STOP-AND-GO: SOUND ART IN MAINLAND CHINA

| September 16, 2012 | Post In LEAP 16

In China, the development of sound art stretches back 15 years (from another perspective, we could perhaps adjust this figure to 12 years; see below). This, in spite of the fact that sound art still occupies a misunderstood and marginalized position (in this respect, media art isn’t much different). However, there are already enough people, happenings, and works to merit a serious historical evaluation— to be sure, it is about time for a more thorough exhibition and canonization of the genre. Here in this article, time constraints and limited print space have lead us to focus only on certain, carefully selected highlights, and assemble an understanding of these from within the framework of art and culture. The texts presented here have been selected on the basis that, rather than claiming that Chinese sound art has developed uninterrupted over the last ten years, assert that its development has been a stop-and-go process, and that every time the gears again get going, the impetus has been driven by the influence of the outside, of people of varying backgrounds who ruptured the prevalent anticipations of the time. Only by drawing attention to this reality may we ourselves rupture the foolishness over who was first or who was avant-garde, and genuinely immerse ourselves among the veins of sound art and art history.

“SOUND” AND “SOUND 2”: THE CONCEPTUAL DETOX

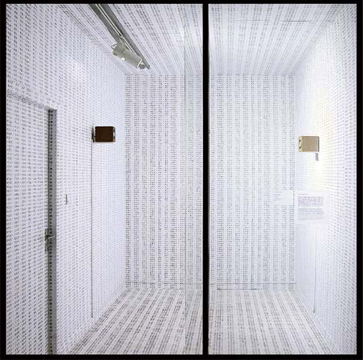

IF SOUND ART has been around in China for 12 years, then we can probably pinpoint its beginning to December 9, 2000 and the Li Zhenhua-curated exhibition “Sound” at China Contemporary Art Gallery (formerly the CAFA Museum) near Longfu Temple in downtown Beijing. Li Zhenhua, who had just returned to China from the UK and, with the memory of his interaction with sound artists there fresh on his mind, come upon three artists as keen on this thing called “sound art” as he: Zhang Hui, Wang Wei, and Shi Qing— three artists who today would certainly not be associated with such a term. Likewise, the exhibited works were far removed from what we now consider sound art. Shi Qing’s Spoken Language Stage and Wang Wei’s 70kg + 3.2m3 were essentially video installations, whereas Zhang Hui’s Lost Voice verged more on actual sound art. In this installation, sound sampled from the milieu of the street outside, intermixed with the sound of someone asking for directions, are emitted from a black wall. Meanwhile, a series of warped cassette tapes hang outside on the street, in what we might regard today as a social intervention.

However you look at it, what the exhibition revealed was, rather than an attempt by a few artists to make sound art, an installation that was conscious of sound. In Switzerland 12 years later, Li Zhenhua recalled that this “sound art exhibition” might have been more aptly termed “an exhibition triggered by sound.” Yet under the circumstances of that time, the exhibition was not without its significance. Artists then had become aware of the need to break the prevalent breed of insipid exhibition, which under the guise of the “conceptual” had become increasingly suspect, removed from both body and site. A solution to this could be found in a focus on hearing, or in using sound as an element. Concurrently Gu Dexin and Wu Ershan had begun to use meat as their own such element, and Qiu Zhijie had begun to stand out for his talents in research and writing, publishing articles on Post-Sense Sensibility and others, in which he accurately illustrated the anxieties and demands of artists by proclaiming the “Post-Exhibition Age.” In the same period, Qiu had mounted a solo exhibition in Japan titled “Sound of Sound,” which consisted of three silent installations. His exploration of sound occurred on a visual and psychological level.

In July 2001, following the series “Sound of Enlightenment,” Qiu Zhijie and Li Zhenhua jointly curated the sequel to “Sound” at Li’s Mustard Seed Garden. They called it “Sound 2.” This time, sound installations occupied the main component of the show. Qiu commented at the time, “We have finally arrived at an inevitable moment: an exhibition of cacophony.” In 2012, Li Zhenhua reflected, “Many works had started to move in the direction of sound art.” The exhibition came on the heels of the exhibition “Retribution,” in which the majority of the Post-Sense Sensibility movement took part. Wang Wei’s Close Contact created a labyrinth of passages to connect two exhibition halls together, and sound was an integral element used to enhance the bodily experience of space. Li Yong’s Happy Drum Beats consisted of a small squirrel in a round cage. As it moved, the soles of its feet sent sand through the cage onto a bass drum positioned below— mimicking musical structure, the piece engendered a sort of biological instrument. Qiu Zhijie describes the exhibition beautifully: “‘Sound 2’ was ahead of its time, a thing of frenzied experimentation that, without an ounce of planning, attempted to lay out all the propositions of sound art within the artistic reality of China.”

MELDING EXPERIMENTAL, NOISE, AND MEDIA ART: CONSTRUCTING AN AVANT-GARDE ART WORLD

NEVERTHELESS, “SOUND 2” proved to be something of a phenomenon in that, from within the framework of contemporary art, it discovered an important link for the development of sound art in China. Namely, in complement to the installations curated by Qiu Zhijie, Li Zhenhua had organized a series of live performances from experimental musicians like Feng Jiangzhou and FM3.

This is highly significant in a number of ways. Firstly, live performance was introduced into the exhibition space. Consequently, certain Chinese experimental musicians began to make a name for themselves in contemporary art circles. It was precisely these people who would consciously take up the cause for sound art in China. Furthermore, Li Zhenhua, who even before these sound artists had come out into the open, had in the role of independent curator begun to stand up for the curation and archiving of sound art.

Just as the art world had begun to wield sound art in its fight against insipid exhibition, the activities of FM3, Feng Jiangzhou and others from the musical world demonstrated how to utilize the ideals and creative methods of sound art towards producing new breeds of music and performance, and even towards resisting and breaking down the barriers between the two.

FM3 is certainly the most interesting experimental music group of the turn of the new century. At its inception in 2000, the group had three members, but due to clashes of principle, it quickly turned into a duo: the devout experimentalists Zhang Jian and Lao Zhao. Their early performances were marked by specific, machine-made frequency generation, laptops, and live vocal loops. The result was strikingly similar to the work of John Cage. They prided themselves as a “silent” band, and on their brash approach to experimentation.

From the perspective of physics, sounds are essentially vibrations. The oscillations of sound waves are a source of nourishment and joy for the intricate mechanism of the ear. Looping pure frequencies is a way of transforming the joy of listening into a meditative process. When FM3 invented their Buddha Machine, they also created commodified sound. The Buddha Machine is a small self-powered plastic box with its own power supply, small speaker, and pre-programmed content (nine mp3 tracks ranging from 2 to 42 seconds in length). The original model was intended as a device used by Buddhists to listen to chants, allowing unlimited replays within the allotted battery life. In an era of increasing digitalization, FM3’s move to go against the mainstream by producing the Buddha Machine garnered praise in both academic and commercial spheres. Their performances became rituals where the Buddha Machine was played live in the dark, reminiscent of Nam June Paik’s “mandala-like” employment of Buddhist imagery and cathode-ray tubes. Anyone who owned a Buddha Machine could take part in these performances; participation in or creation of experimental music performances was instantly imaginable. Yet the applause for the Buddha Machine was also mass appeal, and the device became a limitation for FM3. They began to produce and promote updated models, in terms of allure turning it into something akin to the iPod (or at least iPod Nano, in that it came in a variety of different colors). Their performances also became more and more audience oriented, drifting further and further away from their original claim of a “silent” band.

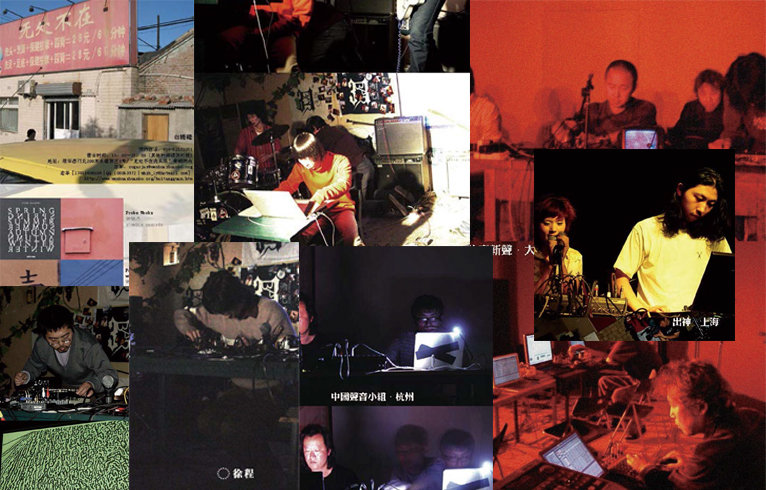

Around that time, in 2003, Dajuin Yao organized the international electronic art festival “Sounding Beijing” at The Loft New Media Art Space, Beijing. Publicity for the event featured certain keywords to illustrate the nature of the event: experimental music, noise art, sound art, and media art (“interactive multimedia, psychedelic sampling, video improvisation, laptop fury, extreme listening, explosive audio, computer folk, information overload, fusion of man and machine, high-tech electronic music, hardcore noise, magical realism, unknown sounds”). This event is widely regarded by those in the noise and experimental music scene as the first major happening for sound art in China. Here was a platform on which Chinese and international music pioneers could come into contact with one another for the first time in China. Particularly notable was the first live performance in China for the Polish composer Zbigniew Karkowski, which influenced many people.

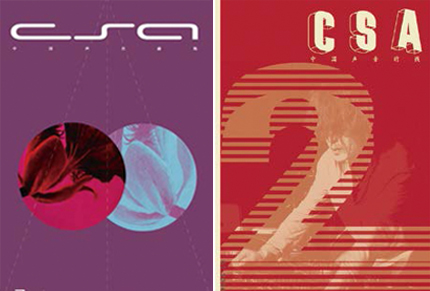

The event also played a direct role in elevating the aforementioned art forms in China to new heights. FM3, CY (Ding Dawen), B6 (Lou Nanli), and Li Jianhong, among others, began to perform in Europe. Hangzhou held 2pi Festival, and published two editions of the magazine CSA. In Guangzhou, the impromptu sound artist collective 21st Floor was established. In Beijing, the poet, sound artist, and co-organizer of “Sounding Beijing” Yan Jun began to lay the foundations of a scene that lay between experimental music and sound art. The Waterland Kwanyin event series began to take off, and in 2005 the experimental-minded Mini MIDI was incorporated into the larger MIDI Festival. The next year saw “Sound From the Far Shore” included in the Dashanzi International Art Festival, and 2007’s “Get it Louder” included a new section titled “Curry Show.” In 2008, the Shanghai eArts Festival opened with a performance called “Streaming Objects,” supported by the local government as a deluxe edition of the “Sounding” arts festival. These people and events, as well as all those we cannot afford to mention here, have experienced many ups and downs, but they have all served to blend experimental music, noise art, sound art, and intermedia art, ultimately helping birth a new avant-garde art world in China. Fast forward to 2011, when Dajuin Yao curated “Sounding Hangzhou” at the School of Inter Media Art at the China Academy of Art, and Li Zhenhua curated a performance by Wu Quan for Goethe-Institut’s “40 years of German Video Art.” We can almost regard this period as a brief revival of a golden era.

MULTIPLE IDENTITIES, AN INFATUATION WITH THE AVANT-GARDE, AND THE BIRTH OF SOUND ARTISTS

IN 2012, EVEN if new events or collectives continue to emerge, there can be no doubt that sound art has already reached its zenith. Looking back again at the flurry of figures and events of the past 12 years, most striking about the underground period have been the contemporary artists, rock musicians, graphic designers, television music composers, computer geeks, and poets… People of all stripes have come and gone on the sound art stage; but those who have stayed on top long enough to meaningfully apply their unique methods and languages to the exploration and practice of sound art are extremely few in number. If we study each artist on a case-by-case basis, we would discover that to this day, these cases have had an incredibly finite lifespan. This forms a striking contrast with Taiwan, where 20 years of sound art have engendered demonstrably rich artist histories, artworks, and happenings. In the areas of noise and experimental music here, many names have disappeared without a trace. Some these people have turned to sound collaboration with video and conceptual artists, while others have become video, photography, and new media artists themselves. In particular, these new new media artists have benefited from a more expansive creative space.

The zenith that sound art enjoyed in China now appears like a pimple, representing, perhaps, the weariness of conceptual artists and rock musicians facing the inevitable end of their adolescence. The phenomena have been many, the legacy limited, and the research incapable of keeping pace. The old have grown up and taken their leave, and the new blindly consider themselves to be the very first true “innovators.” Li Zhenhua believes the rise and of fall of sound art is a direct outcome of an infatuation with the avant-garde of the 1980s. He concludes that it is strongly marked by adolescent impulse. As both curator and a preacher of sorts, Dajuin Yao has come to exercise a far-reaching influence with his archival awareness, organizational work, and his mysterious research collective “Chinese Sound Unit,” which, if it can survive, is faced with the necessary task of combing through the last ten years of variegated practice in China— a task they have only just gotten off the ground. Not only this, but Li Zhenhua and Dajuin Yao have begun to lean towards (new) media art in their curatorial work. Meanwhile, the Qiu Zhijie who once aimed to topple conceptual art through sound is now throwing his energy into the amalgamation of performance, sound, photography, theater, and other art forms in what he dubs “Total Art.”

The limits of sound art, to a great degree, are rooted in the very dilemma of how to understand it. Sound is a source material; fundamentally speaking, it is difficult to discern it from other media. Without concept, performance, or substance (installation, imagery, or other visual supplementation), sound art in the purest sense remains nothing other than, well, pure concept. Theoretically speaking, developments in the Internet and software, as well as those in the transmission and sharing of online media, real-time communication platforms, and mobile devices, have greatly contributed to developments in sound art (and other media art). What’s more, noise and experimental music have incisively improved on the lessons of Japan and Germany, to the point that they may now begin to probe their own unique languages. The revelry has now ended, which presupposes a true turning point for the scene. True, at the very least, in the sense that with people like Li Jianhong, Wang Changcun, Lou Nanli, and Xu Wenkai, who have nurtured their practices over many years now, we may already discern the birth of a new generation of true sound artists.

(This article has received invaluable guidance and support from Li Zhenhua and Ya-Zhu Xu. I would also like to express my warmest gratitude to the following people for their assistance: Chen Wei, Gong Jian, Guo Juan, Jin Shan, Lou Nanli [B6], Shi Qing, Wang Changcun, Wang Gongxin, Wang Wei, Xu Wenkai [aaajiao], and Dajuin Yao.)