UNDER THE BIG BLACK SUN: CALIFORNIA ART 1974–1981

| May 10, 2012 | Post In LEAP 14

“Under the Big Black Sun: California Art 1974–1981” (“UBBS”) is a sprawling exhibition that hinges on a bold claim and a stubborn refusal. The claim, made by MOCA chief curator Paul Schimmel, is that the unruly, anything-goes pluralism of California art during this period had far-reaching consequences that are “just beginning to be understood.”¹ America had awoken from the fever dream of the 1960s disillusioned by the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War. But on the West Coast, university arts education was flourishing, market pressure nearly absent, and previously marginalized groups began to take their places at the art table. This combination of elements led to an explosion of artistic experimentation that, according to Schimmel, helped to liberate artists from the shackles of art’s “master narrative of progress and succession” (that toxic parade of isms from New York), paving the way for postmodernism and leading to our current “global” moment. “L.A. is never going to be a real art center unless, in the process, it ceases to be L.A.,” prominent New York critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote dismissively in 1981. Now it turns out that the Great California Freak-Out of the 1970s had been art’s secret Prime Mover all along.

The show’s title comes from a 1982 album by the L.A. punk band X. “UBBS” also suggests a dark side to Schimmel’s everything-under-the-sun inclusion of over 500 works by 139 artists, densely arranged within the Geffen Contemporary’s converted warehouse space. Though much of it is fascinating, there is too much stuff— mostly art, but also posters, flyers and projections of 1970s-era news footage— jammed into the show. “The very messiness of the 1970s,” Schimmel counters, “should not be cleaned up, codified, or organized the way previous art-historical periods have.” This refusal is the exhibition’s double-edged organizing principle.

Nixon’s 1974 resignation speech, seen under glass, glumly welcomes visitors, presented alongside the presidential pardon that safeguarded Nixon but outraged the nation. Opposite these is California Funk artist Robert Arneson’s Portrait of George (1981), a poignant, unselfconsciously ugly ceramic bust of San Francisco mayor George Moscone, assassinated in 1978; the rejected public commission includes a plinth covered in graffiti-like scrawls that intimate details about Moscone’s life and death. Flanking this: muralist Terry Schoonhoven’s panoramic disaster painting Downtown Los Angeles Underwater (1979). The 20-foot-long work is covered in a translucent scrim to create a submarine view in which the city center’s newly completed skyscrapers tilt alarmingly sideways, abandoned to the fish. The painting suggests not only the ever-present seismic anxiety that accompanies West Coast fault-line living; its apocalyptic grandeur reflects a time when it felt as if the world might be ending. Bringing together California’s north and south, the political realities and darkening sentiment of the period, Schimmel creates a terrific point of departure for those setting out on the exhibition’s epic journey.

Hollywood functions in “UBBS” as a generator of images and forms ripe for plucking. William Leavitt’s The Impossible (1980), part of an obviously fake rock wall adorned with a broken manacle, is a film-set fragment constructed for a nonexistent movie, appearing as if the logic of Cindy Sherman’s contemporaneous “Untitled Film Stills” had shifted from the figure to the background. In Leavitt’s work, the objects used to construct the spaces of cinema have snapped their chains, leaving viewers to imagine their scripts. David Lamelas’ troubling, magnetic video, The Desert People (1974), combines the stylistic conventions of a Hollywood road movie with a pseudo-documentary about Native Americans. Each time we think we know where we stand, the line between fact and fiction shifts. John Baldessari’s 1981 Virtues and Vices (for Giotto) re-imagines a fourteenth-century fresco by pairing each of the fourteen requisite terms (“Envy,” “Pride,” and so on) with a black-and-white film still. Using the staged quality of the pictures to undermine whatever moral weight the words have, the work alternately suggests how such images might encode, encourage, or inhibit behavior.

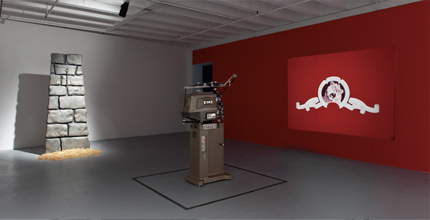

In Jack Goldstein’s nearby film loop Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1975), the iconic tiger that appears at the beginning of the studio’s films floats atop a lurid red backdrop, trapping the viewer in an endlessly roaring prelude to an unknown film that never begins. We are left to fixate on this usually ignored gateway moment, which Goldstein further estranges by desynchronizing sound and image. That Goldstein’s films are usually associated with the New York art scene is not lost on Schimmel, who writes, “What cohered as postmodernism during the 1980s in New York effectively codified ideas and concepts evolving from art made in California between 1974 and 1981.” In fact, Goldstein is one of several artists featured in “UBBS” who studied with Baldessari at the California Institute of the Arts’ newly established post-studio program before leaving for New York; others include David Salle, James Welling and Matt Mullican. Here Schimmel makes a strong case, not for replacing one origin myth with another, but for looking more carefully at the fruitful bilateral exchange that was occurring between both coasts.

“UBBS” also presents foundational early works by well-known artists. The Little Girl’s Room (1980) is Mike Kelley’s first installation work. It uses sculptures, lighting and wall-hung work to tell the story of a girl entering adolescence who has responded to a sexually-charged nightmare by redecorating her once-flowery bedroom with geometric, Minimalist-inspired artworks that glow eerily within the now black-lit space. The work is remarkable for its ability to usher viewers into a labyrinthine, tangible dreamwork; it also signals the beginning of a long-term exploration so particular to Kelley, one that linked young adulthood, psychological trauma and the built environment.

A number of the most compelling projects resist classification. Bonnie Ora Sherk’s Crossroads Community (The Farm) (1974-1980) transformed seven acres of traffic islands in San Francisco into a functional urban farm and “life-scale and social artwork.” (Following Schimmel: Is The Farm a precursor to Rirkrit Tiravanija’s The Land? (see LEAP 8) ) Artist Lynn Hershman initiated The Floating Museum (1975-78), a platform through which she and her collaborators could, as she writes, “recycle existing spaces and resources as well as to transform local areas into temporary exhibition sites,” including “rural landscapes, public buildings, city streets, prison courtyards, [and] non space such as air and sound waves.” Back then, art was life and life was productive.

Elsewhere: Experiments in photography, such as Robert Heinecken’s ghostly, blurred images of Reagan’s inaugural address (the cut-off date for the exhibition’s timespan), made by pressing photographic paper against a television screen; political posters for various leftist causes by Rubert García and Malaquías Montoya enlisting the pared down, colorful language of Pop in the service of social justice; proof of punk rock’s animating force— Raymond Pettibon’s illustrated flyers for the band Black Flag, brimming with sardonic references to the shredded social fabric (note to Schimmel: here less would have been more— each one is so interesting); feminist art, such as Judy Chicago’s Female Rejection Quintet (1974), color abstractions based on “vaginal forms” paired with delicately hand-written texts about Chicago’s struggles for acceptance.

“I am talking here about a time when I began to doubt the premises of all the stories I had ever told myself,” Joan Didion famously wrote from Southern California as the 1960s shuddered to a disorienting halt. “I was meant to know the plot, but all I knew was what I saw: flash pictures in variable sequence, images with no ‘meaning’ beyond their temporary arrangement, not a movie but a cutting room experience.” Visitors to “UBBS” who were expecting a made-for-TV movie might have been disappointed, but those of us unafraid to root through the cutting room piles left the show both exhausted and innervated. The takeaway is not another art historical narrative, but a whole new constellation of references from which to draw, stills we will continue rearranging for the foreseeable future. David Spalding

1 All Paul Schimmel quotations come from his essay in the exhibition’s resource-rich catalogue.