A FUNCTIONAL INSTRUMENT: CULTURE AS POWER

| June 20, 2012 | Post In LEAP 15

In 1942, Mao Zedong spoke to the encampment of a burgeoning Communist Party of China in Shaanxi province, in what would later be heralded as the “Yan’an Talks on Literature and Art.” At the time, the American scholar Joseph Nye was five years old. Half a century would pass before he, as dean of Harvard’s Kennedy School, would coin the term soft power: the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion and payment. Like many Western imports, the concept arrived in Beijing with a lag and a twist.

When President Hu Jintao addressed the 17th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2007, he announced the key national strategy of increasing China’s soft power. According to the government news agency Xinhua, one priority of the directive was “to vigorously develop the cultural industry, launch major projects to lead the industry as a whole, speed up the development of cultural industry bases and clusters of cultural industries with regional features, nurture key enterprises and strategic investors, create a thriving cultural market and enhance the industry’s international competitiveness.”

Noteworthy here was the focus on the notion, perhaps another late import, that in political discourse here did not exist until the early 2000s: the transformation of “culture” into “cultural industry.” But beyond this, the core ideals Hu spelled out remained no different from 70 years ago, when Mao Zedong gave his “Yan’an Talks.” Then already astute enough to realize the persuasive qualities of poetry and painting, his midnight address swiftly spelled out the terms by which art would be employed for the next several decades in China, carving out for it a clear epistemological and aesthetic niche. First and foremost, he called upon art to serve the people, the workers, peasants, and soldiers. More specifically: “What we demand is the unity of politics and art, the unity of content and form, the unity of revolutionary political content and the highest possible perfection of artistic form. Works of art which lack artistic quality, have no force, however progressive they are politically. Therefore, we oppose both works of art with a wrong political viewpoint and the tendency towards the ‘poster and slogan style’ which is correct in political viewpoint but lacking in artistic power.”

This structural framework, which would actually most often materialize in the convenient— easily created, transported, and understood by all— form of the poster, achieved its aims, helping the official line hold sway not only over ideology, but also over artistic delineations. Revolutionary Realism, and later, Soviet-style Social Realism, became the unshakable core of the arts in China. The Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956 would buttress the means and ends to the prevailing doctrine. “Letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend” amounted to the state-sanctioned exhibition of foreign art for an entire year, including shows of British, Mexican, Vietnamese, Italian, and Greek art. Yet this introduction of foreign artists and movements was intended to reveal that which was “incorrect,” subject it to the appropriate rebuke, and thus bolster the existing aesthetic criteria, as well as the people’s appreciation of said criteria.

The above-mentioned campaigns and policies, as well as many that would follow, were engineered for an insular state, unconcerned with the outside’s perception of the nation. This attitude changed, of course, with Opening and Reform. The overarching implications of free-market liberalization brought two things to the Chinese people: one, exposure to contemporary culture outside of China; and two, new realms in which people could begin to build their own lives, to, as it were, choose their own adventures.

For most of the next decade— excepting the short-lived Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign of 1983-84— contemporary art flourished, and policy tended to accommodate. Rather, vague and open-ended regulations allowed enough elbow room for artists to explore virgin ground, for them to come into contact with both the real and art historical outside worlds. Previous bans on interaction with foreigners, for example, became lax to the extent of allowing “informal contact,” and foreign salons, private exhibitions, and underground concerts were duly given the blind eye. All in all, the freer dimensions of the 1980s could be contributed to newfound teleological possibilities, and the need to identify the Chinese nation and the individual on the global stage became a pressing endeavor.

A NOD TO CHINESENESS

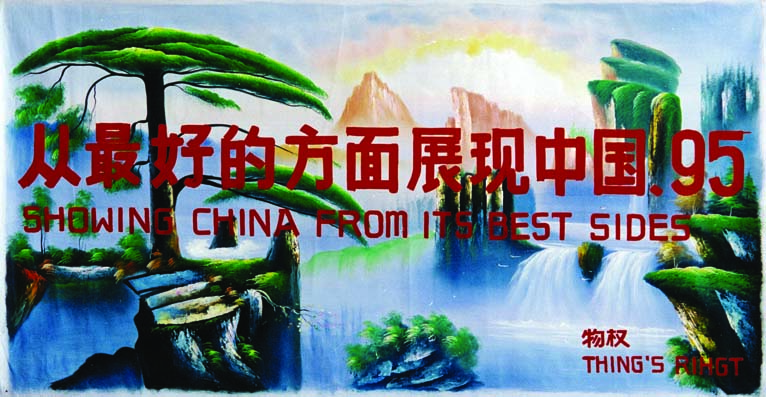

FROM 1989 ONWARD, the perception of contemporary art as a plausible route for commerce began to find initial formulations. Critic, curator, and artist Colin Chinnery points not to a change in official government policy but to a change in people’s mentality. “People became much more pragmatic. Rather than the intangible and the sublime, they [artists] wanted to tap into something much more concrete, and that concreteness was attention, differentness— Chineseness.”

Presumably, this notion of Chineseness— especially when framed in the picture planes of Political Pop, which could harmlessly espouse Soviet aesthetics as well as iconic red imagery— would have equated a friendly compromise between content and form well enough to garner official tolerance, at the very least. It might be said that Wang Guangyi was the first to capitalize on this balance, at least in terms of its economic potential, without a major sacrifice of artistic integrity. On the one hand, the reenactment of Western art history was giving way to fresh movements of Political Pop and Cynical Realism, thus contributing to the academic foundations of China’s own contemporary art history, and on the other, Western collectors drooled for the stuff. It was the start of a new arm of soft power, and more or less a win-win situation. Yet it would still take some time for officials to broker a diplomatic wormhole between two opposing worlds.

“At one point there was a compromise. That somebody like Fan Di’an would be assigned to the Central Academy of Fine Arts— and when he left there, to the National Art Museum of China, and later on, as curator of the China Pavilion of the Venice Biennale— is significant for many reasons,” says Director of the Instituto Cervantes Inma González Puy, who has been active in many a cultural sphere in Beijing since she began working at the Spanish embassy in the early 1980s. “The government began to seek out those who were moderate but in touch with the art world— as official as they were alternative. This was very important strategically. They started to do this at the end of the 1990s and the early 2000s. They looked for key people to connect the two mediums. There was this dichotomy, the question of how to turn the vanguard of the 1980s and 90s into ‘official’ art. It was an intelligent move.”

Apparently so: Uli Sigg, by many accounts the most renowned collector of Chinese contemporary art in the world, states that the most significant change he has noticed in the use of contemporary art as a tool for exchange over the last 25 years is “that the list of artists in official exhibition has been enlarged beyond the official oil painters association members and academic staff, and therefore there is a potential to exhibit Chinese contemporary art in a more representative way if the officially installed curators are able and willing to exploit this potential.”

Puy recalls the moment when the dichotomy first began to visibly wane: “Official acknowledgement of contemporary art became apparent during the Year of China in France, in 2003. Fan Di’an was curator of an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou [‘Alors, La Chine?’].”

For the two decades preceding this González Puy herself, like many other foreigners of certain status, had already been involved in the organization of exhibitions and cultural events both abroad and in Beijing. In the late 1980s and early 90s, even, she hosted an exhibition of a young Zhang Xiaogang’s paintings in her own apartment; arranged screenings of the filmmaker Zhang Yuan’s first movie Mama in the Sheraton; and brought the works of no less than 35 artists to Barcelona for the exhibition “Des del País del Centre: avantguardes artístiques xineses” (From the Middle Kingdom: avant-garde Chinese artists).

Public and private spectacles like these were commonplace at the time, and while in hindsight they were crucial to the forward movement of the Chinese scene, they engendered pigeonholing. Director of the Italian Cultural Institute Tang Di, who participated behind-the-scenes in a number of now-historical art happenings, sympathizes with the artists: “The thoughts and ideas they believed were unique— in effect their artistry— were briskly taken by the Western system and critics and tossed in together under one umbrella symbol: Chineseness. It couldn’t be avoided, of course, as one person inherently understands another from his or her own knowledge system and worldview.” Hence Hu Jintao’s call to raise soft power— ergo, to entice the rest of the world into seeing China through the prism of its own native rhetoric— on the cusp of the 2008 Olympics in Beijing.

Director of Goethe-Institut China Michael Kahn-Ackermann— who, having arrived in Beijing in 1975, in the 1980s was already generating Chinese soft power in his private time by translating the literary works of Wang Shuo, Zhang Jie, and Mo Yan into German— was also involved in the outward push of Chinese contemporary art when he was living in the now-defunct artist community of Yuanmingyuan and surreptitiously helping arrange shows locally for artist-neighbors such as Lü Shengzhong. Often organized in conjunction with one of Chinese contemporary’s greatest ambassadors, Hans van Dijk— who would go on to found the China Art and Archives Warehouse with two of the others, Ai Weiwei and Frank Uytterhaegen— these exhibitions would offer the up-and-coming the chance to peddle their paintings to wealthy expatriates. With each canvas sold, the future of this cultural industry grew that much more luminous.

Kahn-Ackermann recalls that outside these private gatherings, attitudes remained indecipherable. He had organized an exhibition of the German neo-Expressionist Jörg Immendorff in Beijing in 1993, that up until the very last minute no venue was willing to host—ultimately, they had to mount the exhibition in a random hotel in the Wangfujing area. In the same year, however, the government had allowed Achille Bonito Oliva to parade the work of 14 artists at the 45th Venice Biennale. Why the discrepancy? The most likely explanation might be that there is no explanation.

TRICKLE-DOWN?

PERHAPS CONTEMPORARY ART just isn’t high enough on the list of priorities, and the push for soft power is directed elsewhere. At a symposium on Chinese cultural policy in Beijing this past May, which saw the participation of academics and experts from a variety of fields, a spokesperson from the Bureau of External Cultural Relations of the Ministry of Culture opened his lecture by rattling off an impressive round of statistics. The Bureau maintains cultural exchange agreements with 145 countries, organizes an annual 800 exchange plans, and to date has “exchanged” with over 1,000 organizations globally. At present, nine Chinese cultural centers are already open abroad, four are awaiting construction, and thirty-plus countries are in negotiations for the same— figures that don’t include the Confucius Institute, which within five years of its 2004 inception had already spawned over 300 branches worldwide. Generally speaking, official priorities are leveraged on the same old card of Chineseness: Confucius Institutes focus on language teaching; art focuses on traditional ink painting; and the performing arts, on what else but kung fu— one particular opera has been kept on tour for over 4,600 iterations because of its “excellent economic performance.”

In spite of— or thanks to— contemporary art’s ambiguous status in Chinese cultural policy, the latter’s encouragement of the marketization of general culture has, since at least 1993, been an overwhelming success: the outflow of artistic practices in China has engendered economic growth in the form of education, exhibition, project outsourcing, galleries, creative industry parks, media reportage, construction projects, and so on. Loosely imagining this trickle-down effect, perhaps millions of people have been liberated from potential poverty thanks to neoliberal stances on the contemporary art industry. Or have they? As bluntly summed up by a professor from Tsinghua University at the same symposium, the liberated are still very few in number: “Culture is still a small-scale activity performed by an elite group. It is a functional instrument. It can get you a car, a house, and a beautiful wife.”

Such a perspicacious definition has us wondering if Joseph Nye’s newest concept— that of “smart power”— arrived in Beijing before it did Cambridge.