FROM NYC TO HONG KONG: 2 GRAPHIC MEMOIRS

| 2015年01月29日

Copyright © 1991 by Pantheon Books

WEB EXCLUSIVE

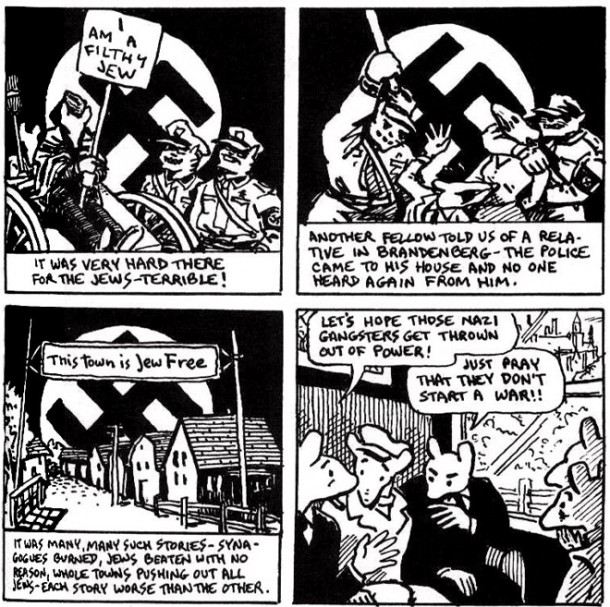

The evening of January 12th, an unlikely speaker gave a presentation at The Bookworm, Beijing’s oldest bookstore-café: American cartoonist Art Spiegelman. Although for the most part unknown in China, in the U.S in particular, Art Spiegelman has become practically a household name—if there’s one book recommended to “ease” people into the graphic novel, it’s Spiegelman’s seminal work Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (1991). There’s a kind of irony to the fact that for some, Maus has come to signify an entire medium, when in actuality, the book, a multi-layered conversation between Spiegelman and his father, a Holocaust survivor, questions and subverts the representation and genre of comics. As much historical document as it is memoir and fiction (the Jews are mice, the Nazis are cats), Maus is one of the first examples of using the “low” medium of hand-drawn comics to record both personal and historical trauma.

Panel from Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, by Art Spiegelman

Copyright © 1991 by Pantheon Books

Although it was fantastically surreal to see Spiegelman, alongside fellow New Yorker staff members Françoise Mouly and Susan Orlean, in Beijing, none of their presentations addressed the elephant in the room: China. Mouly and Spiegelman presented images of past New Yorker covers and addressed the recent attack in Paris on satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, but made no attempt to include China in the global equation. I found myself unsatisfied, waiting for someone to make connections between Spiegelman’s work and comics in China. Comics may be a juxtaposition of word and image, but their emphasis on the visual often transcends cultural boundaries—the most recent issue of Special Comix, China’s leading independent comics anthology, contained work from cartoonists all over the world, allowing the images to speak for themselves.

By Hok Tak Yeung

Copyright © 2002 Slowork Publishing

One thing I noticed, however, was that although zines, anthologies, and short stories seem to be the norm on the mainland, graphic novels have a much longer history in Hong Kong. It was here that I was able to make connections between the graphic novel and memory, as reflected in Hok Tak Yeung’s 2002 book How Blue Was My Valley (锦绣蓝田). The graphic memoir, told in stream-of-consciousness style, has more image than text, and the text it does have is so casually scrawled that the reader has to squint to read it. The colors are flat, saturated, the palette changing from psychedelic to monochrome between chapters. Although How Blue Was My Valley reflects on broader historical developments (Hong Kong in the 1970s), it mostly contains snapshots of everday life. Many frames contain impossible viewpoints, such an architectural plan of a builidng with anonymous inhabitants in sillhouette, allowing the narrative to oscillate between first- and third-person. By overlapping time frames and intertwining past and present, Hok creates a reading experience that unfolds through time and space. In the end, a flatter, more “cartoonish” style, in addition to a nonlinear timeline, comes closer to mirroring memory itself than hyperrealism ever could.