BENEATH LIFE

| March 17, 2013 | Post In LEAP 18

THE TITLE OF Zhou Yilun’s latest exhibition at Platform China, “As There Is Paradise In Heaven,” immediately brings to mind the old proverb, “the heavens above are matched on earth by Suzhou and Hangzhou.” At the entrance to the exhibition hall, a faded painting scroll featuring the beautiful scenery of the West Lake is displayed on the ground, covered with transparent plastic sheeting, eerily greeting visitors. A majestic stupa stands in the background, partially hidden behind light blue smoke in the mountains, while a dozen-plus new-born babies (or angels) float about in the frame. This clip art-style imagery mostly comes out of middle school art textbooks. Zhou expresses unabashed love for his hometown of Hangzhou, but also warns that the quest for heaven, in both the physical and ethereal sense, must not be slowed by complacency and materialistic comforts.

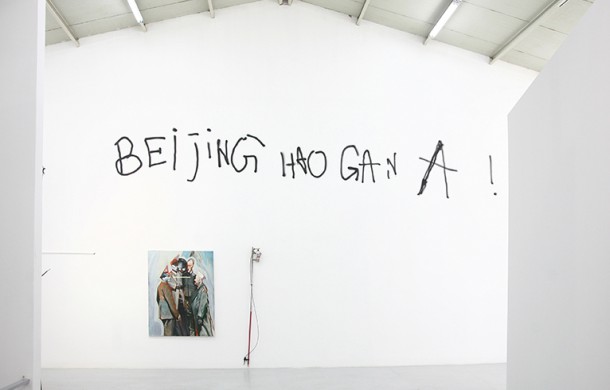

Hangzhou is a reasonable distance from the artistic hubs of Beijing and Shanghai, which allows Zhou Yilun some freedom for alternative personal interests outside of art. He has taken interest in graffiti, rock climbing, bicycling, and long boarding, making for a much more exciting life than that of a cooped up artist. As a young man bursting with energy, Zhou is not satisfied with the superficial freedom associated with exploring new subject matters; instead he pushes the boundaries of art and life itself, attempting to blend the two together. Though a graduate of the Department of Oil Painting at the China Academy of Art, Zhou chooses to speak as an amateur or outsider. For him, art is an instinct, a life habit. Like graffiti, art is created by the here and now, speaks directly to the here and now. That aspect of Zhou’s art has been apparent since 2006. In the exhibition “Fighting Out,” dialog boxes of spray paint betrayed the inner thoughts of the human and animal characters in the frame— no slogans or proclamations, but rather, mutterings under one’s breath. In “Enjoy It?” towards the end of 2008, Zhou mocked the then-popular trend of going big in exhibitions by purposely creating a series of huge paintings, forcing viewers to look at awkward sexual depictions in massive scale. 2009’s “You Came Too Late!” went even further: made of photography and miniature models to ballsy collages and discarded cardboard boxes tumbling down flights of stairs, a panorama of absurd society.

Compared to his previous shows, “As There Is Paradise In Heaven” is of periodic significance. Zhou Yilun continually challenges his earlier works, as if art for him were a process of metabolism. In a sense, this exhibition incorporates all his previous experiments and experiences. The gallery provided him with an empty and autonomous space, allowing him to oversee every step of the installation, from selection to placement. Zhou is well aware of the effect that spatial arrangement has on the interpretation of an artwork— a bright and clean space gives even garbage a chance to be examined. He tries to arrange the space vis-à-vis the rhetoric of “bad painting”: paintings of different sizes are piled together, while large frames are cramped into tiny VIP spaces; recycled bed boards are rearranged into a temporary refuge and serve the dual purpose of a painting surface, allowing attendees of the opening reception temporary respite; modified model toys scattered in the corners, writings on the paintings and behind the canvases, partially covered by crooked painting frames, all vie for the viewer’s attention.

The imagery and words employed in Zhou Yilun’s paintings are by no means unique, but for him, the naming of the pieces and the way they are written on the canvas are akin to the traditional Chinese painter signing his paintings with a poem. The wordings are artistic creations in and of themselves; more than a simple description of the graphic elements on the canvas, they are the endings to melodic poems. The names are humorous and crafty, occasionally a plain recount of the subject of the painting, but occasionally completely unrelated. Zhou readily admits that he often names the paintings for the sake of exhibition or publication. The names themselves are forever a temporary moniker. On another given day he may very well have a new interpretation for the work and come up with a new label as a result of his newfound perspective.

Atypical media and materials are one of Zhou Yilun’s signatures. Discarded materials, second-hand goods, old photographs, magazines, newspapers, and recycled painting frames have all played important roles in Zhou’s art. Ever since childhood, he would refuse to throw away those things that had already served their purpose, and over the years, Zhou the pack rat had amassed a sizeable collection of such old things. Hangzhou, as China’s emerging center of ecommerce— thanks to the dominance of Taobao— is a haven for those looking for materials new and used, raw or fabricated. Outside the artist’s studio, situated at the north end of the city, is a veritable gold mine of materials. He actively collects these items and tries to “feel” the materials: metal and wood with peeling paint or plastics adorned with scratches and stains each present a unique texture, and photo frames that used to hold family portraits or awards still carry with them that sense of love or pride. These older objects stand the test of time perhaps even better than a painting. Zhou is captivated by the marks made by old father time on these old objects, as well as the sense of history felt when handling them. These senses cannot be reproduced or fabricated; they are unique, and form the foundation for his creations. He chooses an object of interest, builds upon its basic form or color, and creates a new work based on that unique foundation.

Zhou Yilun loves to experiment with different materials. He is a

tyrant in their world, randomly amassing, moving, and modifying different objects in order to form his unique artistic signature. Modifying tools, building models, attempting different media, creating collages of posters, magazines, and other commercial imagery and making alterations on that basis are some of the artist’s favorite methods. The Internet has made finding pictures that much simpler. Zhou takes advantage of the over-abundance of commercial imagery and creates an incredible number of pieces. He responds to the cry for political correctness with experiments in image amalgamation, posing a challenge to the blind worship of art’s ability to change the world. The audience may be shocked by the total lack of inhibitions and boundaries in Zhou’s art, but it is truly a spiritual realm in which he roams free.

The output of Zhou Yilun’s rogue attitude towards material and art-making may be easily dismissed as “bad painting,” but “bad” is not all-encompassing. When punk’s individualized performance arrives at cliché, badness becomes nothing more than an empty and powerless gesture. Zhou has received a formal education and possesses excellent control; the badness seen in his work is the result of methodological training and discipline. In his paintings both his deep understanding of Western art history as well as his roots in traditional Chinese painting can be detected. Contrary to most “bad artists,” Zhou has long maintained a suspicion towards earnestness in art. He believes that, as compared to “artists” actively making art as a profession, those who work in other fields but create art as a byproduct are much more respectable. To him, art is but a small part of life; it is beneath life. Rather than asking “what can art be, what can art do?” it is much more practical to consider such questions as “can paintings be a pleasure to look at?” (Translated by Frank Qian)