PIERRE HUYGHE

| March 10, 2015 | Post In LEAP 31

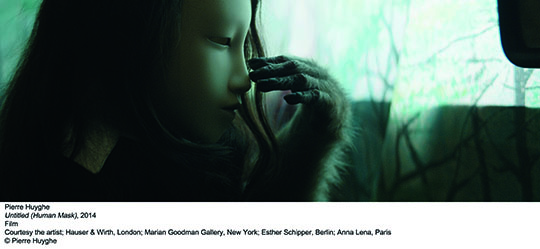

Pierre Huyghe’s latest film, Human Mask (2014), opens with drone footage of the Fukushima nuclear power plant, site of the 2011 meltdown, before settling in Kayabukiya Tavern, a modest establishment just outside the quarantine zone in Utsonomiya, Japan. Before the disaster, the tavern made headlines for its monkey waitstaff, dolled up in masks, wigs, and costumes, and trained to fetch beers and towels for patrons. In the wake of the meltdown, even this publicity stunt is not enough to draw in customers. Huyghe’s 19-minute film focuses on one of the waitresses as she navigates her newfound free time. At a loss as to what constitutes “natural” behavior, his simian heroine, still costumed, paces the dank kitchen, now overrun with filth and maggots, or retreats to the dining hall, where she sits upright on a chair, dangling her legs casually over the seat and tapping her toes while twirling a strand of hair from her wig around her fingers. From time to time, the camera catches the flash of her eyes underneath the porcelain surface of the mask, which, depending on the angle, conveys serenity or sadness. The creature is kept company only by a house cat, whose presence throws into relief the monkey’s dilemma as an animal that has forgotten what it means to be an animal.

Having debuted at a gallery show in London this fall, Human Mask joins the third and last iteration of Huyghe’s traveling retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), where it provides a point of departure for thinking about how the artist’s work functions within the museum. In an age of cynical painterly abstraction, Huyghe is a welcome rarity in his open embrace of wonder, curiosity, and beauty. His reverence for the last could feel indulgent, if not outright gratuitous, but for the artist’s ability to undercut instances of wonton gorgeousness with a cold stream of melancholia, keeping the sublime on ice. It’s the kind of work that rewards—if not requires—its audience for the willingness to open up to new ideas or experiences.

For critical convenience, Huyghe’s work is popularly lumped in with relational aesthetics, a term coined in the late 1990s by curator Nicolas Bourriaud as a way of making sense of a mode of practice in which the artist acts less as a producer of objects and more as an instigator of events or catalyst of social interactions. Twenty years after its coinage, this classification has lost its sense of urgency. Domesticated (or even bred) for the institution, relational art now operates less as a radical critique of the museum structure and more as a kind of petting zoo, peddling the chance for “authentic” interactions within a highly controlled structure specifically designed to confuse distinctions between natural and artificial habitats and behaviors. For just as the manufactured environment of the zoo is immediately recognized as an impostor, an imitation of “natural” habitat even if its inhabitants—domesticated “wild” animals—have known no other home, so too the encounters enabled within the institution are authentic in spite of their artifice.

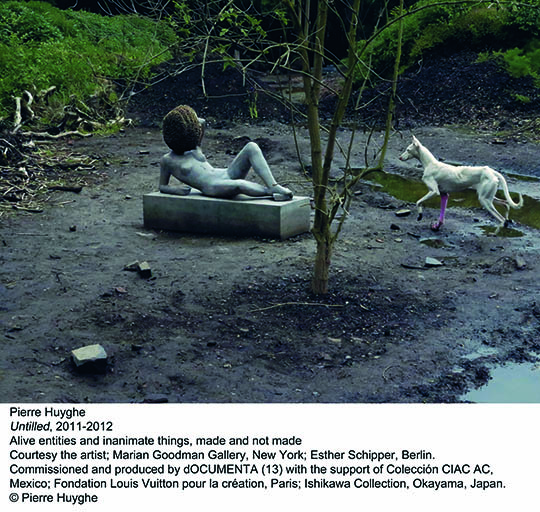

Of course, it seems highly unimaginative to speak of zoos in such close proximity to an artist who actively incorporates living creatures into his work. Huyghe’s retrospective is home to a whole ecosystem of plants, ants, bees, spiders, and assorted aquarium-dwellers, all overseen by an Iberian hound named Human, who, with one foreleg dyed fuchsia, makes a far daintier companion than the coyote of Joseph Beuys’s 1974 action, I Like America and America Likes Me, if not a dead ringer for the animated rabbit in Huyghe’s 2010 feature The Host and the Cloud. As critic Vincent Normand points out in one of the catalogue essays, Huyghe, by introducing animals into the exhibition space, rejects the de-animating tropes typical to the display of living things. Ants and bees carry on as ants and bees are wont, beholden in no way to the structures provided them (in this case, a hole in the gallery wall or a hive supplanting the head of an odalisque). The ants disappear, either deeper into the walls or off in search of a more accommodating abode. The queen bee can (and does) up and fly away, her minions soon in pursuit. The artist may have set the conditions, but he provides no assurances of the animals’ understanding, adaptation, or navigation of their new circumstance, cultivating an aura of organic unpredictability (or, to borrow the parlance of the catalogue, “potentiality”).

Of course, nothing is an easy fit. The hermit crab in one of Huyghe’s Zoodram aquariums took days to settle into the replica of Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse offered to it as a replacement shell; so too this retrospective stretched and shifted as it traversed from the Centre Pompidou in Paris to Museum Ludwig in Cologne, and now, finally, LACMA. Like the hermit crab, the show is shaped by conforming to its habitat: in this case, the Mike Kelley survey that occupied the Pompidou’s temporary exhibition hall just before Huyghe’s retrospective. The latter artist opted to keep the awkward diagonals and divisions from the previous show, which he then brought, part and parcel, to Cologne. Unable to import the original walls, LACMA constructed fresh surrogates that carve up the space like stalactites, artificially formed by a history never actually experienced.

It is not just the exhibition architecture that experiences this disconnect between event and experience. If relational aesthetics seeks to acknowledge event and object on equal footing, it also wagers that both are capable of exerting presence (or absence) on space. Indeed, much of what is on display must be reconstructed from partial traces, imprints of memories no longer tied to the objects that portend to preserve them, like postcards sent from the edge of a larger marvel. Even in the pleasure of piecing together the narratives of Forest of Lines (a 2008 project that cultivated a rainforest in the Sydney Opera House) or L’Expédition scintillante (a 2002 multi-part Antarctic epic) the viewer is left with little more than longing for an unavailable experience. This sense of loss is physically etched into the broken ice of L’Expédition scintillante, Acte 3 (Black Ice Rink): when the show opened in Paris, the piece included an ice skater who twirled in slow circles over black ice. After the ice cracked in Cologne, the dancer disappeared, leaving attention to settle solely on murky crusts of dark frost.

Ultimately, by allowing these cracks to show—quite literally—Huyghe’s exhibition acknowledges its own discomfort within the institution. For all the seductive, sublime charm of the artist’s work, it is still left to the audience to participate. In an echo of Human Mask, the retrospective rests on uneasy haunches in the museum, waiting for customers who may or may not come, but upon whose complicity the exhibition hangs.

Kate Sutton