LIU DING: CAPSULES OF CONCEPTS

| April 2, 2012 | Post In LEAP 13

“It is the objective of the artist who is concerned with Conceptual art

to make his work mentally interesting to the spectator, and therefore usually

he would want it to become emotionally dry.”

Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, 1967

Life is full of endless anticipation. Except for blood and flesh, dreams

and anticipation have become everything in life…

The most intimate friends of anticipation are always around: dissatisfaction,

anxiety, fear, illusion, certain hopes and desperation. In the

midst of all this anticipation, dissatisfaction, anxiety, fear, illusion, hope

and desperation, how shall we make it through?…

Let the feeling grow fully.

Eventually, the moment will come!

Liu Ding, Museum and Me, 2011

IN NOVEMBER 2011, I found myself unexpectedly attending Liu Ding’s birthday banquet. There, I had the chance to see the photographs and a summary of my conversation with Liu at Beijing’s Galerie Urs Meile earlier in the year. Strictly speaking, they constituted the “Conversations” component of his “Liu Ding’s Store.” From the dinner table, I carefully drew the photographs and text from their cardboard packaging. Beyond the excerpts in the summary, it is difficult for me to remember exactly what I said during that conversation. According to the rules of the project, the content of the conversation belonged to a collector, who had just purchased or was about to purchase the audio recording. The conversation was completely private, but since I had no way of reclaiming its content, I— the producer of said content— was excluded from its privacy. The selection of interlocutors in Liu’s “Conversations” series suggests that these “conversations” were also expressions of “friendship” and “trust.” Looking back after the passage of some time, our conversation seems to have recorded a phase of mine characterized by complete idealism. Therefore, it is difficult for me to see it as a work of art. I cannot imagine that conversation on display anywhere in someone’s life besides some random neutral space. Just as Roland Barthes said, the “time and space” contained by a photograph are dead. My memory can only capture the context in which our conversation once existed. The transformation of the conversation into a work of art deprived me of the ownership of its contents; now, in revisiting this work of art, I become but a contaminated spectator. The result is an intensity of feeling, the containment of which seems to require complete rationality.

“Intensity” is a word that often appears in the work and thought of Liu Ding. It emphasizes a high density of artistic relevance and intelligence. The price of this kind of speculative creativity, with its delight in achieving intellectual resonance, is precisely the emotional dryness described by Sol LeWitt in his famous essay. This formal and emotional extreme calm is most evident in Liu’s post 2008 work, suggesting that the Internet slander regarding his “creative plagiarism” of April 2008 were a turning point. Liu includes two “gifts” in his new piece, Museum and Me, both of which were previously sent out in real life. One is the wedding gift— a letter— that Liu sent for Hu Fang and Zhang Wei’s wedding during Art Hong Kong; the other is a black and white video of “Marilyn Monroe sings a Happy Birthday song to JFK” that Liu had re-edited and given to a collector. The emotional connection expressed by these gifts, in the context of universal human celebrations such as weddings and birthdays, is easy enough to understand, but Liu Ding adapts contemporary art and the rules of its game to re-encode these protocols of celebration. A letter and a birthday song, leaking out of the realm of private bestowal and into the public sphere, become a kind of emotional currency, one with exchange value. But we cannot completely deny the moment in which a gift is still a gift, and that Liu’s personal feelings and emotions are condensed within these objects at that time.

In his essay on romantic conceptualism,¹ the critic and curator Jörg Heiser mentions the idea of the indexicalization of conceptualism.² Simply put, indexicalization means the abandonment of representation in the work of conceptual artists in order to create an effect with maximally simplified and enriched elements. In pragmatics, the most salient characteristic of indexicalization is context dependence and sensitivity, sometimes to the point of egocentricity. That is to say, the listener (or viewer) must know the time and place of the speaker’s utterance in order to comprehend and interpret its content. In Liu Ding’s art, utterances are sometimes completely impersonal and objective, such as “let’s suppose this is a beginning for discussion,” and “omission is the beginning of history writing” (We tend to become emotionally involved in subject matters that were invented and Omission, 2009). Sometimes, they possess a partly-false, partly-genuine enthusiasm: “In 1987, I saw this black and white print of Matisse’s work, casual, inventive, peaceful, uninhibited. I was enchanted…” (Encountering Matisse Twice, 2009). Sometimes, personal aesthetic experiences are dug up and transformed into pure ideas (Experience and Ideology, 2007). Liu’s gift to the collector alludes to the various desires and feelings that permeate Monroe’s legendary and tragic life. Her decadent singing foreshadows Kennedy’s celebrated but truncated political career. These two characters are both the subjects and sacrifices of power and desire, and as such they leave a great deal of static in the background of a simple, private gift. Liu’s narratives and the context of the museum insofar form an increasingly complex chain of links. ³

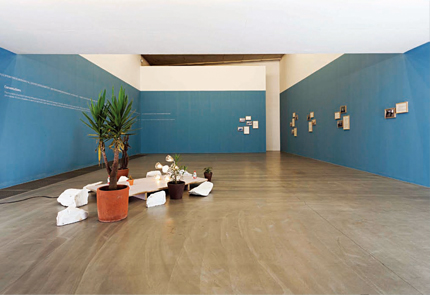

Those who have followed the progress of Liu Ding’s work will note that his early work exhibited a certain inclination toward kitsch. That trend forms a sharp contrast with the formal minimalism and dematerialization of his post-2008 work. It is as if the artist, who once seemed innocent, idealistic, and unafraid to make mistakes, grew up overnight, becoming deliberate, calm, objective, and self-confident. Similarly, Liu’s 2006-2007 series of paintings, “Samples from the Transition—Products” featured canvases produced by workers in Dafen, which were clearly more realistic than the picture planes of “Liu Ding’s Store: Take Home and Make Real the Priceless in Your Heart.” That is to say, the former remains loyal to the tastes of the market and of painting reproduction, as opposed to evolving into an elaborated personal aesthetic. More important than formal changes is that Liu now no longer merely creates artwork; he also creates a context of how his art should be interpreted. He weaves artwork and narratives together to form a precise index system, akin to a circular ring in which head and tail link. But perhaps we have all been misled by the shiny objects and online gossip. In his 2009 solo exhibition at the Primo Marella gallery in Italy, Liu displayed on a single white table 21 small watercolors he painted between 1994 and 2000, titled Sketches in the Garden. The scenes are fresh, clean, simple, and accessible, suggesting a young artist full of zeal and belief in his instincts.

However, professionalization is an unavoidable topic and choice for an artist at a stage like Liu Ding’s. His early, simple passion for art has evolved into a more complicated, rational, and comprehensive intervention and critique of the art apparatus. In “Liu Ding’s Store,” this critique is primarily realized through his initialization of a series of agreements with other creators, participants, observers, collectors, and institutions. But under the conditions of these rational, mutually beneficial agreements, perhaps it is only the yearning for sincere, profound exchange and identification that holds the key to opening Liu’s sealed circle. Spinoza and Deleuze both discussed “affect” as the emphasis of the intensity of relationships between people and objects, or objects and other objects. “Affect” is the state born of the strong affiliations between people’s minds, bodies, and emotions, always manifest as desire, joy, and sorrow. It could be said that Liu creates a tough circulation of values, concepts, and objects for his work, cloaking certain past emotional works and former acquaintances and friends in the garb of rationality, suppressing their emotions and memories. He presents us with a series of solemn, exquisite, and perfectly-wrapped capsules of concepts. If we swallow them with premium mineral water and wine, we will never taste the slightly bitter feelings and scars of time they contain.

1: Jörg Heiser, “Moscow, Romantic, Conceptualism and After,” e-flux journal no. 29, November 2011.

2: Ibid. citing Luis Camnitzer’s distinction between conceptualism and conceptual art at the 1999 exhibition “Global Conceptualism”: “Conceptual art can still be understood as a movement of purist techniques and practices pursued by certain European and North American artists. Conceptualism is used to denote a series of activities in various fields on a global scale. These activities all share a kind of abstract attitude about returning to principles and liberating the production of art from reenactment and material presentation in order to make it a means of communication.”

3: Zhu Zhu, “Multiple Clues: Liu Ding’s Between small gardens and small marketplaces,” from Liu Ding’s Thinking: Between Small Gardens and Small Marketplaces, published by Primo Marella Gallery, Italy.