CHINA MIGRATION: COLLECTING TANGIBLE CULTURE

| February 16, 2012 | Post In LEAP 12

In 2006, Hong Kong billionaire Joseph Lau purchased an Andy Warhol silkscreen portrait of Mao Zedong for USD 17.4 million at a Christie’s auction. The following year, the real estate tycoon acquired Paul Gauguin’s Te Poipoi for upwards of USD 39 million at a Sotheby’s auction. In 2010, a purportedly Chinese buyer took home Picasso’s Nude, Green Leaves and Bust with a record-setting bid of USD 106.5 million, and at Sotheby’s 2011 spring sale, another Chinese buyer paid over USD 21 million for another Picasso. Statistics like these ultimately may be nothing more than statistics, but in the recent past, a number of acquisitions and exhibitions of Western art in China have prompted contemplation about what it means for the prized possessions of one culture to find themselves in the hands of another.

This question is not new, and gives way to profound meditations on the ownership of cultural heritage. The Elgin Marbles— a collection of sculptures from the Athenian Acropolis that have been housed in the British Museum for nearly 200 years— have fueled heated debate on the topic for almost as long as they have been installed in Bloomsbury. More recently, the whereabouts of Zodiac animal fountainheads originally looted from the Old Summer Palace in Beijing— incidentally, during attacks ordered by the 8th Earl of Elgin, principal signee on the Chinese handover of Hong Kong to Great Britain and son of the very Lord Elgin who had acquired the aforementioned sculptures from the Parthenon— have come to be a great source of nationalist fervor and consternation. In the twenty-first century, the cross-border exchange of cultural relics is more or less regulated by market economy, wherein economic transaction has by default come to substantially augment the cultural value of modern and contemporary art as well.

Within the past year, newer cultural jewels have been departing their motherlands for Asian pastures, as Greater China has played host to a number of exhibitions of mid-to-late twentieth century American and British art: Roy Lichtenstein at Gagosian Hong Kong, John Wesley at de Sarthe Gallery Hong Kong, Alex Katz at James Cohan Gallery in Shanghai, and Peter Blake at the Space, Cat Street Gallery in Hong Kong. Worth noting is that while all these artists are relatively well-known in the Western art world, primarily for their association with the Pop Art movement, in China their names have been less prominent, blotted out by the great, looming shadow of Andy Warhol. Assuming that these gallerists possess reasonable impetus to bring these works to Chinese and Asian collectors, the question is inevitable: why would said collectors be interested in acquiring them?

Did Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol plant the motivational seed for today’s Chinese acquisition of Western art with their visits in the 1980s? Just as any educated Chinese knows of Marco Polo and Matteo Ricci, and of the oft-comparisons between the Chinese and Italian collective consciousness, learned Chinese collectors surely know how Rauschenberg was granted permission to work with the “national secret” of xuan paper in 1980 (see First Person, LEAP 9), as well as of Warhol’s rather privileged travels around the country in 1982. Acceptance of outsiders is often first come, first serve. It may be worth noting that in 1984 Volkswagen was the first foreign automobile manufacturer to enter the Chinese domestic market; today the German company are so favored that not only were they granted the coveted distinction of being the car sponsor for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, they now sell an astounding one million vehicles per year here, far more than any other competitor. And perhaps that’s one theory: though improbable, the allegiance of the Chinese audience to Pop Art could have roots in these fleeting, distant moments of cultural diplomacy.

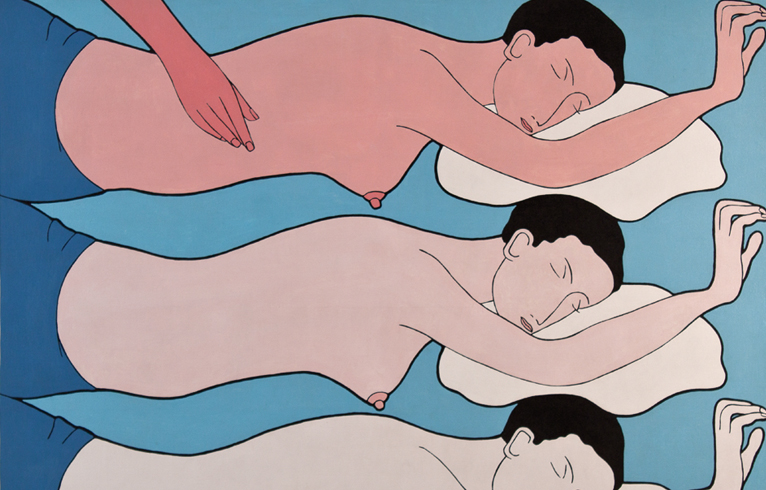

Although the question as to why collector X would collect Pop over this or that movement, or even over Chinese art, surely merits deeper investigations into aesthetics, politics, economy, and even collector X’s personal background, such preliminary assumptions are hard to resist, especially when collector Y and Z are following suit. One still wonders if what drove Japanese collectors (and corporations: The Japanese insurance magnate Yasuo Goto shelled out nearly USD 40 million for Van Gogh’s Still Life: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers in 1987) to fetishize Impressionism in the 1980s transcended the simple desire to own fiscal assets across the globe, especially as, like the China of today, the traditionally jingoist Japan was a rumbling economic tiger on which the rest of the world kept a careful eye. Pascal de Sarthe (of de Sarthe Gallery Hong Kong) points away from economic strategizing and to the parallels between young Chinese contemporary artists of the early 2000s and American Pop artists of the 1960s, stimulated in China by the very colorful, clean designs of Pop’s then-new images of consumerism and the contrast between these and the previous prominence of a simple palette of blue, black and gray. Eventually, the dime-a-dozen artistic reactions to China’s burgeoning capitalism— culprits need not be named— and the subsequent interest in acquiring the paintings and sculptures forged by these reactions, gave way to a more varied creative ecosystem, just as it did in America and the rest of the world thirty years ago. De Sarthe’s own recent solo showing of John Wesley, a key figure in Pop history who has nonetheless long remained in its background, is his attempt at retelling that history. In other words, Wesley is still an artist with huge financial potential, but more importantly, he comprises the other side of the easy, Warholian narrative. Though doubtfully the intent of any Chinese collector, to purchase a Wesley— or until recently, even, the equally undervalued Ed Ruscha— may equate to taking a poignant stance: to state a belief in a historical alternative. If the collection of Pop Art were framed in terms of historical materialism, it would be an act of socialist, Marxist anti-imperialism. Except here, the act involves purchasing the tangible culture heritage of the imperialists themselves.

Of course, a reliable study in collecting tendencies should, again, first take art history into account, or the engagement that a collected work takes with past artworks. That Alex Katz, who broke formal ground with his blown-up facial portraits of New York bohemians in the 1960s and who in early 2011 had a solo exhibition at James Cohan Gallery in Shanghai, left fingerprints on the output of many a contemporary Chinese painter is a rarely disputed contention (see review, LEAP 9). Many Chinese collectors have gotten their start buying Chinese contemporary art, and as many of them dedicate time and research towards acquiring more of this or that artist’s work, it would only seem natural that the collector eventually seek out its older cousins. Like that 2004 Yue Minjun? Why not try a vintage 1970 Katz?

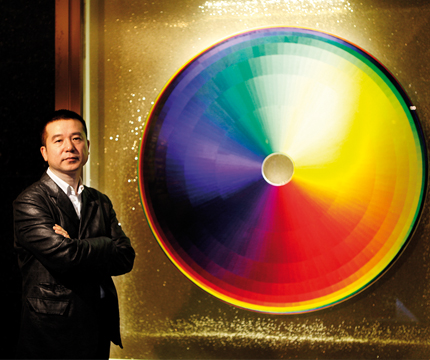

The previously Chinese-only contemporary holdings of Chinese-Indonesian collector Budi Tek have recently taken a Westward turn. Tek’s recent acquisition of a sculpture by American Minimalist Fred Sandback is slated to be shown in a private museum he shall open in Shanghai in 2013, where it is rumored to contain dedicated space for the display of installations by Anselm Kiefer and Bill Viola. Shanghai-based collector Qiao Zhibing is another of the few collectors in China to display non-Chinese art in public; at one of the clubs he owns in Shanghai, works by Olafur Eliasson and Antony Gormley alike are openly visible to any of the club’s patrons. Like collectors anywhere, though, Qiao is concerned with the provenance of an artist. Of all the works in his ever-growing collection, he is most proud of a number of canvases from the “Bucket” series of Chinese painter Zhang Enli (who upon closer inspection shares much in common with the Belgian Luc Tuymans), due in no small part to the fact that the remaining “Bucket” paintings are at the Tate Modern. Recently, though, he has also focused on buying work from international artists, and his collection now boasts creations from Western superstars Adel Abdessemed, Anselm Reyle, Tracey Emin, and Thomas Houseago. For Qiao, there is no sense of cultural ownership gained by acquiring these works. His collecting of foreign art is a “pursuit of wisdom,” albeit one that may carry with it elements of “internationalizing oneself,” even if, as Qiao states, “art knows no borders.” At the same time, Qiao believes that the acquisition of an artwork is an act of fate.

The argument, however, that the migration of Western artworks may dwell in purely spiritual or aesthetic considerations of the buyer may fall flat in the face of another: that the only considerations that matter are those of the seller. In China’s case, the seller has not only tended to be a Westerner, but more and more of these sellers are settling in Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. Supply-side economics posits that demand is a mere consequence of supply. By logic, then, if Gagosian does not show Lichtenstein in Hong Kong, collectors there are much less likely to take an interest in Lichtenstein. The same holds true for James Cohan in Shanghai, Pace in Beijing, Ben Brown in Hong Kong, and will as well for Simon Lee and White Cube, should they open up spaces in Greater China in the near future as is rumored. But supposing that— as is increasingly true in the blurry international biennial-and-fair-driven model of today’s art market— Chinese collectors proactively create this demand for themselves by flying directly to the supply in Basel and at Frieze, many still adhere to the old gallery model by which dealer acts as mentor to collector. Gallerists like Arthur Solway of James Cohan have spent their entire lives in the art world, and it is not outlandish to assume that without their sagely advice and assistance, few collectors would be able to find and secure the art that suits their needs, no matter what ends these needs seek. In this model, the dealer becomes consigliere, educating and advising over years and even decades.

Part of this knowledge is based on value judgment. Hyper-valued Chinese contemporary art also has lead to an increased awareness and acquisition of modern and contemporary Western art, especially as Chinese collectors are just as knowledgeable as their Western counterparts, and are as such unwilling to overpay for any given work— no matter how much it moves them. In great part, the new generation of Chinese collectors demand to see a demonstrably sound career trajectory for an artist before they shell out not inconsiderable sums of hard-earned money for that artist’s artwork; all other things equal, spending USD 1 million for a “hot” painting by an early-career Chinese artist when one could buy two or three paintings by, say, a long-established Abstract Expressionist for the same figure begins to seem like an inexcusably silly breed of speculation.

In the end, Pop Art still sits below Greek sculpture in status, and there is no uproar heard from the West when a Chinese collector purchases a Warhol or a Lichtenstein. Today’s is a globalized economy, where any product can find its way anywhere, provided the money is there. The same holds true for art, and if anybody is going to object to one country’s cultural heritage being grabbed up by the able, rich paws of another, it could only be an artist with a nationalist prejudice. Alas, even if that artist should raise his voice, it will inevitably be drowned out by the cashier’s ring, by the buzzing din in the auction house after the hammer’s fall.