THE ART MUSEUM: ON KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTION IN ART HISTORY AND INSTITUTIONAL ASSURANCE

| March 11, 2013 | Post In LEAP 18

IN THE INTERNATIONAL context, the art museum is usually an academic institution of collection, centered on twentieth-century art historical research and open to the public. If the art museum did not establish this basic objective in its work, it would not be able to provide the scholars and students of the world with such a fundamental resource, inspiring them to carry out original research. Nor would it be able to continuously attract outstanding scholars from home and abroad to come to conduct research and exchange with their international peers. Without this premise for scholarship and engagement, so-called research would just be a regurgitation of pre-established narratives and positions. Many of the difficulties faced by the study in China of twentieth-century art history can largely be attributed to a lagging in the very construction of the museum.

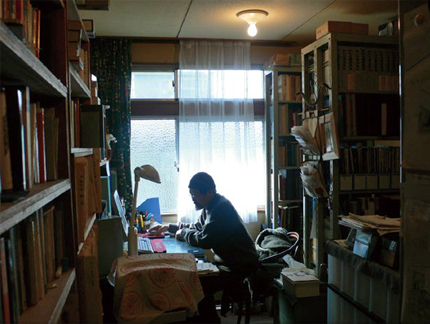

In Japan, the name for a curator of an art museum can be literally translated as a “student of art.” Curators’ daily work is comprised of acquiring and researching collections and planning and organizing exhibitions around specific subjects. From 1980 to the present day, the system of fine art museums in Japan has found its stride. Rooted in a foundation of intimate exchange with kindred institutions and academic projects in Europe and the United States, special topic exhibitions organized by Japanese curators have made substantial progress in terms of both their scope and depth. This progress to a large degree exemplifies the increasing self-awareness of Japanese art museums, in that they are departing from the mode of the early days when exhibitions bore the burden of combining and recombining sprawling subject matter, and are now growing into a more professional role, guided by the notion of a curator as a scholar who possesses independent research abilities and who is directly responsible for a museum collection. This is the key to an art museum’s ability to sustain the development of academic characteristics unique to its establishment. The factors that go into investigating whether an art museum reaches a certain academic standard are often simple; it is often just a matter of the conditions of the art library. I once interned at Japan’s Tokushima Prefectural Modern Art Museum. Even in Tokushima, an economically underdeveloped district, the comprehensiveness of the fine arts library collection was still breathtaking. In addition to original documents from the Meiji, Taisho, and early years of the Showa, a large number of domestic and foreign exhibition catalogues, auction catalogues, and even microfilm archives from museums all around the world were all readily available. The amassing of such a comprehensive database was in reality the result of the steady accumulation of the work and research of curators each focused on their respective fields. Almost every person’s desk was equipped with its own sale catalog for book merchants and antique bookstores, always at the ready for an order placement. The most lasting impression in my memory is still the distance between the curators’ offices and the library. The curators needed to only take one step, and they were there. Their daily research was conducted at the physical intersection of the collection and the library, so drastically different from what we see in China.

In terms of their institutional design, public art museums on the Mainland face the problem of the bottlenecking of workflow, and this must be resolved. Many of our art museums have set up separate research departments (academic departments) and collections departments, effectively separating academic research and collections management. On the surface this would appear to be more professional, but in reality it results in mutually erected obstacles for both research and collection. Because their work includes coordinating across sections, members of the research staff must get through the procedures of the collections department in order to get to the collections. In actuality, they receive the same treatment as that of a visiting researcher. Essentially cut off from the collections department, the research department ultimately ends up serving as nothing but an exhibitions coordinator, operating according to the will of the executive curator. This is an absurd systemic flaw, and deeply hinders the progress of a museum’s original research contributions.

Though the earliest public art museum in Mainland China appeared in the 1930s, the construction of a museum of fine arts in the strictest sense of the term is actually only a thing of the past few decades. Prior to this, functioning as a vector for ideological propaganda, the art museum had no way to initiate independent research. From the mid-1990s, following an increase in occasions for international exchange, a number of high-level international exhibitions came to China, and more opportunities arose to arrange exhibitions of domestic collections abroad. These exchange efforts got those in power thinking more about the professional function of the art museum, while at the same time, rapid flux in the international environment endowed the construction of an art museum in a post-Mao era with a new allure. How could the art museum most effectively gain social influence? How, in the shortest amount of time, could it attract the largest amount of media attention and public awareness, transforming into a modern art institution with a cutting-edge image? As Chinese contemporary art heated up around the world, a contradictory phenomenon emerged: on the one hand, the original collections frameworks and exhibition histories of national and local art galleries were built upon the structure of the power and knowledge base of the Chinese Artists’ Association at both central and local levels, with little systematized understanding or expertise regarding areas of art history prior to the 1980s. On the other hand, accompanying enthusiasm over a new alignment with international standards, a strong push by the art market brought about the hurried debut of the biennial and triennial system. It is without any doubt that the art museum ought to respond actively to this visual culture as it unfolds, and this new development indeed helps to bring the visage of a traditional art museum to fruition. So the functional conversion of the museum has been extremely effective. But the problem with this is that the art museum in Mainland China, under circumstances for which it is not yet fully organizationally prepared, in which its fundamental research has not yet begun, and in which its research teams are lacking— is hastily pushed into a worldwide “post-museum” movement. The consequences of this battle over resources are grim, and mean that museums’ human, intellectual and financial resources are for a long time devoted to the steep undertaking of organizing a biennial or triennial: the so-called “museum-lift” system. Meanwhile, the curator of the bi- or triennial is often someone brought in from the outside. Can a research team with this degree of liquidity and personnel with this rate of turnover be forces for the cultivation of a museum’s academic strengths? The answer is right in front of us.

The art museum represents a kind of universal value, reflecting the profound concern of all nations for modern civilization. It is a serious academic undertaking. Europe, the United States, and Japan have all enjoyed steady, century-long building processes, and China is the last one to enter the scene— suffering, on top of this, from long-running systematic ills stemming from the intervention of power into the profession. The building of an art museum cannot be done overnight. Yet it is an urgent priority, one that needs corresponding institutional assurance. It requires a guarantee that professionals and teams in the field can be granted the space and support for steady growth. At the stage in which we currently find ourselves, we must think about sending researchers abroad for advanced studies, so that they can form more global perspectives and networks and bring their museums’ respective collections and research divisions into academic dialogue with international counterparts, eventually launching high-quality, research-centric exhibitions.

In 2007, Dr. Kure Motoyuki of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of the University of Tokyo and I jointly curated “Floating Avant-Garde: The Chinese Independent Art Society (Zhonghua Duli Meishu Xiehui) and Modern Art in Guangzhou, Shanghai and Tokyo in the 1930s.” The success of this research exhibition was a testament to the ample space provided to art museums by Mainland China’s present conditions. First, Wang Huangsheng, then director of the Guangdong Museum of Art, fully endorsed the academic value of this plan; as a key project marking the tenth anniversary of the museum’s establishment, the exhibition was put together with extremely efficient interdepartmental coordination.

Secondly, I myself was provided with sufficient conditions to conduct independent research. Research for the exhibition spanned three years, and the scope of investigation included art galleries, museums, libraries, and collectors in Paris, Tokyo and several cities in China. Lastly, Kure Motoyuki and I engaged in collaborative research, each playing to his own strengths and inviting international scholars from relevant fields to participate in the discussion. The exhibition enjoyed the material and technical support of dozens of organizations and individuals from home and abroad.

Most of the trials confronted by early twentieth-century Chinese art history are related to the phenomenon of cross-contextual exchange: of how to tell the tale of all of those topics— coated as they are in the residual dust of history and enshrouded by political culture— in the language of the art historical profession, and how to communicate them to the public through the dynamic format that is the art exhibition. The Chinese art museum is bound, by duty, to play this role, and in playing it steps into a professional area that is brimming with potential and international in scope. As a professional institution, the art museum must undertake professional research to shed light on the historical and cultural connotations of artworks, expanding the volume and depth of historical awareness. The production of art historical knowledge here needs to stand up to serious academic standards; only when the art museum is able to achieve this will it enjoy a reputation of professionalism and dignity.