GO: THE FIRST OCAT YOUTH EXHIBITION

| April 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 2

Things at Shenzhen’s OCT Contemporary Art Terminal (OCAT) are gradually heating up. On January 28, the center’s fifth anniversary celebration, it launched the “Youth OCAT Programs” initiative featuring projects such as the present show “Go,” as well as research initiatives focused on international art institutions and connections between film and contemporary art. Director Huang Zhuan revealed to much excitement at the conference that in the next year OCAT would gradually move to devote one half of its operating budget to programming involving young artists. That OCAT has maintained a stable, contemporary and independent outlook for five years is a credit to Huang’s persistent intellectual-historical approach to contemporary Chinese art; most of OCAT’s success derives from its consistently well-curated, research-driven shows of nationally and internationally successful artists. The newly prominent “Youth Programs” represent a bold and risky change of direction for OCAT.

As OCAT’s first step in this direction, “Go” already has its fair share of problems, and curators Wang Jing and Man Yu have no reservations in passing these problems on to visitors. The show’s cryptic theme does not help much either. The exhibition catalogue presents the entire thought process that went into the exhibition—the curators at first had little idea of what kind of show they wished to put on and hit upon the phrase “going it alone” (qu gu dao) as a starting point for discussion. The curators and artists began a heated discussion, which takes up 97 pages in the show’s catalogue, before finally arriving at the present theme. The five dictionary definitions for the character qu, which most commonly means “go,” are trotted out in a seemingly contrived attempt to explain the artwork with the concepts of “past,” “remove,” “lost, ”“distance” and “where to?” But no convincing or necessary relationship emerges among these concepts. The definitions and the artwork are isolated from each other; were we to change the theme to “come” or “do” it would not really make a difference.

That there are problems does not mean that the artwork is unsuccessful; to the contrary, each of the six groups of work has its own independent character, expressed vividly in medium and concept. Shen Ruiyun’s piece is a very credible presence in the exhibition space, and after viewing the other works one quite naturally follows the passageway to her “room.” Since Guangzhou developers plan to demolish her childhood home, she has moved the room’s floor, brick by brick, to the white exhibition space, painting along the bricks’ blotched traces in a tactic she often employs. The piece reflects multiple contradictions between present reality and the past, individual and society. Addressing the societal transition from old to new along with issues of demolition, the artist uses a poetic mode of expression, making memory and imagination cross time and space to reappear in a present setting.

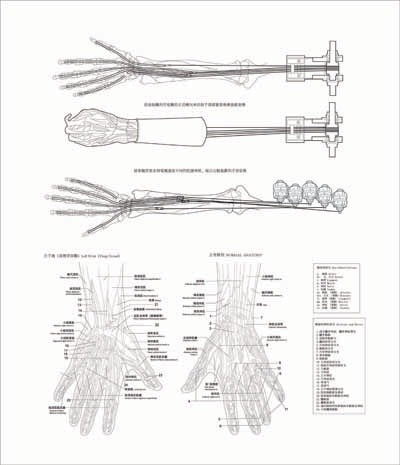

Lu Yang is the youngest of the participating artists and more of a Dr. Frankenstein than an artist. Her plans, including schemes for remaking the reproductive organs of animals, how to kill one part of the body, and a tendon amusement park in which she has cut the hands off of corpses and made them into recreational equipment, demonstrate a taste for the twisted along with a violent imagination. Not only are her experiment proposals complete, the artist, clearly the kind of heretic one rarely finds in the academy, has even announced her search for a scientific team to collaborate with in the exhibition booklet. Doris Wai-yin Wong is representative of young Hong Kong artists, and the video work she has chosen for the show, The Making of Observation Society records her experiences with three collaborators to establish the independent art space Observation Society in Guangzhou. The line between her work and real life is extremely blurry and she distrusts all artwork that claims this distinction;;for her,creating art is dismantling our hardened impressions of reality.

OCAT’s newfound emphasis on “youth” is only very vaguely defined. Each country’s definition of youth is different, and perhaps it is most reasonable to understand “youth” as the spirit of opposition to convention and authority. As for the meaning of “go,” it lies in a foreshadowing of the interests and directions of the young generation of curators and artists, the aspect of this exhibition that is most worth looking forward to. Wu Jianru