KEREN CYTTER: ANXIETY AS AN ARTISTIC TOOL

| August 9, 2012 | Post In LEAP 15

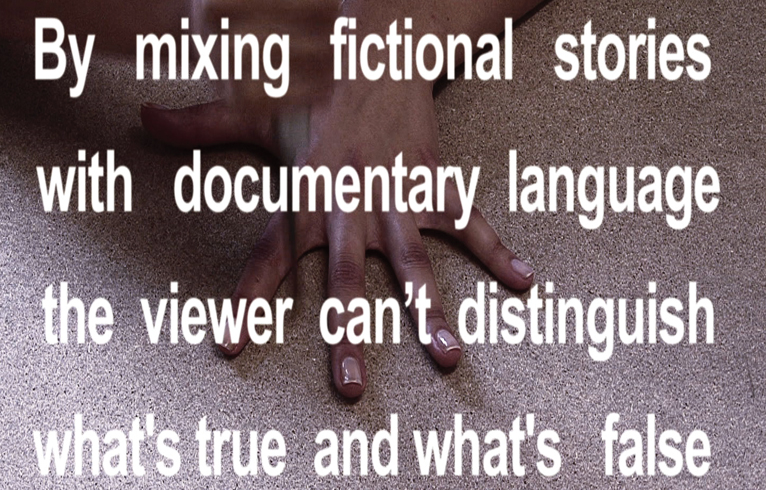

In her work, Keren Cytter is an “offspring” of Bertolt Brecht. She injects the sensation of alienation into the textual narrative of her pieces, breaking up the audience’s experience with subtle tricks and slights of hand. The strange voice-overs of Video Art Manual are a reminder to the viewer of the role of subtitles; the pace and rhythm of the over-dubbing in Brush, cold and stiff, is a little off, not quite keeping with the movements and shapes formed by the actor’s mouth. In the widely discussed Der Spiegel, the actors exchange rapid-fire words, as if participating in an elocutionary relay. Cytter’s greatest skill lies in her ability to stretch a singular narrative into a complex lattice of interwoven sub-narratives, so that text and story dismantle one another: stories within stories become inextricable components of textual form, and Cytter happily takes that textual form and reinforces it as an essential component of the story. In Four Seasons, a woman goes over to complain about the noise her male neighbor, a stranger, is making. Simultaneously, in an alternate and overlapping time and space, she is the same man’s murder victim. Here, an extreme murder scenario and an everyday exchange have been woven together through a doubly-or perhaps multi-angled narrative approach.

But even more importantly, these refined techniques have not been separated from the needs of the film itself. Passion, anxiety, and the shadow of death all move through Cytter’s films, which never part with these ever-present elements. Yet Cytter has no intention of magnifying them within the main body of the narrative, or of making them psychologically acceptable; nor has she cast a shadow of narcissism upon us. Cytter’s take on the world is extremely personal and poetic, but it is also part of a larger discussion of “truth”— which ultimately determines the inevitable intersection between her creations and contemporary art. In Brush, Cytter focuses on a golden comb as a symbol for a man and woman’s love. A story laid out in six parts, this hour-long film features dialogue between the male and female protagonists that often manifests itself as two mutually unintelligible monologues. It is as if the two are lovers in the dark, feeling out but unable to make contact. All that is left is the single brush, bracing their love from collapse. In Brush, love loses its essence and is degraded to a bottomless symbol, a road of temptation stretching infinitely into the distance with no final destination. Any truth— whether in terms of an event, an evolution of text, or even the loss of narrative theme— loses its meaning against this nihilistic backdrop, just as if that hairbrush has concentrated every inkling of attention within the material grasp of its bristles.

The topics that Cytter explores are what we would typically call challenges to capitalist ideology. The preface to Video Art Manual is an imminent power blackout caused by a solar storm, and the finale is the image of a duck-shaped telephone that serves to sustain human communication. Between unfolds the state of an information society, of an entertainment society. “Imminent” becomes the keyword; in an “imminent” world, all truth confronts the possibility of losing effectiveness. Like drug addicts, we are lured to existence by that which has never existed. This is the most effective weapon produced by capitalist ideology. Contrary to the Christian “Good Friday” model, meaning is not decided by previous events, and time is not awarded the essence of truth by the hand of these events either. Our survival is pulled from times of redemption, from history. As it is said in the film, we are living inside of “a kind of romanticized memory made possible by the loss of language.” Aside from her familiarity with form and technique, is Crytter, as the creator, perhaps also aware that spiritual production faces a similar crisis? Su Wei (Translated by Katy Pinke)