THE INDIVIDUAL, TORN APART

| June 25, 2014 | Post In LEAP 27

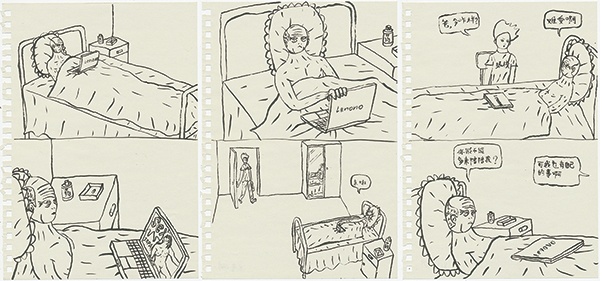

2009, ink on paper, 14.5 x 21 cm

DRAWING CONTOURS ON PAPER, Wen Ling takes his time as he creates frame after frame of images from his daily life. With no strict storyboard, Wen draws what he sees and experiences in quivering traces of ink on paper.

Say life is like one extended take. Wen Ling is aware that the memorable scenes are those images that are subjectively chosen and connected together. Through Wen’s drawings, and in particular the consciously highlighted details, I can clearly feel the artist’s state of mind at the point of creation, which is one of anxiety and contradictions. I muse over the question: has Wen ever thought of passing his pen to his father—who often appears in Wen’s work and is himself a cartoonist by profession—to discover how his father would narrate the same stories from his perspective? In what state of mind would this activity put his father?

In an interview, Wen Ling once expressed that his wish as an artist is to reproduce and disseminate his personal thoughts and way of expression, as if passing on his DNA through creating new bodies of life (art). This process is similar to how individuals augment themselves in society. With the hope that one’s own creations are singular and irreproducible, the individual strives to fortify his uniqueness and maintain a sense of freedom in their work.

In Wen Ling’s illustrated stories, a personal value system is evident. In one, he expresses disdain for his father’s prejudices when his father seeks to educate him through observing a garbage man on the street. At the same time, Wen also accepts the care of his father, as meticulously highlighted in the ruffles of his shirt when he lets his father grip his arm. Wen depicts his father as a man who is never without his laptop. For a young man, a laptop may be multifunctional and full of treasures; for his father, the computer is used solely to watch porn and thus stunt his daily sense of loneliness. The individual whose ability to care for others has not reached maturity faces the cruelties of reality with bewilderment, and finally seeks refuge in venting his shame and sorrow on paper.

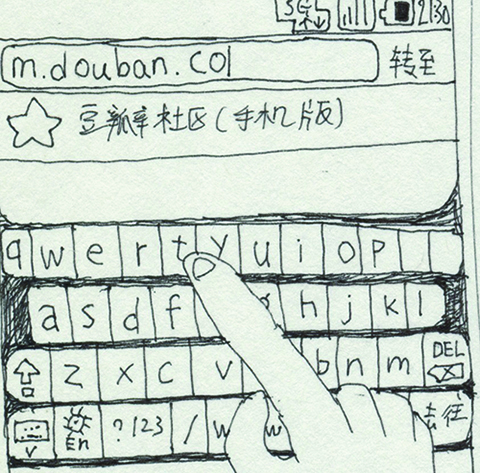

For a man like Wen Ling, who strongly desires subjective expression, drawing is the most convenient outlet. When a person’s facial expression reminds Wen of the government customs building near his house, he simply frames the person’s facial features with the contours of the building. This method is similar to paper cutting and cloth painting of northern Shaanxi province, in which facial features are spontaneously added onto kinds of good luck charms to transform the objects into bodily forms that add new meaning to the charms. To render such absurd imagery with realistic oil painting techniques, for example, would be rather laborious, and while photography or video can communicate a strong subjective perspective, it would be difficult to eliminate secondary background elements from the picture frame. With ink on paper, Wen outlines the contours of cellphone application icons while obscuring the finger that operates the cell phone as an abstract form. The possibility of such malleability allows the artist to easily express his vision by extracting forms from objective reality.

The above reflections surfaced after reading through Wen Ling’s handmade publications. Compared to publications produced with a six-digit budget and a complete editorial team, the cost of Wen’s distributable works on paper cost next to nothing.

Every time I watch laborers clumsily lift large oil paintings to hang in the gallery space; every time I see an installation fully completed in the studio, ready to be packed and shipped for exhibition; every time I witness artists crunching numbers to evaluate production costs… As I flip through Wen Ling’s DIY publications, Wen sits beside me, one arm resting on the table as he takes out a sheet of A4 paper and starts to draw me reading his book. He might depict me as a panda, who knows. To me, the situation feels especially warm and intimate.

Mainstream attention paid to works on paper does not establish a substantial connection with the development of art history, because drawing is a fundamental response to society. Drawing is an expression of disdain for mainstream art standards. I would not call Wen Ling a cartoonist, or consider his ongoing practice of sketching by hand as a kind of bad art. I would claim that Wen’s choice of medium bares an indelible mark of his time.

Wen Ling not only works with pen on paper, watercolor, and photography; he also regularly practices still life, in order to sustain the vigor in his practice and avoid certain choices becoming blind habit. Wen received formal training at Central Academy of Fine Art, where eye-hand coordination exercises were evaluated by the coherence of the depicted space to the laws of actual physical space. In school, such exercises were repeated over time to improve the students’ accuracy of expression. Wen Ling’s drawings may appear careless, but the drawing of a few lines may take a very long time to execute. He aims to highlight the essence of his subject, while at the same time considering the measure of the subject in his own mind. How does he, in his subjective mind, determine the accuracy of his drawings? He does not know: “What cannot be said clearly should not be said at all.” In contrast to academic standards of drawing, Wen Ling’s own standards, to a great degree, are established by his belief in himself.

How does an individual establish connection with other people, with society? The insistence on a one-way transmission of subjective consciousness can be praised for its rare purity, but at the same time, it can be considered an avoidance of social maturity. Of course, such stubbornness has always been applauded.

We have seen a lot of images that claim, but do not necessarily reflect, the daily life of common people, and so we yearn to see individuals who speak authentically. We have seen too much art decorated by theoretical interpretations, and so we yearn to promote the importance of narration and vitality in painting. We have seen painting (including cartoons) as too conventionalized, and so we yearn to rebel with bad art. We have read too many theories about “the death of painting,” and so we hope that young artists can prove it is still alive. We have seen too many social issues regarding senior retirement, and so we hope to see practical solutions in art. There are always people who rudely harvest fruit that is not yet matured enough to contain substantial experience of the cruel reality and its contradictions and complications.

To fully understand Wen Ling’s works, it may be necessary to see Wen’s narrations depicted from the perspective of his father. It may also be necessary to consider the visage of the viewer while viewing his works. To conceal this information and evaluate the works outside of the context of the artist’s daily emotional state, would amount to fragmenting his art into pieces. A complete view of Wen Ling’s work, with the missing pieces back in place, would be a very real and very rich sort of social portraiture. Such a painting would highlight the smallness of the individual.

The more the individual insists on an ideal, the more easily he will crack under sudden changes in reality. But only at this time might the individual’s creative potential find the opportunity to surface in the most suitable form and by way of the most suitable tools. And when these works come into being, there will be those who categorize them by style, by medium, and write them into kinds of art histories—the history of painting, conceptual art history, new media art history, performance art history, or the history of art on paper…