Korakrit Arunanondchai: The Denim Painter’s Universe

| 2015年12月09日

All images courtesy the artist, C L E A R I N G (New York, Brussels) & Carlos/Ishikawa (London)

The thing about the denim painter’s universe is that, once you get sucked in, it’s hard to climb back out. Korakrit Arunanondchai imbues his work with a charisma that is massively seductive, and speaks directly to the viewer in a call and response of interpellation: “I am a machine / boosting energy into the universe / and you / you are the spirit in the wind around me / a thought turned into a vector and projected into the air. From the artist in person to the artist he portrays in his work to the narrative of his work, Arunanondchai threads together a logic of addiction from which it is difficult to withdraw. I literally cannot step away from the work; I sing bits of his soundtracks to my daughter when she goes to sleep at night, and listen to his comforting voiceover in a minimized tab while I write at the office. “You said imagine the near future / when our eyes have moved to the sky / we will be looking down at each other / a connectivity equal to an escape.” Pulled into the orbit of a deep empathy—a gravity in its own right—it is this radical generosity that connects everything, settling the viewer into multiple positions within the universe of the work and then going on to wrap thin gossamer threads of feeling and meaning around and around and around. In the end we are cocooned, paralyzed but for the hope of a sequel.

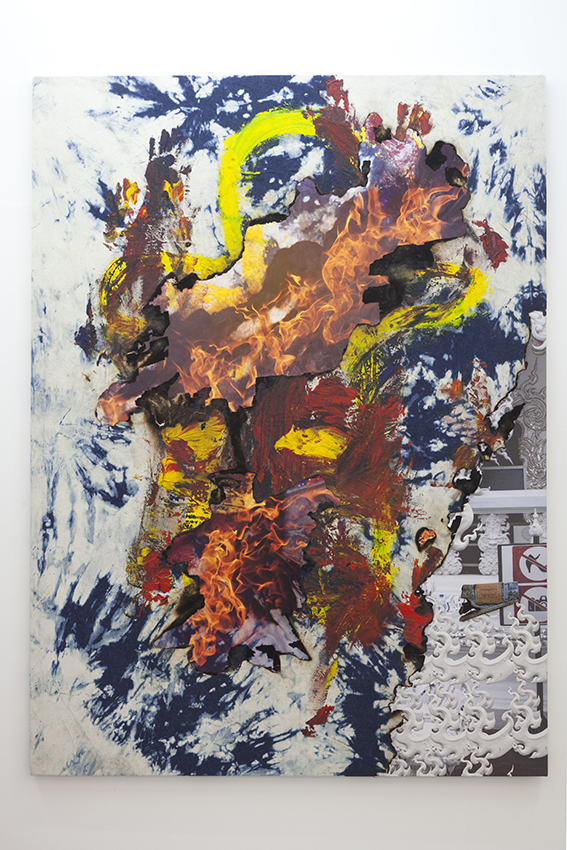

Many people, particularly from the nightlife world, are initially drawn into Arunanondchai’s work through the heavy fog of affect in his live performances, often featuring the performer boychild. Others, from the global financial set, come to him through denim paintings, which seem collectible and commodifiable and cool. Both pathways are misleading red herrings. Arunanondchai’s performance is actually not about liveness or experience at all; the first law of the denim painter’s universe is that there is no denim painter. The denim painter is a character, which Arunanondchai describes as “basically just me but more like the art character of me.” More a representation of the self than an avatar, it is an open acknowledgement that art practice almost necessarily establishes a filter through which to communicate with an audience. The denim painter’s work is to create a structure for the practice of abstract painting, an action that he then delegates back to Arunanondchai, who does the composition of the work, the processing of digital elements that go into it, the burning of denim, the body painting (certain tasks, like gluing and bleaching, are delegated). In the denim painter’s world, these pieces are created almost by the elements themselves: lighter fluid, the wind, the sky. Variables are more significant than choices.

Arunanondchai, on the other hand, believes that no painting is interesting by itself, outside of its author’s function and its framing or story. His work creates a narrative of the denim painter’s personal evolution that plays out in parallel with his own growth as a person and an artist, struggling through similar issues but making it all public, allowing himself a critical distance from his own thoughts and experiences. Through this strategy he sets up a series of mirrors: east and west (Bangkok and New York), reality and fiction, sincerity and sarcasm, art and life. Denim becomes a sponge that absorbs and swallows up the characters and objects that surround this universe on both sides of the mirrors. Arunanondchai’s practice is structured as a double performance, a life-performance of a performance artist. He must know how to make his work work, and how to transcend this work and make the making of the work work.

Arunanondchai traces the origin of his current practice to 2007, around two years into his time at the Rhode Island School of Design, in Providence, when he began making intuitive line drawings that he would then digitally manipulate in Photoshop. After about a year of experimenting with these forms, he started making “trippy” landscapes that he combined with the Photoshop forms by printing silkscreens, ultimately onto three-dimensional objects. He graduated from RISD in 2009 and moved to New York, where he attended Columbia University for his MFA. By 2011, entering his last year in the program, he realized that he had become more interested in what was happening outside of the painting proper, and in how meaning was constructed around the object itself. He began minimizing his choice of materials into their primary elements: fire and denim, to start with. In using fire to burn denim and then transforming the photograph with graphic representations of fire, he found a way to make the past physically present in the present—to allow his past to produce the present.

Arunanondchai is often rumored to have had a mythical career as a pop musician in Thailand; the story isn’t really quite true, but it reflects his sensitivity to the use and abuse of the media. The rumor is sustained, perhaps, by the charisma of his musical performances in his videos and live performances, and it does seem useful in distancing himself from the more cynical path of the typical emerging artist today. Arunanondchai does put stock in the power of performance, but more often as a motivating tool than as a spiritual experience. In his video, frequent collaborators like Alex Gvojic and Rory Mulhere work within a loose framework devised by the artist, who is able to fully enter into his performance while others take over the direction: “There’s no way to be outside yourself and inside yourself at the same time.” Arunanondchai refers to Thomas Hirschhorn’s formulation of art as energy divided by matter. As a performer, he is an active piece of matter with a certain amount of energy, but when he is taken out of the experience in the exhibition content that energy has to be locked up in the liveness of the installation.

Many of the press releases and interviews that Arunanondchai offers to the media accept, as reality in his first universe, that certain realities from his denim painter universe are true in this world as well. This construction allows him to think critically through his position in the art world, and to use this very concrete, very individualized notion of identity to disappear and reappear inside and outside of his work. He first reflected on his paintings as minimal, process-based, tasteful; the fact that they drew on “cheesy” elements like bleached denim and stock images of flames allowed him to subvert this accidental confidence. The point is not to start with something cheesy and make it classy; the art context does that on its own anyway. Arunanondchai seeks more to draw on the emotional apparatus that allows this to happen, producing a combination of slick production and breathless earnestness. Film is the central force here; the art context is a marriage of convenience, a self-organizing structure for objects that frame the viewer’s relationship to the moving image. Paintings and sculptural elements from Arunanondchai’s universe never go alone. They may function as autonomous objects, but they belong in relation—physical and spiritual—to everything else.

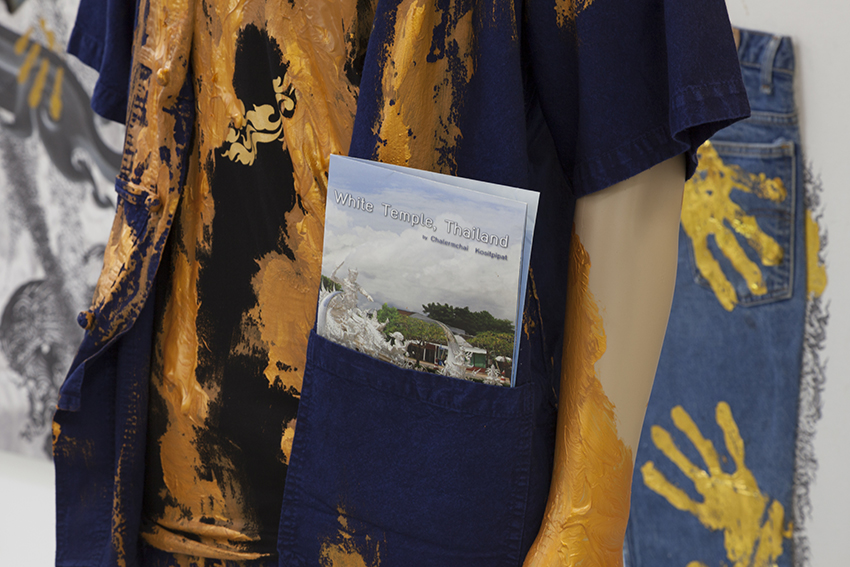

Now that his performance of the denim painter is beginning to come to an end, the walls between these worlds seem to rebuild themselves. We must remember, after all, where his signature style of body-painting on denim came from to begin with: Arunanondchai calls his paintings derivatives of the female go-go dancer who painted with her boobs on Thailand’s Got Talent, whose history was almost elided after the show hired another male body painter to found a new school of Thai action painting. It was in 2012 that Arunanondchai watched as Thai artist and architect (a Buddhist modern master, in a way) Chalermchai Kositpipat went on television to offer a formal critique of the talent show; this collusion of action and discourse allowed him to realize that he could bridge his painting practice with these broader questions of circulation through storytelling. This is when Arunanondchai first became the denim painter, in the video 2556.

A year later, in 2013, Arunanondchai shot the second video in his trilogy, 2557. In this installment, his twin, Korapat, plays the denim painter (or perhaps Korakrit himself—it’s hard to say), and Korakrit (or the denim painter) plays his brother, outfitted as a Manchester United fan, as the two take a road trip to the White Temple, the popular icon of Buddhist pastiche designed by Chalermchai. The film takes the form, more or less, of the Chinese road-buddy comedy Lost in Thailand, except that, in Arunanondchai’s version, Korapat gains magical powers: a Buddhist gold-hand painting technique. In his paintings from 2013-2014, and in the videos from that period, these techniques merge under the framework of fraternal bonding: denim, gold hands, red and yellow bodies, fire. Gradually, into 2015, his paintings started to incorporate more media material, including film stills from his own work and from other cinematic references, like Apichatpong; memory began to replace history as the primary tool by which the past shapes the present. This logic is exploded as its most extreme iteration in the middle of 2015 at the Palais de Tokyo, where the denim painting becomes a stage or landscape out of which objects grow organically. In his most recent video, Arunanondchai speaks exclusively to Chantri, a spirit embodied in a drone who becomes his only audience—a conduit through which he speaks to us.

Arunanondchai’s universe is defined by the symbolic references of denim, fire, water, drones, motorcycles, and the yellow man—the empty silhouette that appears as a target in his body painting exercises and an architectural plan in his installations. Birth, death, water, fire; the scene is so elemental that it becomes trite, and yet the artist’s golden touch manages to keep it alive through a complex network of references and appeals to affect. In his telling, these grand narratives are so “washed out” that they can be applied literally anywhere. Arunanondchai is not naive, and his approach can often feel cynical. He speaks of stereotypes of kitsch and copying in Thai visual culture, reproducing the generic elements of flea market paintings with golden t-shirt printing styles instead of gold leaf. Like his alter-alter-ego, he comes to the technique of gold painting by being a tourist at a temple. Structurally, the work is diaristic, with prosaic narratives slipping across media and across factual and fictitious elements. He equates the burning of denim, perhaps the first and strongest symbolic act in Arunanondchai’s practice, with the burning of joss paper in Chinese culture, through which an action of the everyday lifts one to the unknown (he finds another echo in the magical effect of sitting around a campfire in Maine).

Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3 (Trailer) from Korakrit Arunanondchai on Vimeo

In Arunanondchai’s most recent turn, spanning the installation series “2558” and the film Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, the drone takes a central role: its enhanced mode of viewing represents something like astral projection, inside of something but also outside looking down. In an exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo in the summer of 2015, this transcendent viewpoint took in an installation of mannequins, electronic components, foam cabbage heads, vehicle parts, and video monitors before descending into a “fountain of entropy.” The silhouettes of mannequins surrounding the viewer recreate a nightmarish cinema. These installations often look chaotic, but Arunanondchai is incredibly attentive to the level of detail that goes into them. In “2558,” the exhibition at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in late 2015, the silhouette of the yellow man gives structure to the installation: one half of his silhouette is traced in electrical wiring running up and down structures supporting paintings and objects in one room, while the other half is laid out in body pillows on the floor of a video screening room, forming a circuit of biological and electrical energy. This circuit is repeated in a miniaturized architectural model in a fish tank otherwise inhabited only by a silver arowana, a sublimation or elevated version of the snake, naga, that swallows the exhibition. Fragmented images from the tank are displayed on a video monitor at the entrance of the beginning.

The drone, the giant bird known as the garuda, comes full circle as a tool or subject of surveillance. But the drone was actually present in the film trilogy all along, functioning in the last portion as a manifestation of the character Chantri, the addressee of the denim painter’s literary epistles in the manner of the letters read by the narrator in Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil. Chantri is far away but maybe, sometimes, close; the space between the drone and its gaze can be infinite or infinitesimal. Arunanondchai persists in talking to a void until that void performs itself into the role of a character. If the denim painter is an artist who is not-quite-Arunanondchai, Chantri is the filter through which he can convey ideas both more honest (able to say things that he would never personally admit) and more bizarre than Arunanondchai himself. Video can hold at bay the self-awareness of life. The denim painter trilogy follows a story arc that is more nebulous than its mythological structure might suggest, beginning by moving through art history, personal memory, and finally a collective present. There is no easy plot map here. The project more resembles a proper franchise with trailers and other horizontal spatial relationships that one sense more than comprehends. Aside from the main storyline (2012-2555, 2556, 2557), there are a spinoff series (Painting with history), a series of negations (Letters to Chantri is a negative of 2556), and sequence of derivative products, like My Trip to the White Temple, a hypothetical advertisement for Thai tourism. In speaking to the drone, he can move across this cartography at an intimate distance from which artist and viewer alike can see things as they are.

This ecology involves a rapid cycling of material. Most of the denim surfaces that end up in Arunanondchai’s paintings were first used as flooring for live performances. (A painting shown at London’s ICA in the fall of 2014, for instance, originated on a stage used for a performance at MoMA PS1 that spring, while the set for the London performance ended up in the paintings exhibited at the Palais de Tokyo in 2015; some paintings shown at the Ullens Center started out as body paintings in Miami in 2014. and even the denim rags with which Arunanondchai wipes his body after performances are retained.) He understands his entire practice as a story with various temporal and geographic branches more or less related to a central thrust, and the material must steep in its own juices to end up making sense. Video content, too, is often reused, with shots made on one location ending up in videos released years later, and behind-the-scenes outtakes occasionally ending up in later iterations, further blurring the denim painter’s fantasy and Arunanondchai’s reality. (One video is about the making of a music video, and the music video itself was later independently released.) It’s reincarnation for the twenty-first century.

One of Arunanondchai’s big ideas emerges here in the relationships between garuda, naga, and Chantri. The great triumph of his work is the construction of a universe in which the denim painter, the art world to which he belongs, technological objects, and mythical spirits can coexist. It’s a technoanimism that doesn’t feel out of place in the current intellectual landscape, but Arunanondchai manages to weld it to a postcolonial-inflected kitsch sensibility. He refers to a European 1970s documentary that called Thailand “The Land where Spirits still Exist,” but he sees this as more empowering than anything else; his own family, highly educated and living everywhere from Taipei to Washington DC (his mother, speaking French, gives voice to Chantri), makes certain decisions in consultation with spirits that Arunanondchai refers to as forms of “abstract information” that can sometimes take concrete form. He sees cameras and other categories of tools for digital processing in exactly the same way, connecting us to an invisible network that makes up the contemporary landscape. The denim painter gathers material that would be labeled “problematic” and tries to show its truest possible reality, and then to make peace with it. (He shot his second video entirely in Maine, but many viewers still find a Thai exoticism.) This is the artist’s approach to historical and lived traumas. The viewer is ultimately happy to be manipulated, as if the artist (Arunanondchai, not the denim painter) were just another ghost in the machine.

Arunanondchai belongs to a new breed of artist who has stopped trying to make new cultural infrastructures like spaces and collectives, and instead focuses on making new structures within his work that can function in their own way: the production of objects for exhibition supports a much broader life process, and vice versa. He creates a new world in his work, one that is contiguous with ours but does not necessarily subscribe to the same ideals or habits—it is not a didactic representation, and for this reason cannot be held captive to the logic of the world as it is, or even as it should be. In using the denim painter, Arunanondchai builds a new universe in the gap between nature and digital life, between the experience of place and the experience of the cosmopolitan non-places that structure it, between identity and the anxieties of its expression to a global public. He is comfortable with appropriating imagery and symbolism for the sake of a good story, but ultimately all of the feelings and ideas floated here are real, and that’s what makes it all so addictive. The viewer is manipulated, but never abused. Arunanondchai’s editing of the world—the filter that his self-presentation creates—is both formal and affective, taking place in his own experience of film footage during post-production as he moves forwards and backwards through his memories. Time is a spiral, and Arunanondchai’s central trauma is in the uncertainty of experience—material or immaterial, digital or sculptural, it cannot last. He is a machine, one built to capture your vector in meaning if not in body.