THE XINHAI REVOLUTION MONUMENT: A LONG TIME COMING

| December 6, 2011 | Post In LEAP 11

Under the current set of social circumstances, the need for monuments is as pressing as ever. In Wuhan, birthplace the Xinhai Revolution— the uprising, named for its year in the Chinese calendrical system, which overthrew the Qing Dynasty in 1911— architects and planners think about how to commemorate and look forward.

IN AN AGE where people aspire to overnight fame and selling out is status quo, one could be forgiven for forgetting that we still need monuments. The jagged, chaotic city skyline long ago took their place. Apart from another candidate for “world’s tallest skyscraper,” nothing can pierce its aura as the hallmark of the urban landscape. Culture, history, aesthetics: all these were themselves long ago stripped of their commemorative meaning by architecture and museums as well.

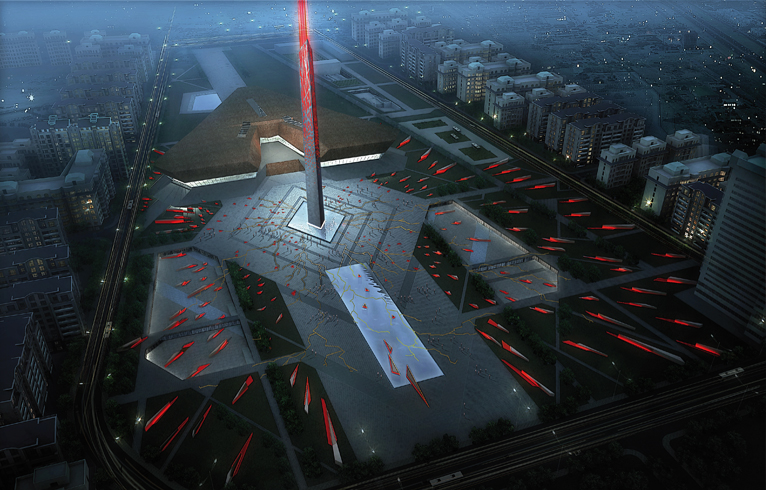

It was in 2008, against this backdrop, that Wuhan announced its decision to erect a monument commemorating the hundredth anniversary of the 1911 Xinhai Revolution. The monument would be placed inside of the main square of the Xinhai Revolutionary Museum, which would be constructed simultaneously at the east end of Wuhan’s first bridge over the Yangtze River. In deciding how to construct the monument, the powers that be went down a route rarely taken nowadays: they put out an open invitation for design submissions from anywhere in the world. They shortly received over 200 suggestions and designs. During the selection process, which saw no government intervention, experts combed through the submissions and selected six designs. The final decision was left in the hands of city residents. The six submissions were placed on public display for ten days in Wuhan’s city planning exhibition hall. Residents could vote for their favorite choice through the mail, online, or at the planning hall itself.

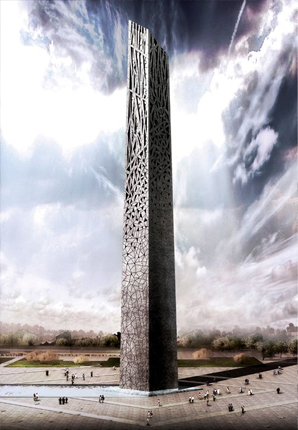

The final choice was an obelisk of over 100 meters, its top lopped off at a slanting, sharp angle. The cramped inside of the monument holds a set of stairs and an elevator, allowing visitors to ascend to a height of about 70 meters and gaze out over the heart of Wuchang District, the Shouyi Cultural District. The structure is built from steel, with intricately carved granite slabs affixed to its exterior. Flocks of tiny triangles wind their way towards the monument’s peak, gradually expanding as they rise, like an arm extended towards the sky. At night, a number of computer-controlled red LED lights shine from the interior with varying intensity, flickering and fading to give the monument the appearance of a lit torch. At the monument’s apex, a cluster of high-powered xenon lamps fire a column of light directly into the sky, transforming it into a sword piercing the night. With the site’s robust design, the LED lights transform what would otherwise be a cold, hard exterior into a resplendent, changing surface. Together with the square in which it sits, the monument appears to be throwing off a shower of sparks, somewhat analagous to the Xinhai Revolution’s place in history as the “one single spark that ignited a roaring flame.”

Wuhan is the geographical heart of China, and one of the most important cities in the country’s interior. Despite that, it has long been the belief of Wuhan residents that their city has not been viewed with the importance it deserves, with a subsequent loss of any number of opportunities for development. From this belief stems their hope that the centennial of the Xinhai Revolution will mark the moment of their city’s revival. This design, more than any of the others selected, was the one that tapped into those feelings. The beam of light from the monument’s tip is a special nod to collective sentiment. It is a pillar of strength pointed towards the sky, a cry to the heavens, a signal of the people of Wuhan’s obstinate desire to cast aside the decay of commercialized construction.

The monument’s designer is the young architect Xu Dongxin. At the time of his entry into the design competition, he had just opened his own architectural design firm. Amidst the scrabble and hardship of setting up his own shop, he came across the Xinhuai Revolutionary Monument’s open call for submissions. The contest’s minimal conditions and prerequisites clinched it: he had just found his firm’s first project.

In the past, constructing any monument to commemorate events of the New-Democratic Revolution— the period between the advent of the May Fourth Movement and the establishment of the People’s Republic— had always been subject to conditions, including those imposed by the public. As a result, designers often chose to use traditional forms drawn from the masses, conveying commemorative concepts through the use of figurative symbolism. Xu Dongxin’s design, however, is geometric, abstract. Through the use of parametric design software, he was able to produce three-dimensional models of his monument, choosing from hundreds of different design possibilities. His design process viewed the monument not as a sculpture, but as an especially meaningful work of architecture. Xu’s focus went beyond the question of how to visually embody the significance of the Xinhai Revolution. To him, the more important question was how a static building likely to remain standing a century or more would influence the frenetic development of the city around it. He wanted his monument to be far-sighted, risk-taking. More than just looking back on Wuhan’s past, he wanted his monument to shape the city’s future. Compared with the fast-talking, forward-thinking, fashionable cities of the south, Wuhan has yet to cast off the burden of its unreconstructed industrial past, though it has long hoped to do so. Both Xu and the people of Wuhan harbored high hopes for the monument. For them, the monument would be a shot of adrenaline to the city’s flatlining urban heart.

The selection of his design changed the arc of Xu Dongxin’s career completely. From that point onward, his design firm found itself spoiled for work, with several projects running at any given time. Wuhan’s design contest proved to be not only an exhibition of the city’s open, democratic side, but a shock to the entire country’s architectural community. Architects have begun to rethink questions of constructing urban landmarks, looking with fresh eyes at monuments’ significance for modern cities. Sometimes it takes an object of no practical value to infect people with profound spiritual feeling; the simpler that object is, the more unique and to the point it is, the more potent the infection.

Change like this brings to mind the Xinhai Revolution itself. It was the most important revolution of China’s modern era, truly the spark that lit the flame. The news of the tragic deaths of its heroes touched off a revolutionary chain-reaction from one end of the country to another. It was a revolution like no other, one that would lay down the pattern for China’s subsequent upheavals. No one could have foreseen the speed at which it would unfold; no one could have predicted the herd instincts of different social classes. Armed with the concepts of the present day, we might deem the Xinhai Revolution an example of “emergence,” a term used in systems theory that is particularly apt here. Revolts sprang up around the country like bamboo shoots from moist earth. Dumbstruck onlookers demanded answers: “Who is in control here? Who is giving the orders? Who knows what comes next?” (Out of Control, Kevin Kelly, 1994). The post-revolutionary “hive mind” sought to re-discover itself, to re-establish the rules of the game. Although the revolution itself failed, it forever put an end to the feudal rule of the Qing court. Thus, the old system of governance passed out of existence. Even if Chinese politics would remain tumultuous in the decades following the revolution, Chinese society would slowly but surely remake itself along new cultural and historical lines.

Although it was originally set for completion this year, by all appearances it would seem that construction on the Xinhai Revolution Monument has been suspended. Word has it that work will resume once the hundredth anniversary celebrations are over, with the finished monument to be unveiled in 2012. But, after all, great things never come easily; just like the Xinhai Revolution itself, the monument’s arrival will have been a long time coming.