BLISSFULLY YOURS

| July 2, 2014 | Post In LEAP 27

Courtesy of the artist

I

There are places we end up when we don’t really belong anywhere else. This sense of not-belonging, it is naturally felt by those existing on the fringes of society. There of course is no “outside” outside of perception, and how one perceives oneself relating to the whole can elicit a sense of cagedness far worse than actual incarceration. It is a feeling that Kim Kyung Mook deeply identifies with. Dropping out of school at the age of 16, Kim moved to Seoul, where he began a career as a journalist. Like a lot of gay teenagers, he began meeting strangers, older men he’d contacted over the Internet, for sex. This has as much to do with a desire for escape as it does with a need to fulfill a sexual impulse—perhaps even more so. To exit the world via another’s body: a temporary release from the more draining and depressive banalities that constitute the day-to-day. Although money may be occasionally exchanged, it is not about necessity, livelihood; rather, exchange becomes part of the escapism built into the transaction. (It also allows for a sort of release from engagement in any emotional economy; the older man is thus enabled to remain faceless—to maintain some anonymity and withstand any feelings of guilt from the limited ability of his engagement with the younger man.) As is, in the case of Kim, the record. For he had a need to document each encounter, either in the form of a video, a written description in his diary, or, at the very least, an imprint in his memory.

Kim’s first feature film, Faceless Things, was made when he was 20 years old, and is a direct extension of these early experiences, his coming-into-being via sexual escapism. As such, the film is rendered with an unsettling crudeness—both in its content and its style—that we are more accustomed to seeing in amateur porn rather than in cinema. It is comprised of two parts, each of which is shot in a single take. In the first, a stationary camera, planted in the corner of an hourly “love hotel” room, captures the encounter between a teenage schoolboy and a married, closeted middle-aged man. The two talk for a while, then start to have sex. The man tells the boy that he needs to shower before they continue. The boy protests, but ultimately gives in. “Be sure to wash out your asshole, too!” the man instructs.

Courtesy of the artist

Back in the bedroom, the boy tells the man about an awesomely fantastic novel he is working on; the man dismisses it as Kafka-esque. The man puts on a black mask so as to obscure his face, in fleshing out a sort of rape fantasy, and fucks the boy harshly, brutally, flinging him across the room. He orgasms without bothering to get the boy off. After a few minutes of banal banter while he dresses, the man leaves the boy alone in the room, instructing him to stay behind for a few minutes so that they won’t be seen exiting together.

The boy doesn’t know what to do. He jerks off in bed for a while, but is too bored to cum. He walks across the room, sits at the desk, and looks out the window, where he sees another encounter taking place in a room next door…

This second scene documents one of Kim’s actual encounters with a john, a “faceless thing” whose head remains covered throughout with a white cloth so as to protect his identity. He has asked Kim to defecate on him, and the director has agreed, as long as he is able to film the encounter. Again, the segment is filmed with an awkwardness that matches the overall discomfort of the situation. Kim makes a few halfhearted attempts to interview the shitlover—“Have you ever eaten your own shit?”—in between failed attempts to squeeze out what the guy wants. Finally, after several agonizing attempts to perform, Kim manages to snake a long black turd out on to the man’s naked chest. “Don’t get any shit on me!” he condescends to the guy, who interrupts the process by repeatedly pawing at the young director’s anus as he attempts to finish. Kim steps back and films while the faceless scat queen smears shit over his chest and cock, masturbating himself to completion.

In trying to escape those aspects of our lives that we feel most entrapped by, we often wind up becoming victims of our own fantasies. You can’t help the way you feel; we are ultimately owned by our impulses, no matter how dark or conventional they happen to be. If Kim were less clever, he would have titled his film Shameful Things, for it is essentially a film about other people’s shame. The shame of the closeted married guy, the shame of the one with the putrid desire no one wants to fulfill. The boys, the counterparts, seem all butthole and no agency. But in fact, in each act, the younger partner becomes the face of the encounter, the obviating force of desire.

Worldly Desires, 2005

COPYRIGHT: Kick the Machine Films

Courtesy of the artist and Leo Xu Projects

II

I’ve never been to Thailand proper, though I’ve traveled there many times via Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films. Describing a place is a fairly straightforward process; evoking the essence of a locale, on the other hand, is a difficult, if not impossible task. This is the difference between journalism and art. Weerasethakul’s are soul, minus the sort of description that we have come to rely on as a means of orientation; we must find our way within the thing. It is as though we have woken up in a strange jungle—not unintentionally, the setting for so many of Weerasethakul’s scenes—and, without guide or map, must traverse our way through the dense foliage, only to finally discover, once we think we are on the verge of making our way “out,” that it has been a dream; the shadows thus cast on the banality of waking life then impregnate it with a rich mystery that cannot be readily solved, because we have to make our way through this life in a similar way as we foraged through that dream jungle.

As such, Weerasethakul’s films are difficult to understand, if by “understanding” we mean coming away from a thing with a clear, summarizable impression of what that thing ostensibly is. They contain no message, in the conventional vein. This is, in fact, what is queer about them, even though they do not always directly address issues of gender and sexuality. Much like the other directors under discussion here, Weerasethakul’s films establish that Western conceptions of gay or queer lifestyle politics have little-to-nothing to do with sexual life in this part of the world—Thailand, in Weerasethakul’s particular case.

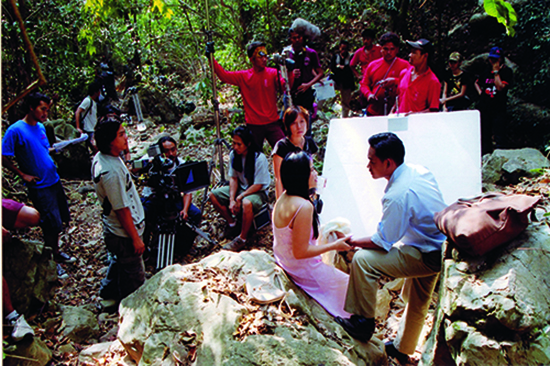

Often in Weerasethakul’s work, what is probed is cinema’s vehicularity. We get into a car, but we don’t know where we’re going, only that we are in motion and that the mechanics have been partially exposed. This process is literalized in Worldly Desires (2005). The film consists almost entirely of medium to wide shots. As is often the case in the director’s films, the jungle landscape plays just as big a role as the actors; the film is rife with frequent cuts to trees, the twisted foliage… It is a film within a film. Perhaps two films within a film. It opens with a shot of a music video being filmed in the jungle, the song “Will I Be Lucky,” in which the female singer questions whether she will find a love as strong as that of her parents. This footage is intercut with footage of another film being shot, focusing on a man who has kidnapped a woman, or perhaps he has lured her into the jungle willingly and they are en route in some kind of escape—it is hard to tell and ultimately unimportant. What matters, clearly, is the jungle—that classic symbol of untamed sexuality. The actors are hardly focused upon. Instead, Weerasethakul’s camera lingers upon the filming taking place, the crew members—the crew in the landscape, really. Midway through the 42-minute film, one crew member is heard to ask another: “Do you know this jungle has many scary tales?” He promises to tell her some of them come nightfall. Shots of crew members walking alone through the jungle, lugging equipment… Actors, soldiers, disappear into the landscape, never to be found again.

COPYRIGHT: Kick the Machine Films

Courtesy of the artist and Leo Xu Projects

It is as though the very mechanics of the jungle itself have come to be exposed, and yet they haven’t. While cinema’s machinery can be readily unveiled, we can never really understand the machinery of nature— with every layer peeled back, another mystery comes into focus.

A more explicit allegiance of the mysteries of the jungle to the mysteries of human sexuality is articulated in Tropical Malady, a feature-length film from 2004. Set in a small town on the edge of the jungle, the first part of the film is about a soldier’s wooing of a local boy. The two embark upon a sort of innocent romance, taking trips throughout the countryside together. At the moment when their love looks as though it may become intimate, the film suddenly changes into another film, a Thai folktale about a soldier (played by the same actor as before) sent into the jungle to find a villager who has been lost. There, the soldier is taunted by a shamanistic tiger spirit (played by the actor who portrayed the peasant in the first half), who eventually drives him deeper into the jungle until he is lost—to the world and to himself. This, of course, mirrors the metaphysical core of the first half of the film, completing the evocation of what actually happens when one falls in love with another person. The derangement of the senses is underscored by the confusion of Weerasethakul’s deliberately confusing script and the perpetual seeking of the camera work in the jungle. What is lost, quite often, can never fully be recovered.

Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space 2014

III

The work of Singaporean artist Ming Wong is one of the more readily and frequently cited examples of an artist’s queering of the cinematic canon. This impulse in his work can be traced back to the classical kitsch spirit of much early gay art—re-creating something and doing it intentionally badly. It comes out of an oppositional spirit, the desire to make fun of something while simultaneously asserting your love for that thing. Using humor to problematize notions of stable gender and racial/ethnic identities, Wong’s work departs from gay camp aesthetics and develops its own path of queer absurdism.

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant is, like many of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s films, a narrative of devastation. The anti-heroine, a successful fashion designer and lesbian, falls madly in love with Karin, a beautiful young woman that Petra attempts to seduce through molding her into a catwalk model. The love is unrequited, and after she is abandoned, we witness Petra’s hysterical nervous breakdown on her birthday as she awaits Karin’s call.

Ming’s “re-make” of Fassbinder’s film, Learn German with Petra von Kant, was made while the artist was preparing to relocate to Berlin in 2007. Rather than enroll in a language course, Wong designed his own “language and cultural immersion program,” using the climactic scene of the film as his nexus. While the ironic standpoint of kitsch described above may have been the departure point, there was a certain amount of pathos involved in Wong’s project. As stated in the project description on his website,

With this work the artist rehearses going through the motions and emotions and articulating the words for situations that he believes he may encounter when he moves to Berlin as a post-35-year-old, single, gay, ethnic-minority mid-career artist— i.e. feeling bitter, desperate, or washed up. (“Ich bin im Arsch”)

The screen is split into two. On the left side, we see footage from the original film, with Petra played by Margit Carstensen, a white German woman. On the right side, Wong—an Asian, non-German speaking man—plays Petra—or rather, portrays Carstensen playing Petra.

In a further “fagging out” of the canon, Wong takes Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice as his target, this time playing both roles—that of the tormented elderly writer, Gustav von Aschenbach, and the teenage boy he lusts after, Tadzio. Set against the backdrop of an undeniably twenty-first-century Venice—the characters wander through pavilions at the 53rd Venice Biennale—Life and Death in Venice again deploys the split screen, though this time footage of the original film is eschewed in order to give both characters their own space. The isolation that results from this split screen device also allows for the emphasis of the apparent absurdity of the situation, with von Ashenbach’s intense stare preserved on the left-hand side humorously contrasted with Tadzio’s aimless, wandering gaze. Unlike the boys and the men in Kim’s Faceless Things, here, the only exchange between the two is limited to glances— the boy’s furtive, the man’s obsessive and consuming.

Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space 2014

=

As we can see, the queerness of these artists’ work has less to do with their sexual orientation, and more to do with the desire to formulate their own resistance to codes of heteronormative ways of looking and perceiving. In the case of Wong and Kim, the artists’ direct involvement on-screen refutes traditional conceptions of narrative versus- documentary filmmaking, although it could also be argued that Weerasethakul is fully present as well via his constant interventions throughout his films—a disruptive presence that lends his films their rich and varied texture.

All three of these directors problematize the agency of the gaze through the filmmaking apparatus—for it is the gaze, that loaded means through which we look upon and fathom the bodies and agencies of others, that ultimately directs us in our lives. For Kim, Weerasethakul, and Wong, queerness is an epistemological problem that can never be solved. If there were any answers, then there would be no further impetus to keep making art. There is a monster that lives inside, but we cannot find it. Our attempts to confront it always end in the question, “Where?” To separate yourself from the intimacy of that confrontation, wherein the self lays down with its own demon, is to sever yourself from the projective possibility of knowing.