INTERNET RAP

| July 13, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

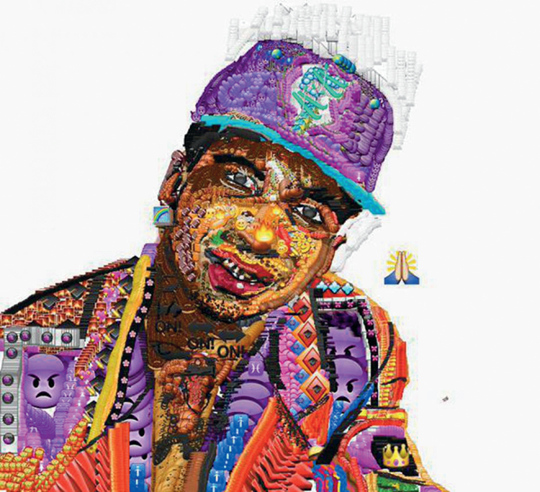

Click to play the internet rap playlist specially commissioned for the issue Two years ago a video surfaced online of a not-entirely-confident-looking Scandinavian teenager in a bucket hat and windbreaker rapping about “peeing on old people’s houses” over a loop of new-age singing and rattling drum machine beats. Now boasting more than four million YouTube views, “Ginseng Strip 2002” introduced the world to Yung Lean, the 18-year-old Swede at the epicenter of the nebulous movement that might be dubbed internet rap. The unholy offspring of psychedelic strains of American hip hop like Southern trap, suburban ennui, post-internet art, high fashion, and DIY ethics, internet rap has unleashed waves of bizarre music from prodigiously young, often white artists. Spreading through social networks and sites like the blog of streetwear store Mishka NYC, internet rap presents a topsy-turvy world of hip hop where co-signs from clothing designers count more than hits.

In their ersatz digital synths and obsessions with Japanese characters and the anonymous Asian metropolis, there’s a connection between internet rap and vaporwave, the intentionally unsettling ambient music that critic Adam Harper links to critiques of accelerated capitalism. Indeed, Yung Lean and his Sad Boys crew have posed for photos with cult drone and vaporwave musician James Ferraro. Yet, even as vaporwave aesthetics slowly infiltrates popular music and design, part of what makes internet rap so strange is how close it is to the mainstream already.

Mainstream hip hop in the United States sounds as experimental as ever, and its stars are just as plugged-in. Chart upstarts rise to the top via online hype, free mixtapes get downloaded, and stars arrange remixes over Instagram wearing the same crisp, monochrome sportswear that internet rappers cherish. There’s not that much separating the music videos for viral hits from Yung Lean’s own early videos—the former aims for slickness but falls a few notches short, while the latter accepts the impossibility of looking professional, playing around with low-resolution digital images and VHS-style filters instead. While Lean’s recent songs go for high-definition slickness both musically and visually, earlier efforts read almost like a parody of aspiration, realizing success was unlikely but trying anyway if only for a laugh.

This goof iness, a strand of self-conscious humor, is what distinguishes internet rap from the mainstream. Internet rap dares you to take it seriously, from the stream-of-consciousness rants of Lil B (a progenitor of the scene) to “My Circle,” a song in which teenage DIS Magazine contributor Glasspopcorn raps about the social network Google+. There’s always been an element of absurdist humor in hip hop. White suburbanites have been making hip hop for decades, but rarely have their obsessions and imagery so closely mirrored the mainstream.

The fact that internet rap often

actually sounds good pushes it beyond a semi-ironic punchline. Rapid-fire trap beats, string-like synths, and pitched-down samples take the textures of vaporwave and make them emotionally affecting, at once melancholic and danceable. And the game is globalizing: the manic energy, Bape shout-outs, and crude digital effects in the video for Korean rapper Keith Ape’s viral hit “It G Ma” share chromosomes with internet rap, while London-based Ecuadorian rapper Blaze Kidd adds influences from grime and romantic Latin music to tracks with Yung Lean associate Bladee. International sad boys unite.