GRAFFITI

| July 9, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

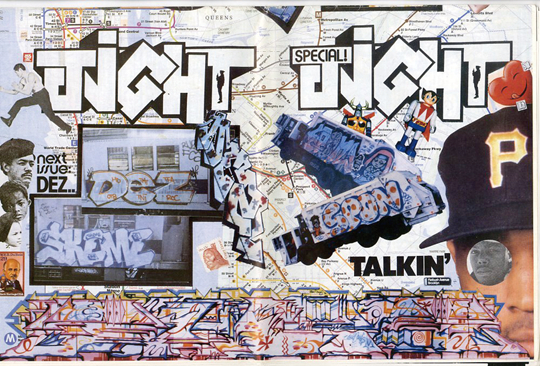

Courtesy Museum of the City of New York

Last year, when the pseudonymous French street artist Invader touched down in Hong Kong, his iconic tile minions appeared on several dozen facades throughout the city. Many were removed overnight, and the rest were invariably scrapped and sandblasted away within the week. Then, in May this year, documentation of the covert operation was exhibited at PMQ in Central as part of the French cultural festival, Le French May. Whether or not the work maintains its original fervor is up for debate, but the ballad of public versus private is emblematic of the boundaries that street artists continue to confound and elude.

Largely viewed as the defiling of private property—and thus wholly illegal—graffiti at its best is a subversive medium. Questioning the rationale of the privatized and controlled, it has the power to reclaim parts of the city, a democratic medium to which anyone can have access. At its worst, graffiti is appropriated by neoliberal development schemes, used to populate barren tracts of the urban landscape in the name of capital, christening them for speedy demolition and redevelopment. When domesticated in gallery spaces, graffiti runs the risk of losing its potency, yet it still teaches us something about the ongoing (and often coterminous) cycle of creativity and renewal.

The Museum of American Graffiti was founded in

New York’s East Village in 1989 by Chinese-American artist Martin Wong, the same year that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority declared the subways to be free of graffiti. Wong, who amassed dozens of works on canvas, wood, Masonite, and other writable surfaces, donated his collection to the Museum of the City of New York in 1994, where it sat for some 20 years. Last year, “City as Canvas: Graffiti Art from the Martin Wong Collection” opened as an homage to the late-1980s and early-90s of New York, a time before areas such as the Lower East Side were completely transformed by gentrification and development.

When Wong inaugurated his archive, graffiti still operated on the fringes. The “aerosole hieroglyphics,” as he liked to call them, evidence a space of limitless possibility. The fact that most of these works have no in-situ counterparts remaining indicates the triumph of the developers and law enforcers who colluded to make the city livable for the privileged and elite. Still, Wong’s collection (and the memory of Wong himself, a painter, avid collector, and advocate of the Nuyorican arts movement who died of AIDS in 1999) is testament to all that can happen through the bold exercise of the right to the city.