DAWANG HUANG SHAKE, TWITCH, CONVULSE: A Dialogue on Sound and Body

| September 21, 2012 | Post In LEAP 16

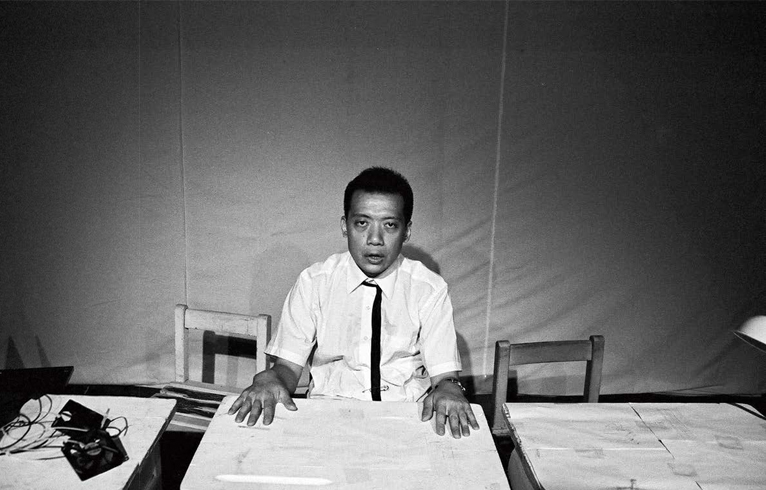

IT WAS WHEN we found ourselves tone-deaf and with two left feet that we fell in love with noise. Since his performance at The WALL in June 2011, “Blackwolf Nagashi” has made converts of music fans of all stripes in Taipei. With the release of his debut album Blackwolf Nagashi in Bedroom in May 2012, the attention has remained equally widespread. Born in 1975, Dawang Yingfan Huang a.k.a. Blackwolf (a.k.a. The Wolf of Dark Campus Folk Songs) had already started to record and listen to a huge and diverse quantity of music in high school. Twenty years later, he is putting out his own releases one after another. After returning to Taiwan from Japan in 2010, these can be boiled down to three categories: free improvisation, electronic noise, and “Blackwolf Nagashi.” The latter enjoys a more universal appeal, evoking laughter as well as serious ref lection among audiences. Sound is the reaction of material movement, and in all types of material, the body occupies a crucial position. For those who have seen or heard Dawang’s performances, it is hard not to be drawn in by his grotesqueries. For one, he resuscitates those sounds and images that we artificially or intentionally ostracize from our daily lives. These “dregs” exist in “unfinished” form. Huang employs his body, or more precisely, his lower body, in his performed and spoken revitalization of these dregs. For this reason, we have invited none other than the corporeal visionary and theater director Wang Mo-Lin to have a conversation with Dawang Huang. (Zhang You-Sheng)

Wang Mo-Lin (Da-Mo): Theater director

Huang Yingfan Dawang (Dawang): Sound artist and singer

Zhang You-Sheng (You-Sheng): Sound artist, curator, head of Kandala Records

DAWANG: Let’s begin with the 1960s! The 1960s had some exemplary singers, like Jim Morrison of The Doors, or the female rock singer Janis Joplin. The rather schizophrenic Morrison was able to, in his lyrics as well as his poetry, expand infinitely in a dark, nihilistic psychedelia, which lead him to be seen as a kind of “anti-rock” figure. This was completely antithetical to the hippie spirit of peace and love of the time.

DA-MO: Woodstock was the perfect embodiment of the 1960s rock and roll spirit— the subculture of the hallucinogen. Compared to American rock and roll, which is derivative of Elvis Presley, European rock is completely different, much heavier. They have already dug deep into the darkness of life. It’s not a subculture anymore.

DAWANG: European rock really emphasizes the individual experience. The dark side is the bottom line of a person’s spiritual world.

DA-MO: Dawang’s live performances also possess powerful storytelling, which shapes another spiritual world. His perspective on society informs many of his stories. His performances are all about playing around, and it is when his performances have been thoroughly played out that his social attitudes emerge. Music shouldn’t be moral display. One shouldn’t be so tightly bound— that’s not rock!

DAWANG: A lot of people appreciate rock for the lyrics. Rarely do you see rock as an element of mythology, rock that through musical structure clairvoyantly penetrates the contemporary materialist world, rock that acts to experiment with physical sensation. I’ve no desire to establish that kind of traditional mythology; my stories are imagined out of thin air, on the spot. These might appear to be nothing more than a pile of meaningless jabber supported by a flawed logic. But my body morphs according to the role it assumes, borrowing the voices of women, old people, and infants to tell its stories.

DA-MO: What I meant was a spiritual world born out of physical sensation, and stories or mythological feeling expressed therein. This often happens in simple movement, in the body twitching, shaking, or what have you.

DAWANG: That’s how I am usually! Shaking, twitching, or having convulsions. When I am up onstage, even if I am covering a rock song, I’m singing with an anti-rock spirit. People are exasperated by this kind of subversion, but for my audience, it becomes interesting. I become a real bastard in their eyes.

YOU-SHENG: Take the bands Labor Exchange and Chthonic, for example. Their music and lyrics articulate a social standpoint. The reality they embody seems to have been filtered, and molded into beautiful scenery— something we absolutely must aspire towards. Dawang, on the other hand, sees the suffering in reality, whether in the future or in fairy tale. He has no mission to make a beautiful future— he knows the future is already beset with misfortune.

DA-MO: This is, simply put, anarchy. Your sense of being is rooted in your present reality. Whether I choose to accept you or negate you has no bearing on your sense of being. Without a sense of being, the schizophrenia Dawang refers to cannot take place. And one can only subvert while in a state of schizophrenia— I refuse to acknowledge having anything to do with you, and even less, that I am the same as you.

DAWANG: In other words, that the state I am in when onstage is, from everyone else’s perspective, the focus.

DA-MO: The microphone is very important to you. I feel that the sounds that come out of your microphone are pretty abnormal and psychotic. The sounds come from your throat, so they seem congested. Your speech is also intermittent. When you search for the space between speaking and words, it becomes crammed with sound. It’s not like how we normally talk—you use the throat directly to produce sound. It feels like something is blocked, like someone stepping on the throat of a chicken. The sound is in a state of convulsion. People begin to worry what you will say next.

YOU-SHENG: I think his voice expresses a kind of incomplete idea, one that will never be complete. Any band must present a comprehensive idea. If you want to advocate this or that ideal, it must first be imagined in the form of an image. The microphone receives the resultant sound from the brain, which achieves clarity through lyrics, and is then transmitted vocally. However, the sound from Dawang comes straight from the body. Everything is in complete disarray. From the first song through the tenth, you never know if completion will be achieved. He might even get riled up in the middle of a song and move in a completely different direction.

DA-MO: The microphone is an extremely sensitive thing. It’s so transparent it even picks up your breathing. The tempo of Hitler’s speeches was so fast that it wouldn’t be long before they reached a high. This kind of high can only be heard through the microphone— a kind of performativity of sound. When onstage, Dawang is not just speaking, but yelling. The microphone amplifies his convulsions. I think his voice is an intense embodiment of the voice of the Other.

YOU-SHENG: There are some bands that resist by positioning themselves opposite the system. But Dawang actually seems to imitate the system. But his failure is a satire of himself, and of the system. In order to speak, he embodies every possible kind of “you.”

DA-MO: This “you” is the voice of the Other, physically hidden inside of Dawang. The Other is crammed inside his throat, hence the clogged feeling. It doesn’t come from the head— you could say Dawang’s mind is resistant to control. His voice and his breathing are in the midst of an argument, and together they exit the microphone in an exaggerated, neurotic kind of performance.

YOU-SHENG: So we could consider Dawang’s body to be separate from his soul.

DA-MO: Bands use various methods to control their performance so that it is just right. Dawang’s performances, however, carry him into stuporous territory. To invoke psychoanalysis: he takes a shit. Onstage he purges the feces from within, distances it from his body. Each of us has the system hidden inside. Dawang often blurts obscenities when onstage— “fuck your mother,” and so on.

DAWANG: I swear a lot in the song “Happiness RV,” probably because I’m happy myself!

DA-MO: Even when you don’t say “fuck your mother,” I still feel like you’re cursing. This is not a result of my expectations, but instead has to do with your body. Every time you perform, you rid yourself of all that excrement inside. Your performance is a performance of the lower body.

DAWANG: One of my songs says upfront: “It’s been a long time since I took a shit.”

DA-MO: So we should talk about rock and roll in terms of the body, rather than of lyrics or political stance. Dawang flushes out the excrement of his system, separates it from the body. You could say his obscene language is a kind of self-cleansing.

YOU-SHENG: There are many bands that only talk in highly polished pleasantries. What Dawang stands for is bullshit as a form of speech. His words shoot right out of the throat and are a type of exegesis— even if what he actually says is bullshit.

DA-MO: His voice is not processed by the mind. It seems direct, as if it had taken a shortcut. Our throat and anus are actually interconnected; sometimes when you cough it makes you fart. The system never discusses the anus or the throat. When Dawang speaks, he is just farting— this is the culmination of a theory of his body. When he begins to speak, the rectal veins open up, and the asshole gets to work farting. This improves the digestive system. Otherwise, he’d get indigestion whenever he takes a shit.

YOU-SHENG: So Dawang farts onstage. It’s a political struggle with the system for the right of speech.

DA-MO: Every one of us has the right to speak in the public sphere. But this right has become standardized, turned into a construct. If we are talking about free speech on this level, then Dawang can’t “speak,” because other people aren’t keen on listening to the Other. When Dawang speaks, the sound is born from this convulsive state. It’s intensely private in nature. People see it as a tangle of secrets that they will never be able to comprehend.

YOU-SHENG: But a question: where do Dawang’s farts come from? Normally you have to eat something before it turns into a fart. Dawang fre- quently notices things that other people consider unimportant. Whereas an average person takes theory as a source of nourishment, Dawang’s nourishment is the trivial, the marginal, the dregs of society. He doesn’t consider any of this a source of rhetoric. He is just involuntarily attracted to it. He “eats” the stuff everyday, and “shits” it, too. A normal artist wouldn’t be able to handle the same information.

DA-MO: In terms of the contemporary, what his body represents is the reconstruction of subjective expression, action of conscious being, and the location of its own modernity. This is the only way dialogue with and connection to capitalist modernity can be forged. All the clamor on the outside, the anti-nuclear protests— the rules to this game aren’t unique to Taiwan. The main issue is whether or not capitalism wants to play this game. To be anti-modern, to call for a return to tradition, to return to the rural lifestyle: this is but a dream of the Rusticated Youth. In Taiwan, if nobody rebels against modernity, then we can’t produce modernity. This is why I am interested in Dawang’s performances. His body onstage is a haphazard existence.

YOU-SHENG: When Dawang rebels against something, he does not strike at it. He is like a soft, muddy beach: squishy, and if you hit it nothing happens. He is dangerous in that he is “soft,” unpredictable, unmanageable.

DA-MO: In other words, when he is absentminded, when consciousness is not present. He basically enters a trance, incapable of speech— a state of turmoil. So where does his will for movement come from? I really admire Dawang’s will for movement. Once, in a cemetery, he began improvising as a “snail.” He lowered his waist to the ground and crawled forward. He did this for so long that it began to be disturbing. The improvisation was brimming with this feeling of crisis; it completely toppled the way our brains are programmed to deal with time.

DAWANG: There was one time during middle school when the teacher handed our exams back. I got a bad grade and just screamed out loud, “fucking motherfucker!” The teacher sent me outside, but my anger only became more difficult to control, and keeping my mouth shut even harder.

DA-MO: I think that when people find themselves convulsing or in a stupor again and again, they enter an a priori mental state. The more they don’t want, the more they want. It brings about a state where your mind is inhibited. You don’t seem to need to rely on words to exist, like us.

DAWANG: I call this phenomenon a kind of flashback, which also encompasses the informationality of words.

YOU-SHENG: A dialogue with you, then, cannot resort to language. I wanted to ask you about your past experiences before, but couldn’t imagine the possibility of direct dialogue. For example, when you improvise there is such an overwhelming feeling of crisis— like just like a moment ago, when suddenly there was this strange sound.

DA-MO: Lastly, let’s talk about your stage. Although it seems quite shoddy, this lo-fi approach is also an act of resistance against capitalism. Rock music today neglects the body, and can easily devolve into but a specimen of the capitalist cultural industry. Only with the body can you drive the creation of history.

DAWANG: That’s right! My setup includes only a chair and a microphone. The rest is just air.