SONG DONG & YIN XIUZHEN: THE WAY OF CHOPSTICKS III

| October 23, 2011 | Post In LEAP 10

At its most elemental, Song Dong and Yin Xiuzhen’s ongoing collaborative project “The Way of Chopsticks” is a simple binary: as with husband and wife, one chopstick needs the other in order to properly function. As with the previous two installments, also shown at Chambers in 2002 and 2006, “The Way of Chopsticks III” finds its formal core in a pair of oversized chopsticks, visibly similar in dimension, but this time longer than before at a vaguely symbolic twelve meters. The two halves are created in secrecy, the artists— who normally work in separate but connected studios— having agreed on basic rules and then forbade themselves to see or speak of the other’s half before the exhibition. Although it is easy to suspect that this “secrecy” is a farce, such doubt is superseded by the fact that, real or not, it is this enforced separation that defines their only openly collaborative work. Harking back to earlier moments of “rule-based” work dotting recent art history, the arrangement also implicitly reveals how the couple have otherwise resisted the temptation to fold two parallel solo practices into one.

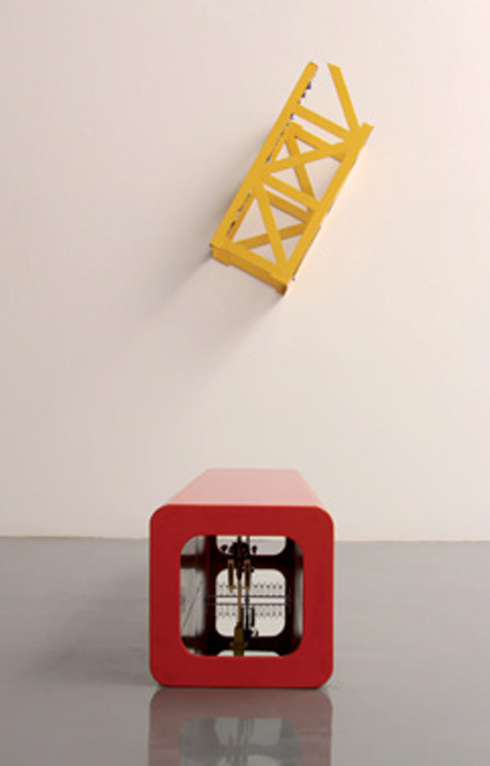

In the main hall of the gallery we see the complete, untouched results of this diligent plotting, resting side-by-side on the gray concrete floor. To the left is Yin Xiuzhen’s chopstick, imperial yellow and inspired by the towering construction cranes seen all over China’s skies, its cold steel girder frame poetically punctuated by fragments of garments— a nod to the “second skin” of used clothing her work has donned for over fifteen years. Yet the fabric is not old or found, as often is the case with Yin, but fresh from the factory. We see only torn bits and shreds, cruelly squashed between the steel plating throughout the length of the sculpture. The viewer is hardpressed to imagine how it got there; there are no bolts or weld marks to be seen. Here and there, a zipper or tag protrudes feebly, baring a textual fragment: sizes “M” and “L”; “Made in Hong Kong”; “DOUBLE WIN.”

Modeled on the architectural beams that support traditional Chinese homes, Song Dong’s chopstick is the deep red of the national flag, its twelve wooden or metal pieces of various lengths crafted to resemble certain things, places, and events unique to this city. The rounded tip, titled Bullet, is compact and clean. Inside the other fragments, sculptural surprises await. However, true to Song’s maxim “That left undone goes undone in vain; that which is done is done still in vain; that done in vain must still be done,” his intricate preparations are not quite revealed until one enters the adjoining two rooms: tight, controlled space throughout which all corresponding sections are paired in dizzyingly minimal spatial chaos. At the entrance, one piece of Song’s chopstick is placed vertically; inside, one finds a blood-splattered reflection in a mirror. On the ground nearby, another of his is paved inside to resemble a wide, black asphalt avenue, and in another, miniature camera-laden lampposts return our view. A glance into a fourth reveals small felt facsimiles of the Gate of Heavenly Peace and the Great Hall of the People, and in a fifth, looped video of hands slowly chopping vegetables, one on top of the other. Here, the inhuman meticulousness of the chopping transcends mere allusion to Song’s frequent treatment of food, taking on formal and philosophical significance all its own.

And so on and so forth, the paired visions of their shared hometown of Beijing fill the hall. Song Dong carves out the essence of this marriage, a meditation in twelve parts sculpted from one humongous, banal chopstick, while each section of Yin Xiuzhen’s gazes back unfazed, leaning faithfully next to Song’s or sturdily screwed to the walls above, never too distant, her yin to his yang. Einar Engström