PRACTICING LIVE: YU CHENG-TA’S PERFORMANCE AND ITS LIMITS

| February 26, 2015 | Post In LEAP 30

TRANSLATION / David East

Look at my brother. He’s successful by mastering an effective style and embellishing it with so-called conceptual content. This is why he’s known as an “international Asian artist.” Practicing LIVE , Act 2

IMAGINE A FAMILY in which each member represents part of the art world. The father is a saxophone-playing historian. The eldest daughter is the curator of a public art gallery; her son is a rising star in contemporary art. The daughter’s husband is an art critic who usually won’t shut up about one leftist thinker or another. The second daughter runs a commercial gallery, also dealing her nephew’s artworks. The grandson is a gay artist right at the peak of his career, his partner an independent curator flourishing in Europe. Finally, the uncle,(1) who lives abroad, arrives at the father’s birthday party, carelessly exposes some of the inside workings of the art world (spoiler: prices are influenced by nepotism), and sets off an argument in this artistic family.

A FAMILY OF CONTEMPORARY ART?

This story belongs to the third act of Yu Cheng-ta’s new work, Practicing LIVE, shown at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and the Shanghai Biennale. This 30-minute recording was produced by curator Freya Chou, and marks the first time that Yu’s work has taken the form of a highly structured drama. What has piqued people’s curiosity is not only the question of whether the characters refer to specific figures or people in the art world, but also whether the cast of characters extends outside the film to a complementary interpersonal network. Viewers familiar with the Taiwanese art scene will recognize museum director Huang Hai-Ming, gallery director Joanne Huang, and collector Daisuke Miyatsu. Independent curator Esther Lu is transformed into the director of a commercial gallery; the artist grandson and his curator lover are artist Larry Shao and critic Huang Chien-Hung. But the character who provides the crucial plot development is the foreign uncle, who occupies a position between collector and broker.

This transformation of identities both inside and outside the work confuses the fixed impression the average person might have of the art world. Audience members unfamiliar with the cast feel like they are watching art world gossip; after watching a Q&A session with the actors, they see a clear discrepancy between actors and characters. More familiar audience members can connect the char acters with those offscreen, shifting their opinions about the roles these performers play. Conversely, when a curator plays a gallery director, or when a scholar plays a collector, the performer’s frame of reference towards other people he or she knows is unconsciously adjusted. Actors, too, find themselves in internal conflict over specific identities. Here, the audience performs and performers spectate—the audience is everywhere.(2)

A GAME OF IMITATION

In the art world one often has to play multiple roles, causing complicated shifts and struggles within the self. As part of this world, it can be difficult to explain the precise symbolism of every character in the project: performers and viewers constantly affect one another, and cannot observe each other’s roles objectively.(3) When the viewer grasps the relationships between the characters in the film, he or she comes close to understanding how this closed system emulates the contemporary art world. In other words, the relationships in this family and the art world overlap; even if it seems closed, this circle is a microcosm of the art world, and the artist’s task is to imitate its workings.

In terms of the art world and the market, a number of conclusions can be inferred. The position of galleries appears more central than curators and critics. The gallery acts as a proxy for economic activity between artist and collector, but although it acts as the main source of feedback for the art world, it also shapes its mechanisms. Although the position of the art historian or scholar is unquestionable, contrasting plot lines allow Practicing LIVE to choose its own reality.

Putting the historian at the head of the family hints at positions of authority in the art world, but, as in any family, the head of the household does not necessarily enjoy fair treatment. The father is not familiar with many topics of conversation, gets the cold shoulder at a gathering, and is treated with an awkward silence from his art critic son-in-law whenever he speaks. Neither son-in-law nor uncle speak in Chinese, bringing about an awareness of the gap that exists between these two characters and the others. Finally, the mysterious artist David X does not make an appearance, though the exchange of his work allows the gallery to gain cash leverage from a collector. His ambiguous external orders drive the plot, a crucial missing piece in the puzzle of character analysis.

This unseen character recalls one of Yu Cheng-ta’s other works, which uses ambiguities in speech to bring about a change of perception—that of the invisible author, who is heard but never seen in the “Ventriloquists” series.

THE UNSEEN VENTRILOQUIST

During Yu Cheng-ta’s early period, from Ventriloquists: Introduction (2008) to Ventriloquists: Liang Mei-Lan and Emily Su (2009), the artist opens a political space in the small gap between personal speech and collective language.

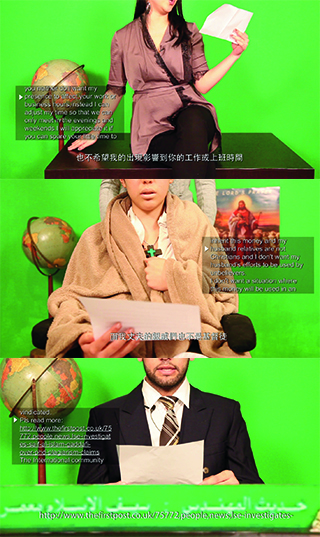

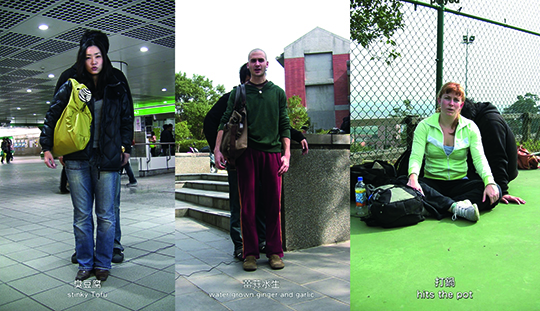

Ventriloquism is the act of disguising the source of one’s voice. In the first installment, the artist chooses a foreigner and hides in the darkness behind him, asking him to imitate the sounds of the Chinese phrases he whispers.(4) In Ventriloquists: Liang Mei-Lan and Emily Su, Yu finds two willing participants among Filipino domestic workers gathered at Taipei’s Won-Won Building, recording their responses to a number of questions about their life experiences.(5) The artist’s presence, based entirely on his voice, is outside the camera lens, showing the distance between the artist and the object of filming through the device of speech.

Ventriloquists: Liang Mei-Lan and Emily Su ends with the Filipino interviewees singing along to a backing track; whether through phonetically interpreted lyrics or at the behest of a fellow performer, they find a space to express themselves through the communication of an outsider. In “Ventriloquists,” Ode to the Republic of China, OURS·KARAOKE, and A Practice of Singing: Japanese Songs, Yu reveals himself by interpreting the language of short improvisations and personal performances. So why, for Practicing LIVE, has he expanded into a strict theatrical organizational structure? How is this shift connected to his presence or absence as an author?

IMPROVISATIONAL STRUCTURES

Yu Cheng-ta demands not only that his viewer looks upon language as a trace (in the words of Wang Po-Wei), but also that the he or she understands its capability for communication and emulation. We can distinguish between the social and linguistic characteristics of speech and script (as in Ventriloquists: Introduction) and self-expression in individualistic language (Ventriloquists: Liang Mei-Lan and Emily Su). This transformation is mirrored in the shift of feedback, from internal improvisation to structures imposed from the outside. Beginning by hiding behind a speaker and finally using a pattern of questions and answers to pull apart the space, communication remains mutual. In the dialogue in Practicing LIVE directed at the absent artist, is absence simply part of the omnipresent process of communication?

Improvisation must take place within the restrictions and structures engineered by the artist. In his own words, “Almost every one of my works is tied to what I encountered at that particular moment, and they all try to adapt themselves to the local context. But there are certain limits that exist in the works because of the nature of foreign language, and that’s why I constantly use language as a medium. I like the limitation.”

IMITATION AND IRONY

From the banter of acting in “Ventriloquists” and work like City Guide Exercise: Auckland, and The Letters, we find common ground in the restrictions placed on language. It is not the object or language that is restricted, but rather the function of the situation; the mimics either repeat what is said without thinking, or do not share the overall context of the same mother tongue with the original speakers. This kind of restriction on communication influences particular frameworks of language and sound. Here, the voice is a tool to recognize meaning, as well as a tool of demarcation. Voice becomes a clear medium of expression, even though the main restriction seems to be placed on hearing; the camera provides this medium with a framework that can be perceived through vision.

Only if the audience understands that speakers inside and outside the frame occupy different linguistic positions can true communication finally happen. Because of the improvised imitation of the artist’s framework, the audience—even if this means a laughing Yu—realizes that their position is different. The actor moves from playing a role to communicating. Our perception inevitably reaches a sort of disparity with an irony that goes beyond aesthetic rhetoric, requiring us to look into the origins of limits on form. This is what makes Yu more than a humorous artist manipulating cultural difference.

STRUCTURES OF IMPROVISATION

Practicing LIVE allows us to see a more organized Yu Chengta. This new structure reveals his ambition, though he also continues to display the presence and absence of voice in different frameworks of communication. With the form substantially intensified, he continues to explore the limits on voice, although here the focal point is more closely tied to the relationship between the audience and the absent artist.

With the symbol of a family encapsulating the autonomous system of the art world and its mutual feedback loops, Practicing LIVE is a sort of self-referencing, self-emulating mechanism in which no objective viewpoint exists. There is no real boundary around diegesis. What we see is not so much a play or show as it is life, as established in cybernetic epistemology: though the system is closed, we can still interact with it through certain nodes. For instance, amateur acting skills and mistakes in the script indicate the discrepancy between actor and character, through which we identify the loop of acting, feedback, and communication to which we belong. Satire gives way to an order of recursion, where the game of imitates reality and reality imitates itself.

When the curator critiques a certain style of work in the film, which artists do viewers think of? Who does the artist himself think of? Though Yu Cheng-ta never appears, he is never absent from communication. He participates in every single aspect of this family—gravely or jocularly—but never declares his own stance. He plays games with everyone, while we have all see ourselves portrayed.

(1) In English the term “uncle” is clear, but the artist does not specify whether this uncle is the brother of the mother or father, or why a Taiwanese family would have a foreign uncle in the first place, though the absence of the mother leaves room to imagine. The audience can decipher the symbolism of this absence and, at the same time, see the uncle as her foreign brother.

(2) In fact, those who see the piece at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum are all in some way part of the Taiwanese art world; if not players themselves, they at least have an interest in contemporary art. Even if one only occasionally visits art galleries, one is temporarily drawn into the ranks of this closed circle through the candid interviews simultaneously displayed.

(3) Cybernetics expert Heinz von Foerster amends the basic concepts of the natural sciences as follows: the observer is not absolute, but rather exists relative to the point of view of the observer; the observer can influence the observed, which can confound his or her predictions. For further reading, see Bradford Keeney, Aesthetics of Change, The Guilford Press, 1983.

(4)See Wang Po-Wei’s “Between Voice and Communication: On Linguistic Performativity in ‘On Set in the City.’” On the question of the performance of language, Wang writes: “The artist prefers nonnative speakers. Using a language with which they are unfamiliar, the feeling of alienation creates astonishing results.” Huang Chien-Hung, furthermore, writes in “The Topological Diplomacy of Voice: On Yu Cheng-Ta’s Speech-Art” on the diplomatic way in which Yu creates a collective, reconstructed space extending across national boundaries.

(5) Huang continues: “No longer hiding himself behind the bodies of the ‘spokesperson,’ asking them to relate fabrications based on their identity or situation, and no longer standing in front of the spokesperson (who is at the same time the interviewee), he hides behind the camera lens to ask questions… slips in languages no longer happen in vocal ‘brain-racking’ outside of meaning, but instead in ‘direct confrontation,’ in the mingling and ‘bum notes’ that appear when language is used to express meaning.”