Jamian Juliano-Villani: Digital Palette

| March 31, 2016 | Post In LEAP 37

Courtesy JTT New York, Tanya Leighton Gallery and the artist

Jamian Juliano-Villani’s website is structured along the lines of popular blog host Tumblr, fittingly resembling the countless blogs that catalogue images of contemporary art and online ephemera. The 28-year-old New York-based artist’s name sits in gothic font layered over a stream of images, an animated GIF to the side showing a creature dunking its head into a swamp ad infinitum. Scrolling through the wave of macabre yet oddly humorous images, a blow-up doll playing the piano surfaces along with several melting faces and robots. It takes time to recognize the pictures as the work of one artist; they appear to be scans from vintage science fiction magazines or Photoshop fantasies picked up from a dark corner of the internet. It is not inaccurate to detect these influences on Juliano-Villani’s work, but she doesn’t directly use found materials in her pieces or edit them digitally. She primarily paints, taking inspiration from preexisting images yet recreating and recombining them by hand. Her approach poses a fascinating and contradictory question for how it references digital media while remaining defiantly analogue, even if it is often disseminated online.

In Juliano-Villani’s world, American psychedelic animator Ralph Bakshi and the French high-tech horror comics of Heavy Metal magazine sit alongside fashion magazines, biology diagrams, and Jamaican reggae illustrator Wilfred Limonious. Though she also draws inspiration from screenshots, Juliano-Villani sources many of the images she wants to work with from her extensive book collection, digitizing them and projecting them over canvases as she works.

The process of painting from projections is hardly new, but the aesthetic influences Juliano-Villani sources (and how she finds them) are intriguing for someone of her generation. Her appreciation for Limonious’s album covers ties into her self-professed love of reggae and dancehall, especially recordings of 1980s sound clashes (live competitions between singers and DJs). Juliano-Villani points out connections between the creativity from necessity that fueled reggae and her desire to paint in order to express herself beyond words. A further comparison could be made between reggae’s meshing of innovative recording techniques with the human voice and Juliano-Villani’s own combination of technology and the handmade.

Courtesy JTT, Tanya Leighton Gallery, and the artist

What is most intriguing about Juliano-Villani’s relationship with reggae, and her other obsessions, is how it reflects the internet and digital media without explicitly referencing the materiality, or lack thereof, of the media. The artist was a young child in New Jersey when the reggae bootlegs she devours were recorded, and, though often found in books, her source images are still modulated through a computer screen. This does not diminish Juliano-Villani’s affinity for her inspirations; it is simply how media is consumed now.

Courtesy JTT, Tanya Leighton Gallery, and the artist

Rather than engaging with the self-consciously of-the-moment stock approaches and visual signifiers emerging around internet art, Juliano-Villani uses the internet as a research tool into past experiences that might otherwise be inaccessible. This approach might feel slightly anachronistic, using computers to organize pre-existing images and symbols rather than exploring the new culture created by our digital existence. Yet the collage of references that fills Juliano-Villani’s paintings would perhaps be harder to appreciate if viewers weren’t prepared by the internet’s hyperlinks and barrage of images. This is painting that is best understood through an internet mindset.

Compared to other painters with a breezy approach to image appropriation and a digital element to their work, Juliano-Villani’s end results feel significantly warmer, even more humanistic. The intended effect of mixing fashion advertising and underground cartoons with elements of Bruce Nauman photos is not to wow viewers with references, but to make the paintings more accessible to someone who might be intimidated by work drawing exclusively on canonized high art. In contrast, Richard Prince’s series of Instagram paintings, though possessing a rationale of their own, can mostly seem focused on mocking users of the photo-sharing service.

Courtesy JTT, Tanya Leighton Gallery, and the artist

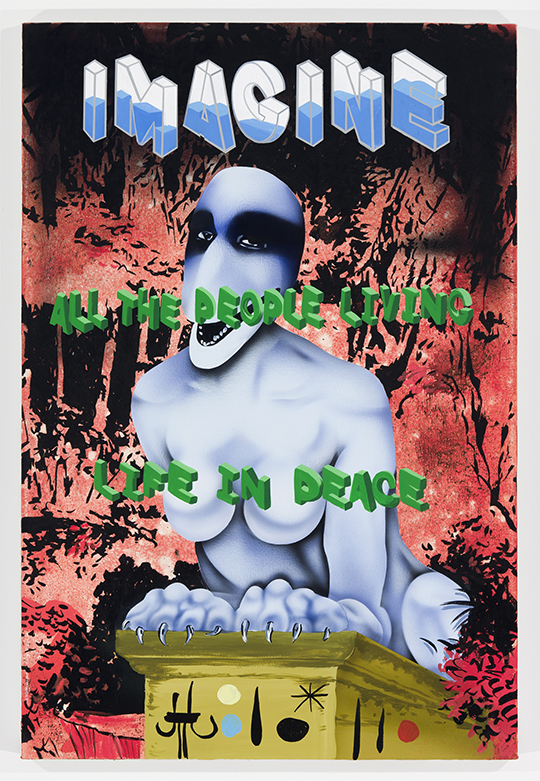

Like Prince, Jamian Juliano-Villani has also dealt with accusations of image appropriation. In the beginning of 2015, she raised the ire of artist Scott Teplin for copying text and a font from a mural (of which she had posted a photo on Instagram) in her painting Animal Proverb (2015). Responding to the controversy in a Facebook comment, Juliano-Villani stated “1) once an image is used, it isn’t dead. it can be recontextualized, redistributed, reimagined. 2) It should have several lives and exist in different scenarios.” Considering the text consisted of lyrics from John Lennon’s “Imagine,” these are justifiable claims.

Acrylic on canvas, 289.56 x 518.16 cm

Courtesy JTT, Tanya Leighton Gallery, and the artist

Recognizing an element in one of Juliano-Villani’s paintings can be shocking, causing one to wonder if she really is passing off images as her own. One of the main compositional elements of the triptych Some Deaths Take Forever (2014) is a chainmail-gloved hand holding an extinguished candle, originating on the cover of a 1980 album by obscure French electronic musician Bernard Szajner. Without context, it might seem that the artist appropriated this strange, oddly powerful image, which originally accompanied music commissioned by Amnesty International to support death row prisoners. In fact, Juliano-Villani is a friend and collaborator of Szajner, and the piece is one her most overtly political. Each panel is the size of a cell at Alcatraz, commenting on the deprivation of incarceration. Wisps of smoke trail across the dark canvases to a shining candle, a composition more affecting than the original squared-off album cover.

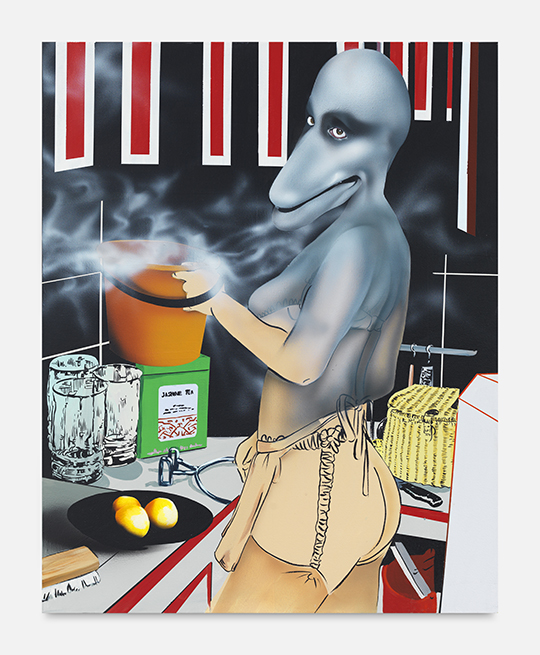

Juliano-Villani’s oeuvre relies on her ability to paint her chosen images precisely enough to make her strange fusions believable. But even though textures like the chrome-like skin of a dolphin-headed woman in Stone Love (2015) are fascinating, the viewer’s focus is rarely on the artist’s painterly technique. Instead, the viewer is drawn in by how the densely packed, noisy, and always interrelated media landscape of the present ends up translated into a decidedly human, hands-on format.