CULTURE SHOCK: AMERICAN PAINTING IN CHINA, 1981

| June 26, 2012 | Post In LEAP 15

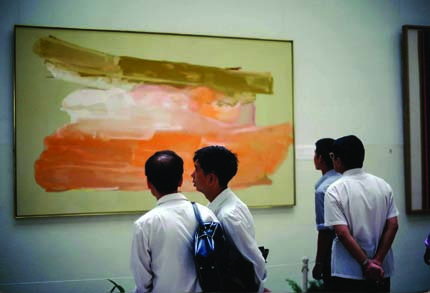

THE BOSTON EXHIBITION— 12 abstract paintings, in context with 58 figurative paintings showing 200 years of American art— jolted the Chinese public and artists out of the Soviet and Socialist Realism then permeating the academies in the period following the Cultural Revolution. The artists had no frame of reference to absorb these new art forms, yet thoughtful and inquisitive as they were— moreover, hungry for information from the West— the exhibition changed their way of thinking, and led to experimentation in many directions.

Shi Yong, an installation artist in Shanghai, described the impact: “For people who lived in isolation for so long, even a small crack would ignite great passion… Modernism and Picasso were basically everything we knew. Hence, I was stunned when seeing the show and could not truly grasp it. It was totally beyond the system we knew.”

But, back then, if you had asked any of the organizers— either Boston Museum curators or U.S. Government officials— if they could have anticipated such an overwhelming response to a survey of American paintings, they would have been modest in their replies. On the other hand, they were committed to showing abstract contemporary paintings, and fought for them when objections were raised.

The West was as cut off from China as China was isolated from the West during the years of the Cultural Revolution. Although “China watchers” in Hong Kong— U.S. State Department officers and major journalists— scoured every newspaper and radio broadcast for the slightest change in political rhetoric and for breaking news from the Mainland, they rarely detected internal art developments. Only a few major exhibitions— mostly ones closed down by the police— made it into the Western press and onto the desks of American diplomats involved with China back in Washington.

In fall 1979 the now-legendary Stars Group hung their paintings on the outside railings of the National Art Museum of China when they were denied a show inside. Two days later the works were torn down. At the same time, Yuan Yunsheng’s provocative mural Song of Life was installed with others at the Beijing International Airport. Depicting a water festival of the Dai people that included two female nudes, it sparked a contentious debate about nudity in public art. When the mural was boarded over by authorities in 1981, this controversy again crossed diplomatic desks.

It was against this backdrop that the U.S. Department of State signed a cultural agreement with China at the time of normalization of relations in 1979, which among its three dozen items called for an exchange of art exhibitions. In an early gesture toward formal relations, the Chinese sent the blockbuster “Exhibition of Archeological Finds” to the United States, which opened at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. in the fall of 1974, toured to Kansas City’s Nelson–Atkins Museum, and closed nine months later at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco to enthusiastic crowds willing to wait eight hours in lines circling Golden Gate Park. Thus, by 1981, the American side wanted to reciprocate with a comparable and compelling exhibition in China. 1

Early discussions among officials responsible for the Department’s public diplomacy considered archeological material and American Indian art, but these were dismissed in favor of a broader view of contemporary American culture. Letters went out to select China scholars, such as Wilma Fairbank, a historian of Chinese art and architecture who also was married to renowned China scholar and Harvard professor John King Fairbank; they spent much of the 1930s and early 40s together in China. She administered a pioneering program of cultural exchanges with China for the State Department beginning in 1942. Fairbank confirmed that a broad survey of American painting, including the most contemporary works, would be a major contribution to a generation deprived of knowledge from the West.

What would “tell America’s story” and best convey the free expression of the individual artist in our society? Hoping to inspire the Chinese artists and public, American diplomats familiar with the crackdown of the previous decade were keen to include a large portion of contemporary art. It was no oversight that abstraction might impress on the Chinese visitors the artist’s freedom of creative expression.

BRINGING BOSTON TO BEIJING

IN 1981, WHEN the curators of the MFA were asked by the public diplomacy division of the Department of State to organize an exhibition from the museum’s collection as the first official American painting show in China since the 1940s, they had very little idea of how the audience would react to these foreign works. Moreover, until recently they had no idea how enormous an impression this exhibition would make on the artists and on the thousands who saw the show.

The museum curators were given complete authority to select the works in the exhibition, sending a message that the U.S. Government respected private institutions and that art professionals would make the artistic choices on quality. Diplomats discussed the sensitivities of nudity, but did not prohibit them, and made the museum aware of potential issues involved with modernism and pure abstraction, yet encouraged the museum to include the best contemporary works they had up through their strong holdings of Color Field painting. (Unfortunately, the Boston Museum had no Pop art, so some examples were illustrated in the catalogue. In addition, images of realist Andrew Wyeth and photo-realist Richard Estes appeared in the catalogue essay, as did “wrap” artist Christo’s seminal 1976 project-piece Running Fence.)

Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., lead curator for the exhibition and head of American painting at the MFA, now curator at Harvard University Art Museums, described the challenge of organizing the exhibition. “We wanted to give them a good survey of American painting and modern works. We had a sense that the modern works were important…We didn’t really know what the Chinese would like, but hoped to find something that would resonate.”

Jan Fontein, then director of the MFA, and an Asian art scholar himself, spearheaded the exhibition, yet even he had sparse knowledge of the Chinese audience and how they might respond. Boston’s long history with the Far East and their collection provided an excellent foundation for the organizing institution; members of the Asian Art Department conferred and participated as well in the production of the show.

Carol Troyen, the young assistant curator of American Art, states, “We wanted to represent Boston, a survey of American painting through Boston eyes and Boston taste… We knew that we were sending one version of the story, but we were very proud of ours. We held nothing back and sent our best works, like our only Franz Kline and Jackson Pollock.

“I remember some concern about Sargent, he was the painter of the upper classes; we wondered how that would go over. We selected one that was not terribly aristocratic-looking (Edith, Lady Playfair).” As it turns out, the Sargent portrait brought attention for its brilliant technique, especially from artists studying oil painting, rather than for its subject matter. Noted critic and professor at the Chinese National Academy of the Arts Shui Tianzhong compared the techniques of Sargent and the work of China’s first oil painter Li Tiefu, “He mentioned that he used to learn from Sargent. At the exhibition, it was the first time I saw his teacher’s work, and I tried to make a connection.”

PRECEDENTS

THE EXHIBITION “Original American Paintings from the Boston Museum” was the second Western painting show presented in China after the Cultural Revolution. The French were first, as one might expect from the masters of “art politique” in foreign affairs.“19th-Century French Rural Rustic Landscapes” preceded it in January 1978, also staged at the National Art Museum of China, drawing crowds in the hundreds of thousands. Although mostly landscapes from the Barbizon painters and earlier, the organizers managed to include a few Impressionists like Monet and Pissarro. 1978 also marked the start of several publications on Western art in China, World Art and The Review of Foreign Art, which became the main source of information and images in reproduction at the time. Naturally, any foreign catalogues and slides were readily savored in the academies.

Unsurprisingly, then, the Boston exhibition drew more than 250,000 visitors during its one-month showing in Beijing in September of 1981, and a subsequent month at the Shanghai Museum from October to November. For the generation of artists just starting their careers, this exhibition has never been forgotten, and still stimulates memories of their first encounters with American artists and modern styles of painting.

The curators picked 70 paintings, beginning with a strong tradition of portraits, history and genre paintings: masterful examples by Sargent and Copley of wealthy Boston society figures, landscape paintings from Hudson River School and Luminist artists, notables George Inness and Winslow Homer (on the catalogue cover and poster), Whistler and Prendergast, early twentieth-century American Modernism by Marsden Hartley and John Marin, plus approximately one dozen contemporary works, including abstract paintings from Abstract Expressionist masters Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Hans Hoffmann, Adolph Gottlieb, and Color Field painters Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and Olitski, among others.

REMEMBERING IMPRESSIONS

ARTISTS, CRITICS, AND curators each saw the works on display through a different lens, and singled out specific artists who made lasting impressions on them. The most curious were hurled into a different world by the Boston show— stunned at first, but eager to absorb as much as they could from these new sources of energy.

Reaction to the show split into two groups. Many of the realist-trained oil painters were captivated by the non-Soviet technique of the paintings in the first part of the exhibition, while the abstract works perplexed them. The second group, although also without any true framework for understanding the abstract paintings, were startled but mesmerized by them. It stimulated them to think outside of their current work. Many of them went on to become experimental artists in their own right.

The prominent painter and conceptual artist Zhou Tiehai appreciated both the earlier classical works as well as the abstract paintings. He was only 15 at the time and in middle school, but found a way to see the show. “The surprising paintings were those like the Pollock and Kline, but the early paintings were quite traditional. I thought the Sargent painting was very well painted, and I liked it very much, on the other side I liked Pollock. For technique, I like Sargent, but for the mind I think I like Pollock.”

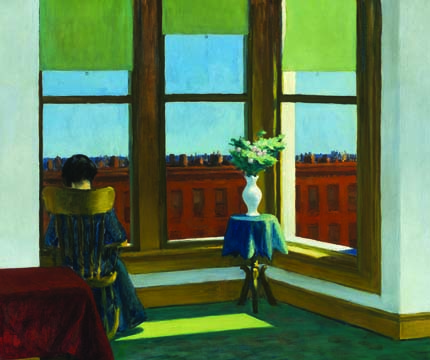

Known for the earliest video work in China, Zhang Peili was only a sophomore in college at the time of the Boston show. Of all the works, he found the Hopper painting A Room in Brooklyn “the most impressive.” In his own early figure paintings of the 1980s, Zhang paints various individuals in isolation— which reiterate the feeling of loneliness that he recognized in Hopper. Zhang also appreciated the narrative or cinematic qualities of Hopper’s images, coming from his own lifetime love of movies. His observations anticipate his later interest in video starting in 1988.

“When I saw Hopper’s work, I thought his style was intricately related with that of post-Impressionism. But his work also contained narrative elements that were not featured in post-Impressionism. His use of colors was highly subjective and intense. Moreover, he emphasized the sense of light. His spatial relationship was somewhat ambiguous between two-dimensional and three-dimensional. A strong sense of American style could be perceived in his work, highly different from the style of European painters… It gave out a sense of jazz music. It was somewhat between reality and non-reality. It felt quite bold.”

Elsewhere, the masterful technique of John Singleton Copley’s Mrs. Skinner and John Singer Sargent’s Edith, Lady Playfair impressed many artists studying oil painting. A large group of artists attending a conference in Beijing were invited by the Boston Museum and American Embassy to preview the exhibition before the public. Excited to see the originals, the artists ran between the paintings closely examining how the works were painted. They carefully studied the Copley and Sargent, then gathered around the Jackson Pollock drip painting Number 10, 1949 to stare in wonderment at the surface, which included a cigarette butt and hairpin imbedded in the “all-over” skein of paint. They also stopped in front of the all-white but textured Jules Olitski painting, pondering how he had applied the paint to the canvas.

The installation artist Shi Yong was drawn in particular to the abstract paintings, especially Morris Louis and Hans Hofmann, on whom he wrote his graduate thesis. “I majored in design. Maybe that is why I was more inclined to accept so-called formalism. It was not included in our system, but I found it impressive. It is highly different. I saw it as something different than realism. Though I couldn’t fully understand it back then, I was stunned… The influence of the Boston show… lies in the fact that it showed us the possibility to open up the previous system. Later I started to do some experimental work, and installations as well as videos. But I didn’t directly imitate any work I saw at the Boston show. Its influence was major on the conceptual level.”

The biggest advocate for the avant-garde artists in China since the 1980s, critic Li Xianting, was particularly moved by the Pollock painting, and drew comparisons with Chinese ink painting. “I almost entered a state of unconsciousness. Chinese art always placed an emphasis on consciousness and political stance. With abstract art, people could freely express their emotions. However, traditional Chinese literati painting was quite close to Western modernism. It was more casual and open-minded.”

For Zhang Wei, a member of the earliest avant-garde “No Name” group in Beijing and one of the first wave of practitioners to exhibit abroad, the Boston exhibition “hit like a bomb, a shock.”

“I was dreaming about blowing up a little corner of Chinese traditional brush painting, to cut off a part and blow it up, that was my thinking— to try and create my own abstract paintings. But when I saw Kline, and all those like Louis, like Frankenthaler, they really showed me the way how to become an artist.”

NEW THINGS, NEW AIR

IT MUST BE acknowledged that the Boston show was only one of several happenings to leave its traces on China and its artists. “The Armand Hammer Collection: Five Centuries of Masterpieces” showed in Beijing just one year later, and Robert Rauschenberg’s ROCI exhibition in 1985 has been regularly cited as a pivotal moment for art diplomacy by both artists and academics. “Original American Paintings from the Boston Museum” is particularly noteworthy for its startling introduction of the new— Western ideas and painting styles, especially abstraction— to an uninitiated public; it opened the window to a different world and has left lasting effects on artists, curators, and critics alike. For the U.S. diplomats it stands out as one of the greatest triumphs in cultural diplomacy in decades. One might draw an apt comparison between the Boston show in China of 1981 and the Armory Show of 1913, which introduced “modern” European art to the United States for the first time. In his historical essay for the Boston catalogue, Stebbins wrote:

After this point [the Armory Show], once Americans had been introduced to the new movements, our painting could never be the same. The world had simply changed too rapidly, and conventional thought of all kind had been shown to be old-fashioned… They tried over the next decades to reconcile modernism— that is, the new attitudes towards art and its content— with their inherent conservatism in visual matters and their continuing desire to represent American subjects and places in their paintings.

Thirty years on after the Boston show, one cannot avoid considering the ripple effect of this one exhibition on Chinese contemporary art’s reconciliation with its own art history. As Gao Minglu summed up the impact of the exhibition of 1981, “The exhibition was a symbol and brought a kind of enlightenment into our world; it brought new things, new air into the Chinese art world.” (Copyright: Meredith Palmer, 2012)