ZHAI LIANG: THE WHOLE OF KNOWLEDGE

| March 7, 2014 | Post In 2014年2月号

Nine years ago, Zhai Liang called a selection of his works the “Decisions Collection.” They are small watercolors, mostly of scenes from daily life. Some include human figures and some are simple scenes. Titles such as Tian’anmen Square, Dancing to Sounds, The Ambush, and Massive Dust Particles emphasize the narrative force of the paintings. As well as the formal unity of the series, the pursuit of rich and complex content appears to be an everyday practice for the artist. In recent years Zhai Liang has given constant thought to the basic problem of painting—what subjects to depict and how to portray them. The choice of subject is one of the oldest issues in painting. Although contemporary artists are no longer restricted to religious and historical subjects, Zhai Liang takes the craft of painting seriously and is traditional in his approach. From this Zhai Liang could not glean a common theme for this group of works, so he called it his “Decisions Collection.”

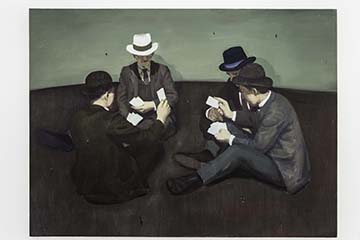

Now that the exhibition opening at White Space Beijing is over, it seems unusually quiet. Each day around noon, Zhai Liang comes to the gallery, changes into work clothes and picks up a book to read, or draws in a small sketchbook. Sketches large and small are pinned up on the green wall; some of these have already been turned into paintings. The square exhibition space has been divided in two. As you enter you are surrounded by different sized works by the artist. The most striking work is placed directly in the viewer’s line of sight. Titled There is Only One Truth, its composition and tone are reminiscent of Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. Zhai Liang has said it is a cross between Manet’s paintings and Cézanne’s The Card Players. The lower half of the wall has been painted grass-green, a soothing color for the viewer.

2013, oil on canvas, 135 x 182 cm

Courtesy of White Space Beijing

As you walk round and enter the other side of the space, the artist’s long workbench comes into view. On the wall are a number of the sketches Zhai Liang designs every day. On the bench are the artist’s tools and the Ming-era book The Night Ferry. On bookshelves above and next to the bench sit many reference books, including The Monasteries of Luoyang, Space, The Gnostic Religion, A History of Christianity, and Histoires des peintures. This behind-the-scenes view encourages us to make a connection between Zhai’s reading and his painting. In both his subject matter, which is hard to classify, and in his reading, he is unintentionally working towards a kind of knowledge, or towards the imagination of knowledge.

For Zhai Liang, reading is parallel to painting, an activity that paves a way for the difficult task of choosing subject matter. The books in the exhibition space demonstrate his interest in Western philosophy and Chinese history.

The artist has already reached a certain stage in thinking about subject matter. He wants to use

his painting to create a system of thought, and this exhibition is just a beginning. Its title highlights the intertextuality of painting and reading: “Catalogue: The Library of Babel.”

The names of the works are based on stories, but for a lot of viewers and art lovers the visual aspect alone is enough to attract them. In Zhai Liang’s work there is always something accessible that draws you in. This is especially true of his watercolors, each a simple and concise snapshot of everyday life. They suggest that there is a mystery to be found in the quotidian.

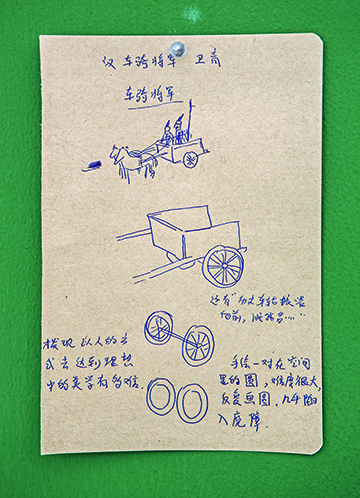

General of Chariots and Cavalry was a high military rank in ancient China, part of the Han ranking system and just below the ranks of Supreme General and Fast Cavalry. The main duty of this rank was to lead expeditions against rebels. In times of war the General took up his post; once battle was over he would be dismissed. Zhai Liang starts by drawing the chariot in his imagination, and in the process of observing the picture he starts choosing what to remove until he is left with the two wheels seen in the final work.

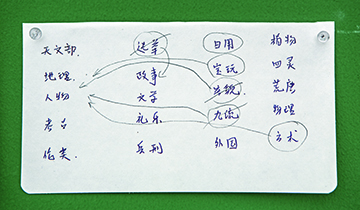

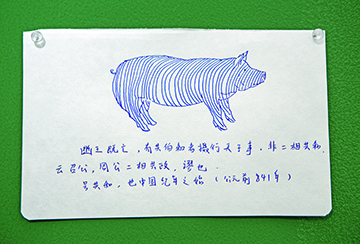

The Night Ferry is a miscellany by Ming author Zhang Dai. It covers a broad range of topics from cosmology and geography to official classics and histories, from religious thought to myth and folktales, from the politics of individual leaders to institutional history. The topics are wide-ranging and are classified into 20 main categories, with more than 4,000 entries in all. With the range of disciplines and fields of knowledge covered, it is like an ancient encyclopedia. The notes taken by Zhai while reading this book provide the raw material for many of his works.

“The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps an infinite, number of hexagonal galleries, with enormous ventilation shafts in the middle, encircled by very low railings. From any hexagon the upper or lower stories are visible, interminably.” The title of Zhai Liang’s exhibition is taken from Borges short story “The Library of Babel.” The opening sentences introduce an imaginary library to the reader. Zhai Liang believes that The Night Ferry also describes a library of encyclopedias.