xiao Longhua: At that time, I told myself that I would not pursue postgraduate or take any more exams. I just wanted to learn the craft and study animation. As soon as I arrived in Beijing, the space around me suddenly expanded. No one knew me, and I could experiment and try to shape new personalities different from my original ones. Back then, Beijing was a haven for pirated and bootleg DVDs, and there were many smugglers and traders, all of the artists’ names were unfamiliar to me. I would just save 200 Yuan from my monthly living expenses for meals, and the rest was spent on CDs, DVDs, and old magazines. Students would also swap their collections with each other. I’d lend a movie I finished watching, and they’d lend me theirs, so we could watch together. The atmosphere was very enriching.

LEAP: You should still have some of the DVDs and magazines from that time? It feels like you collected things in a particular direction as well.

Xiao Longhua: Of course I kept them! In those days, buying DVDs was like playing a game of Guess Who, not only did you have to feel out where they were sold, but you had to take your time and go back and forth with the dealer. The next time you visit the store, he might just ask you to go through another door, into another room, and show you a different batch of DVDs. At that time, I was shocked when exposed to new information, and I just dived in. I feel like a lot of the people born in the 1980s love hoarding as much as I do, probably because on the one hand we’re culturally starved, and on the other hand we have to deal with the huge uncertainty that hangs over cultural items. There may come a day when you can no longer contact the dealer. But the upside is that we have honed ourselves to be very sharp and able to find some clues to reconnect with the information pipeline.

Toys of the first generation of Ultraman (Umezu Kazuo version) and monster toys designed by Imiri Sakabashira

LEAP: You went back to Shanghai and contributed to the comics compilations CULT Youth’s Choice (Part 1 and Part 2 came out in 2007 and 2008 respectively) and SC Comics. At that time, you were doing very well in comics and illustration, what made you venture into these three-dimensional sculptures and installations? It might also be important to ask you first, how do you call or define them?

Xiao Longhua: I looked it up, and what I’m doing might be called “object art”, that is, “the art of objects.” Around 2010, when my partner went to Beijing to study bookbinding, I was alone at home and had more space, so I could hoard more “garbage” (laughs). No one watched me, so I could turn the whole apartment into a studio. I then started to use recycled scrap wood and make three-dimensional things, hoping to get out of my old track. I had been illustrating too much, but I wasn’t content to just repeat certain techniques.

LEAP: It turns out you had to find another place when your partner got back.

Xiao Longhua: That’s right, that’s why I came to this studio.

LEAP: How did you come up with the idea for the series “Large Migration”? They’re more like strange lifeforms you created that don’t exist in the world.

Xiao Longhua: I started by putting the materials together like building blocks, like forming a shape. At that time, I was very proud of putting together something and making it look like an animal or a human. But after a while, I would see the end of the route, and I felt that it wasn’t fun enough. I had to set up another way of playing. “Large Migration” grew out of this.

LEAP: There’s some sense of not letting yourself become too skilled. A lot of your work is also a bit like “demos” in that you don’t strive for a particularly beautiful state.

Xiao Longhua: There is an alternative art school in Japan called Bigakko. One of the students who graduated from the school, Minami Shinbo, who wrote My Illustration History 1960–1980 (2019), talks about not being too obsessed with mastering a skill too quickly. He said that you must be careful when drawing: “You must not progress too fast!” “Be careful of progress!”

LEAP: You seem to be really influenced by Japanese culture, and definitely not just in terms of anime.

Xiao Longhua: Many Japanese publishers do a particularly good job of researching and narrating the history of specific topics. They give me telescopes to see far away, and reading them is like island-hopping. I can be shuttled to many different places.

LEAP: Tell us about your toy collection. You collected a lot of toys from the Showa era in Japan, especially toys from Japanese special effects (tokusatsu) cinema like Ultraman and Godzilla.

Xiao Longhua: Yes, as a kid I watched the airing of Ultraman on TV, and that’s where I developed my interest.

LEAP: You mentioned last time that the image of Ultraman wasn’t created completely out of air.

Xiao Longhua: I think that Ultraman is very similar to the tattoos on the early Japanese Jomon people! There was another Japanese statue maker, the monk Enkū (1632–1695), who carved thousands of Buddha statues in his lifetime, but his statues were particularly wild, unlike the traditional. Ultraman’s mouth is very much like the shape of the mouth on a Buddha statue by Enkū.

“Massive Migration” series, 2016–2019

LEAP: If feels like you have so many threads and topics going on in one conversation, and any one of them could lead to a new direction to talk about.

Xiao Longhua: I probably don’t have a so-called “specialized area.” I have many points of interest, and it’s comfortable for me to keep moving in the neural network formed by these points. I enjoy things that are a bit ambiguous, and my research is also based on my interests and my own creation. I can see the connections between many of my favorites.

LEAP: I feel that in an information explosion or postmodern state, you have found a lot of cues to collage and reorganize. But wouldn’t you want to become an expert? Or particularly good within a system, let’s say in contemporary art?

Xiao Longhua: No. I have never considered relating myself with the contemporary art system because I chose not to live by it. When I go to art museums and galleries, I focus more on the artists themselves and their works. For myself, I would prefer to make something related to my life. At the end of the day, art is still life—not the consumerist lifestyle that magazines promote, and quite simply, you gotta have fun, right? You come to this world, you can create a really great life of your own and feel fulfilled. Some of my friends are always saying to me, “How could you live so freely?” and my life isn’t really like that. I just don’t hold onto grandiose meanings. Carrying a big flag or something grand is not my way. Of course there should be people who do that, but I am definitely not one of them.

LEAP: So would you want to take something that’s smaller in scale now and reproduce it with more volume and funding?

Xiao Longhua: I don’t think the purity of my stuff is lacking. I may prefer to be a hybrid artist, like Zhang Guangyu (1900–1965), who can do practical design as well as create for himself, even without external recognition. I want to do both, but I don’t think it’s a good idea to pick only one side. It’s kind of like the marine iguana, which can be found in swamps and under the sea, but still has to bask in the sun when it’s especially cold.

LEAP: Both sides can benefit each other and be cross-referenced.

Xiao Longhua: Yes. I love the illustrations Grandpa drew, they are particularly amusing. Although Grandpa made a lot of large works, I really liked some of the short stories he drew for the newspaper. Those were places where I thought Grandpa was very experimental with composition and he played with it, with an open mind. Even in his larger works, I prefer the offbeat little characters. I think that’s more of his own texture.

LEAP: Our conversation always seems to circle back to your grandfather.

Xiao Longhua: Indeed, many of my choices and perceptions are deeply influenced by my grandfather. One of the greatest gifts he gave me is that I am not concerned about many things. Having seen him reach a very high position in his professional field and in society, I’ve seen what it was like. So, as you can imagine, would I still desire that position?

LEAP: Would Grandpa have wanted you to get to a higher position?

Xiao Longhua: Later he just said, don’t tire yourself out.

Interviewed by Nie Xiaoyi

Xiao Longhua was born in 1982 in Shanghai, now working and living in Shanghai. He works in the fields of painting, comics and sculpture. Xiao Longhua’s work explores possibilities of new creations and interactions between materials based on their raw shapes, textures, colors and nature, seizing upon the impromptu relations and narrativity through them.

He Youzhi (1922–2016) was from Xinqi, Beilun, Ningbo, Zhejiang, but he spent most of his life in Shanghai. As a renowned artist of “lianhuanhua” (a traditional Chinese palm-sized cartoon books), he was known for his fine line drawing. Throughout his life He Youzhi illustrated five versions of Little Erhei Gets Married, and was responsible for the widely disseminated propaganda picture story books such as Great Changes in A Mountain Village and Chaoyang Valley. At the turn of the century, he illustrated The 360 Trades in Old Shanghai. He served as a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and an executive board member of the fourth session of the China Artists Association. In 2022, Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House published the 26-volume Complete Works of He Youzhi. He Youzhi was also the Xiaolonghua’s maternal grandfather.