Chen Tong: The Anti-Realist Time-Landscape

| November 9, 2015 | Post In LEAP 35

Chen Tong’s practice is anti-realist in attitude. He believes that an artist should separate the making of art from considerations of personal livelihood. Under conditions of separation, the artist can then work on the basis of detachment from reality, even if he chooses to adopt representational or other apparently realist means of expression. Ideas of survival and realism are both ideas of the mind, fundamental concepts and attitudes with pragmatic concerns. Most people evaluate their actions according to how effective they are. Some artists claim that their work is useless, but adopt a pragmatic attitude toward daily life. Chen believes that this practice remains bound to the basis of realism; in his own work, he often performs useless activities in both useless art and in lived reality.

American philosopher Richard Rorty summarizes his research in pragmatist modern philosophy with the statement that it is the pursuit of usefulness, not truth, that generally drives the progress of human knowledge. Chen’s practice goes against this view, inviting the audience to look at reality with clear eyes driven by no other motives. His choices of material and media are not guided by pragmatic concerns as an artist. In China today, every artist knows that, to make art, he should follow the existing highways of efficiency: adopt a contemporary medium, such as installation, video, or performance, and choose a form of contemporary imagery, be it abstract, cartoonish, or stylized. The trending term “contemporary ink art” is intended to legitimize an otherwise controversial way of art; it is an attempt to neatly connect to the main roads sanctioned by the art world. And yet Chen’s painting does not follow any standard genre logic, and cannot really be considered new ink painting.

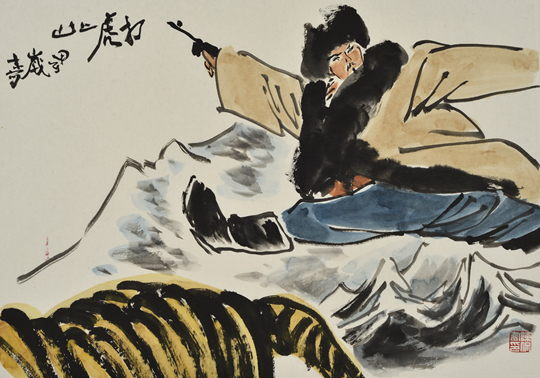

What should contemporary ink art depict? What scenes are not suitable for this genre? These questions are hard to answer, and yet many artists, by social instinct, seem to be able to determine the collective choices and taboos. Chen Tong’s most interesting works are precisely those that break these normative boundaries.

In the past, classical painters typically concentrated many events into a single framed moment. Take The Last Supper, for example: the relationships between Christ and his disciples are illustrated by multiple events occurring in different moments in time. From the painter’s hand to the audience’s gaze, the making of the painting is a historical process, and the completed work shows a network of relationships that speak towards a shared physical truth. If painting is about depicting scenes captured in still moments, I consider representational painting a “time-landscape.” In classical painting, narratives often include visual signs expressing the artist’s thoughts and observations. This kind of art appears somewhat simple for the ever-changing information age we live in today. In Chen Tong’s work, one cannot easily draw clear connections between the signs depicted and reality. Here we can highlight two features of Chen’s anti-realist way of painting. First, his early research into sequential drawing has had a strong influences on his choice of moment in time that become landscapes. Second, his painting rejects the idea that art should serve a pragmatic function, and so lacks a romantic quality.

When paintings fail to meet the expectations of the audience, the viewer easily slips into a casual, lighthearted, and wandering state of imagination. Chen Tong is a liberal intellectual, but his portraits of political figures do not show approval or disapproval of their subjects. Some critics believe this is Chen’s critical response to the conventional role of art.

In China, realism is usually discussed as an ideology related to collective consciousness and pragmatism. While Chen’s work touches on the non-real, he struggles against the realist norms of equating usefulness with knowledge. His paintings probe the relationship between human consciousness and practicality, delving deeper into these concrete relationships and surpassing overly general discussions of existence and consciousness.

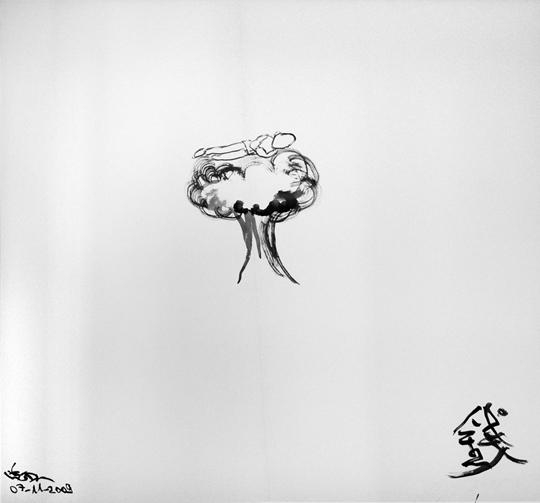

During the making of Qian Xuesen, a site-specific piece, Chen drew inspiration from many unconnected media sources. A television broadcast of an old film reminded him of the explosive destruction of Wuhan’s Yangtze River Bridge. Reading the daily newspapers also had an effect on the work. Social norms tell us that an understanding of reality requires a systematic, continual study, and only by amassing a good deal of context and information can one effectively understand the world. Chen’s haphazard collage style of piecing together mass media information appears ineffective and unserious, and would not normally be considered a good understanding of reality. In my opinion, Chen’s method questions precisely the idea of effective knowledge and learning. Particularly in this age of constant information explosion, many people avoid addressing the question: when knowledge is published at increasing speed, how does understanding work? Can one understand the world through Chen’s approach to fragmented, readily accessible information? Or is this passive, negligent method of gaining knowledge simply what we, as cultural workers today, are forced to adopt?

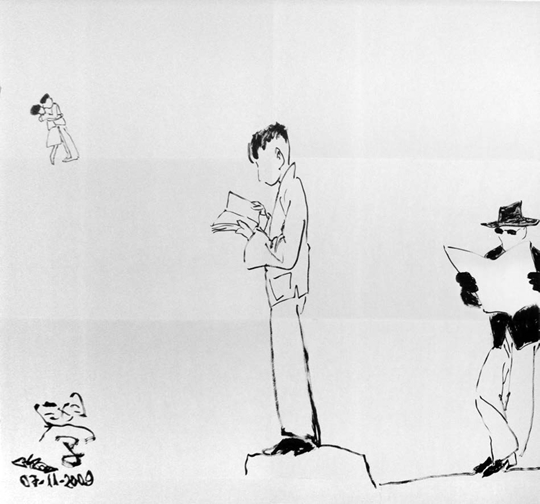

The symbols and forms of Qian Xuesen include a mushroom cloud, a ladder leading to a destroyed bridge, a forest, and a college campus with student couples. As a direct interpretation of the work’s title, a reference to the name of a rocket scientist who emigrated from China to the United States, qian (money) is expressed by a small figure lying on the mushroom cloud, rendered with traditional cartoon forms and a minimalist style echoing Feng Zikai. The second character of the title, xue (study) is literally demonstrated by a person studying a book. The third character, sen (forest) is expressed as a forest area, the illustrated form of which resembles the pictographic character itself.

These linguistic methods of interpretation are often employed in the Chinese folk culture tradition. For example, Qi Baishi painted fish (yu) to illustrate the meaning of another character also pronounded yu, for “plenty.” In Chen Tong’s work, the realism of the painting tradition is far more important than that of the real world. Even though he frequently expresses his strong opposition to the traditional use of pictographic and homophonic interplays, he uses the very methods he opposes in order to address an unspoken and firm rationale behind realist painting. A painting that literally interprets its title is easily accepted and understood. It is our inclination to stop thinking or looking further once we understand what is in front of us. This inclination is a result of our pragmatism.

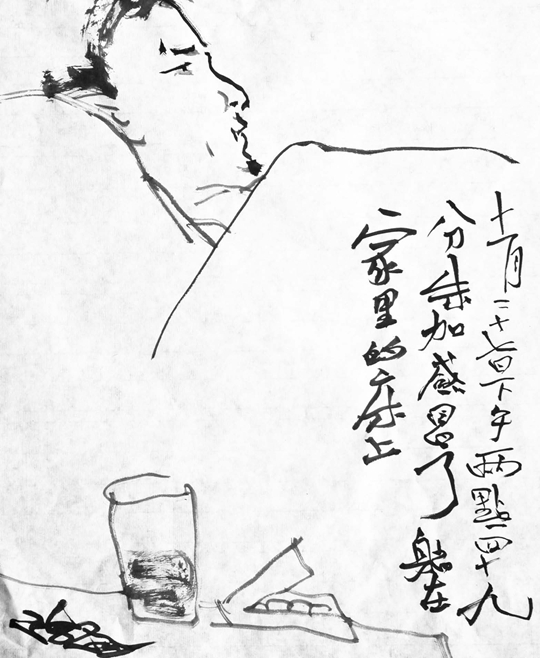

For many people, the events of the everyday and the environment we live in constitute one’s reality. One person’s experiences do not serve as a general guide for a society; to the contrary, a society of people develops its common sense through mutual influence within the frame of a shared collective consciousness. When a person develops an understanding of reality, there is also a natural desire to surpass the present state of things. With a romantic wish for change, the apparently matter-of-fact laws that govern common sense can be challenged. For pragmatists with romantic inclinations, personal incidents are not considered suitable painting material. Chen Tong’s series “Making a Phone Call” documents his friends at the moment they pick up his calls. His impressions of these moments are quick sketches in his mind, dependent on limited audio clues and descriptions given by each friend on the other end of the line. The telephone line is a medium for exchange and, like every other medium, it brings different filters to reality, and thus creates a unique dimension of being. Two people who engage in a phone conversation accept the telephone’s filtered reality without hesitation.

Looking at Qian Xuesen and the “Phone Call” series in the context of today’s information explosion, we find a pattern of reliance, convenient information sources and increasingly fragmented information. This state of things is far away from building a whole, continuous, systematic system of knowledge. Without reservation, Chen Tong exposes his method of the spontaneous collection of partial information fragments. In this process, his paintings become a medium for contemporary consciousness.

Text by Xu Tan

Translated by Sheryl Cheung