YUN-FEI JI: ALLEGORY IN INK WASH

| November 9, 2012 | Post In LEAP 16

In the ink wash paintings of the American immigrant Yun-Fei Ji, the equivalent of nostalgia appears as the reflection and examination that follows the rejection of modernity, not as an aesthetic decision based on questions of cultural identity. His works bear the marks of his generation, as well as a critique of reality. Together, the two compose the artist’s narrative, which falls just short of fable.

ON MARCH 16, 1983, an article with the title “The Relationship between Marxism and Humanitarianism” appeared in the People’s Daily. Zhou Yang, the renowned writer who penned the article, intended to mark the hundred-year anniversary of the death of Karl Marx. The article’s discussion of “humanitarianism and issues of alienation” was related to the emphasis on thought liberation post-Cultural Revolution, as well as the move away from extreme leftist positions in political spheres. Zhou’s arguments were based on the young Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. What Zhou Yang could not have expected were the various reactions to his article within the Party, which would directly trigger the national Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign.

The campaign was short-lived, but for the painter Yun-Fei Ji, the brief cold snap in China’s political spring was sufficient to tip the scales of a life-changing decision. Ji had just graduated from the oil painting department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and he knew about the assorted brands of political oppression his instructors had suffered during the Cultural Revolution. He decided to go abroad to continue exploring his artistic horizons. Even today, Ji is unclear as to how the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign began. He chose to leave China at the time solely in order to avoid the potential sudden return of leftist political control and the unhappy fate suffered by the previous generation of artists.

Yun-Fei Ji arrived in the United States in 1986 and eventually settled in Brooklyn, where he encountered a completely new cultural landscape. But already at that time, life in the so-called Western world was much closer to life in China than he had expected, and all his imaginations from before suddenly seemed trite in the face of the everyday. In terms of both arts and politics, it was a process of desacralization. In this context, Ji was obliged to continually reconsider and adjust his relationship with the outside world. He switched to the medium of ink wash painting in 1990— his youthful hopes of pursuing the avant-garde had morphed into a more confined and conscious artistic sensibility. Choosing not to focus on the exoticized Eastern characteristics of his new medium, Ji instead occupied himself with the operation of the traditional ink wash vocabulary. His figurative portrayals of people and scenes cast familiar existence in new light. In other words, the issue of cultural identity as raised by the process of modernization is for Yun-Fei Ji notan end but a beginning, proffering material for new lines of inquiry and reflection.

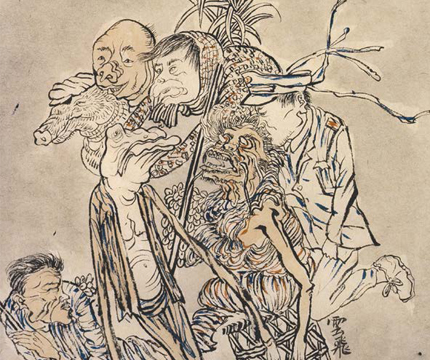

Yun-Fei Ji’s ink wash paintings often seem to contain completely contrasting ideas. Regarding his own work, he once wrote, “I like the relationships of contrast and contradiction between various elements. When you look closely at something that may seem peaceful and static at first glance, you may discover anxiety concealed within.” “Peaceful and static at first glance” are characteristics attributable to the formal standards of language, style, and composition in traditional ink wash painting. These brushwork aesthetics evoke the approach of an old-fashioned Chinese scholar. If returning to the ink wash medium implies a kind of nostalgia, then the narrative aspects of Ji’s paintings form an intellectual attitude that reveals how his nostalgia has become an unsolvable riddle. The “anxiety concealed within” is closely linked to Ji’s political experience prior to leaving China. Ji has portrayed China’s various political campaigns, such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, in paintings including Public Grain and The Seven Scholars. In his paintings, the autocracy takes the form of clowns or mythical beasts, in expression of the inhuman and absurd characteristics of political campaigns.

Yun-Fei Ji has also transferred his critique and wariness of political power to his interest in contemporary American political reality in works such as On the High Branches and Mistaking Each Other for Ghosts. On the High Branches addresses the technique of unified media propaganda employed by the United States government in the run-up to the second Iraq War. The painting portrays a loudspeaker distressing a group of birds, suggesting the duping of the American people by government power. Mistaking Each Other for Ghosts draws on a fable from Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, in which two men each suspect that the other is a ghost. The painting evokes the societal paranoia caused by the FBI’s post-9/11phone-tapping operations, justified in the name of counterterrorism. Ji’s allegorical exposure of abuses of political power originates in his strong understanding of the logic between authoritarianism and mass suffering. But his ruminations do not end there.

Yun-Fei Ji’s most well-known series is based on the Three Gorges Dam, which draws a connection between the artist’s personal nostalgia and the homelands lost by displaced people in the process of modernization. He traveled deep into the Chinese hinterland, conducting ample research and sketch work. Much like the Socialist Realists of days past, he immersed himself in real life. However, this series of paintings does not exalt hydraulic engineering as a symbol of modernization; rather, it depicts the collective loss caused by such projects. The building of large dams has resulted in the relocation of thousands of peasants and the destruction of their houses, the contents of which often end up in desolate waste heaps. They look like piles of commercial goods, but by superimposing them amid the traditional motifs of streams, stones, and forests, Ji creates a grotesque, unsettling effect. In the scrolls The Three Gorges Dam Migration and Last Days of Village Wen, Ji portrays the losses (sacrifices) of China’s century-long journey of modernization. Included in these portrayals are “the people who are least able to make sacrifices and of whom the greatest sacrifices are demanded.” He shows how modernity has destroyed people’s relationships with their homes and their reverence for the natural world. Clearly, Ji’s nostalgia is a kind of historical empathy borne of contemporary social and psychological trauma.

Yun-Fei Ji has presently taken up temporary residence in Beijing for personal reasons. China’s reform era has lasted more than three decades, and people rarely speak of the political campaign that drove Ji to go abroad. However, the phenomenon of alienation raised in Zhou Yang’s 1983 article remains relevant to contemporary Chinese reality: “Because democracy and the legal system remain incomplete, public servants at times abuse the power entrusted to them by the people, turning it around to exercise it as masters. This is political alienation, or, in other words, the alienation of power.” Even though Zhou’s article seems buried in the ashes of time, unspoken does not mean forgotten. It is a quirk of history that at certain junctures of the present we are always confronted with the ghosts of the past. Perhaps Ji’s paintings are such a juncture. They reveal social and psychological traumas that authority has hidden away; they frankly address the fractured, irreconcilable aspects of our lives.

In the words of Foucault, “The work of an intellectual is not to mold the political will of others; it is, through the analyses that he does in his own field, to re-examine evidence and assumptions, to shake up habitual ways of working and thinking, to dissipate conventional familiarities, to re-evaluate rules and institutions and to participate in the formation of a political will (where he has his role as citizen to play).” We cannot see indications of where the future will take us in the works of Yun-Fei Ji, but we can discover within his paintings the power to change the present. If Ji’s paintings can be called allegories, then the boundary between allegory and prophecy is to be found in action.