Performance / ART

| July 15, 2013 | Post In LEAP 21

Performance art, as a formal concept, has been in China for about three decades now. Over these past 30 years, people have been using the term “behavioral art” (Chinese: xingwei yishu) to describe the concept. In fact, around the time of the ’85 New Wave, performance art began entering mainstream consciousness along with Chinese Modernism. As is the case with Modernism, the art histories and cultural backgrounds that give shape to performance art present us with a hybrid, disruptive appearance of geography and spacetime.

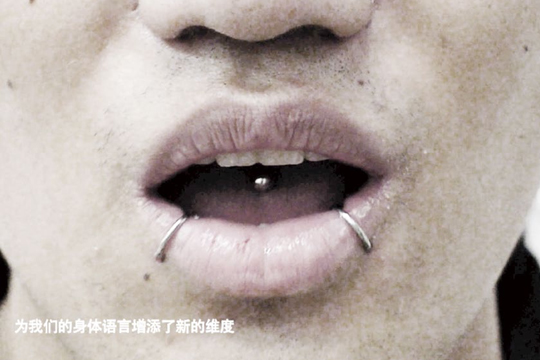

Chinese Modernism takes its roots from the Western conceptual art tradition prevalent since the 1960s, and is nourished by an amalgamation of Western modern art history. Its development, along with other revolutions in Chinese culture, was to varying degrees burned into the very fiber of Chinese contemporary art. The term “performance art,” in particular, has been used in broad strokes in China. Its application has not been consciously distinguished from body art, the performing arts, artistic happenings, or live art. Typically when the human body or the artist’s own body appears in an artwork, or when a particular piece takes the shape of an event, it is broadly classified as performance art. The rough but interesting transplantation of these different forms of art into our creative atmosphere is paired with the action of creating something out of nothing, but also at times involves deep introspection. That these different styles of art are not viewed distinctly lends a richness and complexity that fosters a tremendous raw power, the impact of which on art historical narrative as well as on our ambiguously structured culture and society is intricate and difficult to describe with any sense of completeness.

Therefore, since the very beginning, the very history of the medium as used to describe performance art entails a challenging undertaking that is far from completion. In addition to transplantation, reorientation, and self-wavering, this descriptive history—a history of aesthetics—has undergone its own self-historicization and standardization. Relatively speaking, this history’s focus on making definitions is much greater than its attention to actual praxis. The historian’s language is either given a socially and culturally critical overtone or is impotent or ignorant to any artistic creation that ventures outside cultural conflicts and established ideology. The critic Huang Zhuan once wrote about certain trends in Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s:

“These trends possess a certain level of cultural introspection and a certain critical strength, but either from its critical nature or the visual methodology that it assumes, it hasn’t shaken its old school Modernist roots, which is manifested in various forms of nihilism and cynicism. Clearly, for the Chinese avant-garde to assume the more liberated role of the vanguard and the critic, it must first undergo an inner transformation in its visual methodology and inherent political leaning. In other words, we must move from Modernism to Contemporaryism.”

Huang’s viewpoints may not be directed at performance art and the aesthetic developments that arose from its introduction, but they are still highly relevant. In the language used to describe performance art, “old school Modernism” is manifested as an endorsement for the aesthetics of Modernist art, an irrational respect for the meaning hidden in visual elements, and the deification of certain well-known artists. It lacks understanding of the actual work that goes into the creation of an artwork or the drive for equality.

In 1994, Beijing’s East Village artists Ma Liuming, Zhu Ming, and Zhang Huan, living in poverty and at the fringe of society, had experimented with their bodies in such a way that pushed performance art to something of a climax. The three artists shared one thing in common: their works were driven by bodily instinct and an innate understanding of art.

Courtesy of the artist

Since chancing upon Gilbert & George, Ma Liuming began to occasionally appear in his works in the nude, eventually transforming into a semblance of the female nude. It was common for people to explain his work through ideological and cultural criticism, and due to the efficacy and so-called authority of the (Western) art history from which said criticism arose, such interpretation was widely accepted and disseminated. To be sure, this catered to art’s concurrent commercialization and industrialization, and led to the pigeonholing of artworks and the subservience of their production to confining mechanisms. Fast forward 20 years to today, when this way of explaining art has lost its effectiveness (even though some still tirelessly continue to manufacture conversations along these apparently highly theoretical lines), we seem to have lost our link to history. Ma had once described his inspirations for his alter ego “Fen-Ma Liuming”:

“The concept of ‘gender neutrality’ aims to reveal an awkward position: people judge each other using such cultural properties as clothing, rather than the innate properties of the other party. Our materialistic goals often reflect on our spiritual leanings.

“When I enter a role, I lose myself.”

The statement reveals Ma Liuming’s multidimensional sensitivity to the body, to the artist’s human body, and to his own body. He sees it much more than a mere instrument or symbol. This seemingly small opening reflects an authenticity within the artist’s world. What we glean from this one minor statement is rich, and it is this very richness that outruns the discursive potential of aesthetics.

The fate of having one’s creations standardized, labeled, disseminated, and viewed under the pretext of Modernist history befalls not only Ma Liuming, but other artists who have dabbled in performance art, including Li Yongbin, Wang Jin, Zhu Fadong, Song Dong, Luo Zidan, Yan Lei; Shanghai artists Zhao Chuan, Ding Yi, Qin Yifeng, Song Haidong; Zhang Peili, Geng Jianyi, Song Ling from Hangzhou’s “Pond Society”; Guangzhou artists Chen Shaoxiong, Lin Yilin, Liang Juhui, Zheng Guogu; and Xiamen Dada.

Several of Chen Shaoxiong’s works in the early 1990s that include performance elements, such as 72.5 Hours of Electricity Consumption and Seven Days of Silence attempt to question performance through conceptual art. They also express the existence of an individual coping with both the boredom of living in a developing city (Guangzhou), and his yearning for relevance.

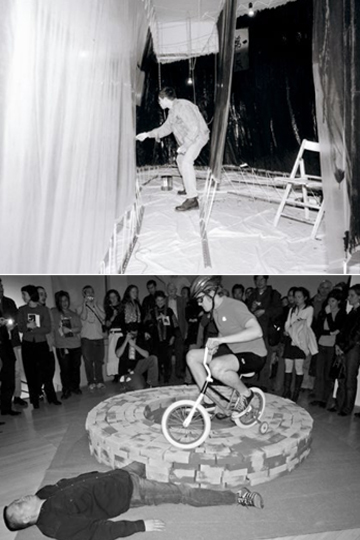

Meanwhile, Lin Yilin’s series of works involving bricks attempt to dissipate the meaning of historical constructs using the banality of daily elements. This series is a fundamental cornerstone of his entire creative career, and is closely related to his thoughts on politics and political systems. Even today, the works and the context in which they were created have yet to be seen in a fair and equal light in contrast to art itself.

That is the very focus of this issue’s cover feature. How do we avoid the trappings of the modernization of art history and aesthetics, and go back to the context that drives the artists and their practice? The term “The Performance of Creation” seeks to avoid discussions of traditional media and to enter an inner space within art creation. At the same time, due to the ambiguity surrounding the term “performance art” in China—and, while battling the traditional sense of “performance” as it interacts with aesthetics, the immediate expectations it has of the audience, art history, and the environment—the concept of “performance” is here privileged over “behavioral,” a decision that in a sense points to the political core of artistic creation.

1992, performance, installation, daylight lamp, bulb, electric

meter, wooden frame, raincoat

Courtesy of the artis

Lin Yilin, A Kind of Machine Called ‘Liberation’, 2003,

Performance, 15 min.

Today, with much of the reference and pressure from the past alleviated, we must revisit and reconsider the past with even more earnestness. Realizing the difference does not signify an in-depth understanding of that difference. Critic Thomas J. Berghuis mentions in his book Performance Art in China that we must look at performance art from a broad cultural context that looks beyond official and unofficial perspectives, to see what possibilities performance art creates for the world we live in. Unfortunately, while his discourse approaches performance art from the perspectives of medium, society, and the industry, it does not enter the true context of an artist at work to experience each and every individual encounter with its audience. Instead, he files these works away according to the standard tropes of modernity.

It is notable that some of the works being made now, using (the artists’) human bodies as their subject matter, are becoming connected again to our history, and offer an important referential point to art’s quest for introspection. In the practices of Chen Zhou, Hu Xiangqian, Li Ran, Li Qi, Liu Ding, and Yan Xing, snapshots of the body are dissected from various angles. These are as specific as they are abstracted; they follow the instincts and desires of the artist, and symbolize the artists’ position within the art profession, art history, and in the here and now, as well as represent their attitudes when interacting with different forms of the Other.

In Li Ran’s works Mont Sainte-Victoire and Beyond Geography, he appears, by way of playful imitation, as his self but not himself, thrown into various contexts and conflicts. In Beyond Geography he assumes the role of a National Geographic TV show host, and completes an adventure employing the set formats and tactics used to keep audiences engaged. Li Ran “the host” encounters an “aboriginal” tribe and attempts to interact with them. Most critics see this as a satire of imperialism, but Li intends this as a play on the fictional audience that we formulate as we set out to create art, and the common problem plaguing artists who cannot look at their creations unimpaired. In his latest work Stop Imagining, he stops playing someone else and speaks to the audience in the first person, discussing his thoughts on himself and others, and how those things are brought back to reality during his work.

Chen Zhou’s latest work I am Not Not Not Chen Zhou takes his earlier output as its subject matter, questioning his own epicurean views toward art and beauty. He plays a “desperate” man who is nearly lost in nihilism and cynicism, who avoids his peers, and attempts to wrestle the secrets of art creation from within bits and pieces of interaction.

Chen Zhou and Li Ran’s work is connected to the anxiety of creation that arises from our history by a secret passageway. Yet their backgrounds are more professional, and thus their approach more urgent, than the rest of ours.

In fact, performance must face its audience, but to enlarge this destiny to the point of apprehension, and even to lose confidence in the work itself, is a frequent occurrence around us. To establish a connection between art and other elements is not wrong. From the perspective of our history, this task has seen constant progress. But behind this excitement and celebration, we see that art has been infinitely magnified. As it progressively abandons its traditional boundaries, it establishes a new set of boundaries through purely imaginative exercises in order to prove the meaning of its existence. How should art measure reality? This old question, frequently asked within the context of Modernism, is still of tremendous significance in this latest of realities. At least for the artist, the closest reality does not sit outside of art, but within. This is not a mechanical debate on inside vs. outside or subjectivity vs. objectivity, because to our realities, too much of the “outside,” too much “objectivity,” serves only to fabricate false values and unjustified power. And taking the shape of a new order, these only serve to imprison the creative act.