The Racing Will Continue, The Dancing Will Stay

| July 23, 2019

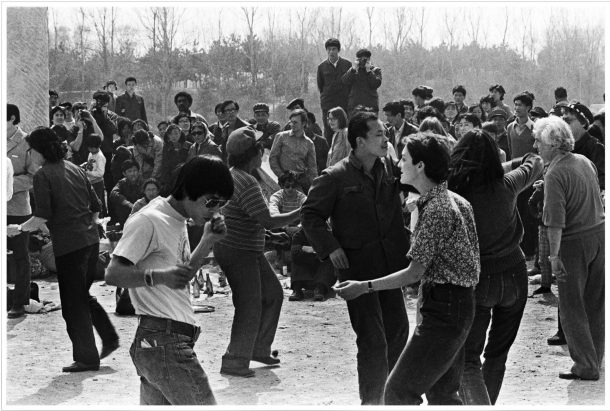

The group show “The Racing Will Continue, The Dancing Will Stay,” held at Times Museum, provides spectators with a socio-historical thread connecting together the 40-year process of reform and opening-up, the return of Hong Kong to China, the setting up of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao “Greater Bay Area” and other momentous events closely linked to the Chinese Mainland and Hong Kong. Curator Leo Li Chen has made “dancing” into the crux of the exhibition, which becomes apparent in the dance-and body-themed performance artworks and video artworks which make up a large proportion of the exhibition. The exhibition’s title is a reference to the sentence “The Racing Will Continue, The Dancing Will Stay,” an interpretation of the “One Country, Two Systems” principle formulated by Deng Xiaoping during the signing of the “Sino-British Joint Declaration” in 1984. He coupled back the effects of a groundbreaking social event to the daily lives of the people. The phrase became widely disseminated as a popular adage from the 1980s onward. Furthermore, around the time the “reform and opening-up” policy was introduced in Mainland China, “dancing” served as a barometer of the changes in the country’s political environment and prevailing social mood. An iconic series of photographs taken by Li Xiaobin in Beijing from 1978 through 1982, along with Hao Jingban’s video work documenting the artist’s research on the history of “ballroom dancing” from the 1950s to the 1980s both tackle this phenomenon head-on.

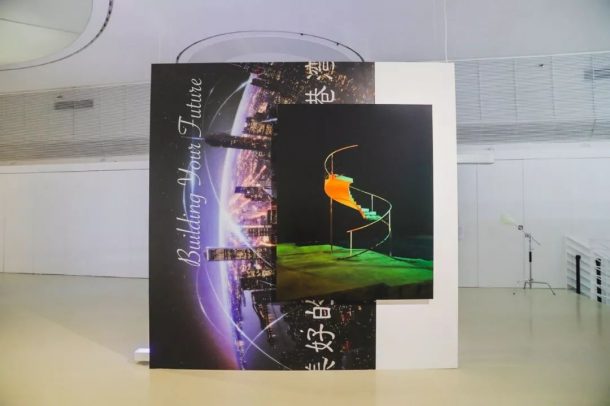

Installation: wallpaper, plasterboard, aluminum, iron, LED display, controller

Installation view at “The Racing Will Continue, The Dancing Will Stay,” Times Museum, Guangzhou, 2019

Without a doubt, the primary narrative of this ambitious exhibition has a very direct effect, in that it takes into consideration the perception by the general public, while encompassing works of artists who came of age against the backdrop of different eras, from the post-1950s to the post-1990s. However, in order to better comprehend the works of the 24 participating artists and collectives, hailing from the “three Regions on both sides of the Strait” (i.e. Greater China) and abroad, as well as the connections that exist among them internally, it’s necessary for us to uncover threads that are more covertly implied in the respective works. This leads us to “the body” as entry point into the exhibition’s subtext.

Spring of 1979, the fashionable youth swing dancing in the Summer Palace, Beijing

The system’s conditioning of the body is hard to go around in the context of collectivism. Juxtaposed in this exhibition are three video works and installations which all touch on this topic. Xin Yunpeng’s video work depicts the military boxing drills of a male high school student from Beijing as he undergoes his military training. This uniform method of instilling discipline has gone on and remained unchanged for several decades. Gao Lei, in turn, utilizes nylon material used for making prosthetic limbs to simulate the shape of the human spine, with which he reengineers a set of parallel bars used in military training, i.e. an object representative of getting in shape, backed by a nationwide physical education system. Former Chinese female tennis player Hu Na applied for political asylum while attending a tournament in the U.S. in 1982, the artist Wang Bo quotes from Hu Na’s autobiography and contrasts it with the decision of tennis player Li Na to “fly solo”—quitting the national team and absconding from the state-run sports system—25 years later. In so doing, Wang Bo sheds his light on the changing currents of our times, through individual choices made by athletes amid a tussle with their nation’s system, and the ensuing response of the public at large.

Video installation, dimensions variable

Installation view at “The Racing Will Continue, The Dancing Will Stay,” Times Museum, Guangzhou, 2019

Meanwhile, the delicate yet nimble body also acts as a platform for resistance. Placed in the same area as the previous three works, is the work by Yu Cheng-Ta titled adj. Dance, a representation of the body’s “resilient” flexibility and malleability. It can take on a “legal” straightness and orderliness, it can vibrate intensely in a way that is dangerous, or even free and unconstrained. In his work Muted Lion Dance, Samson Young has managed to remove another sound of the system, i.e. traditional drum beats. Instead, he amplifies physical traits by bringing to the fore the breathing, whispered cues and rustling feet of the musicians. Also on show is Aware-of-Vacuity, a performance art piece by Isaac Chong Wai. Inspired by the Monkey King in the classical novel Journey to the West, the artist uses metal rings and batons as props to give expression to resistance of the body. In the performance during the opening, several dancers held in their hands clumsy, hard-to-wield props as they moved around, causing resistance to form between the dancers and their props, the dancers respectively, as well as the dancers and their audience. This same resistance was also manifested between the dancers and the invisible, larger space surrounding them.

Performance, stainless steel, fabric, and sound by Nobutaka Shomura

Performance view at “The Racing Will Continue, The Dancing Will Stay,” Times Museum, Guangzhou, 2019

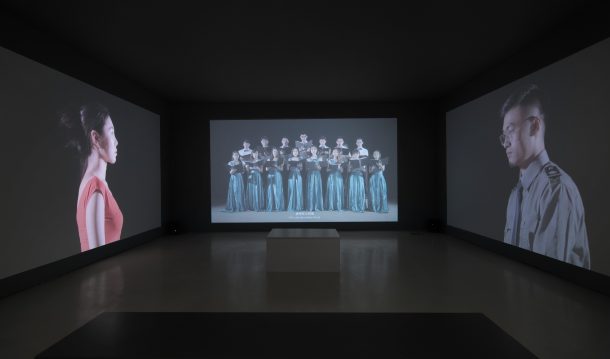

At times, the body also becomes a personification of the system, as is the case in Yao Qingmei’s Molt (Body Inspection). A musical drama in the form of a physical inspection, made up of security inspectors and female dancers, is performed live. The security officers wear uniforms that symbolize order and authority, yet they put on a comical performance accompanied by sacred- and solemn-sounding choral music, culminating in a covert feat of physical resistance.

Yao Qingmei, Molt (Body Inspection), 2017

3-channel HD video color

Installation view at “The Racing Will Continue, The Dancing Will Stay,” Times Museum, Guangzhou, 2019

The body doesn’t just refer to the human form per se, it also takes on other forms by way of extension. In Liu Chuang’s work Dance Partner, two white cars become extensions of the body as means of transportation. The two cars drive side by side from morning till night through the streets of Beijing at the minimum speed limit, causing a great deal of inconvenience for other road users, leaving them no choice but to trail behind them at a snail’s pace, overtake them or change lanes. However, both cars remain indifferent to their surroundings, since their behavior is entirely legal. This here is a daring yet conservative provocation of the lines drawn in the sand by the established system.

Single-channel video, HD, stereo

10 min 30 sec

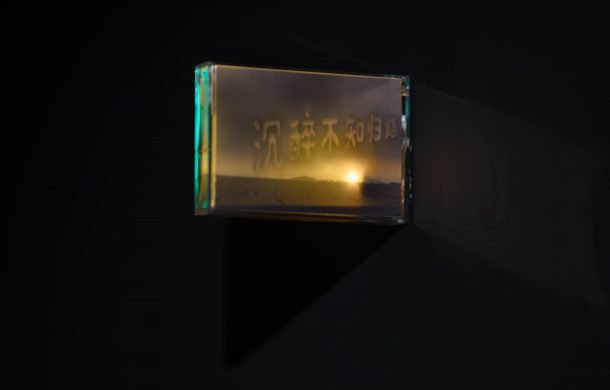

The unease and tension felt by bodies in the urban spaces they inhabit, can also be felt in the exhibition. South Ho Siu Nam’s photography series “The Umbrella Salad” documents Hong Kong’s urban space throughout September of 2014. In her painting Express, Ko Sin Tung uses a computer-generated simulation of the Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong Express Rail Link terminal to visualize her dubious imagining of an idealized vision for the future. For her work Hoi Kok, Xiaoshi Qin chose an image of the location on Shenzhen Bay Bridge where cellphone signals get switch from Mainland China to Hong Kong coverage, and vice versa.

Installation: cassette box, LED lights, digital print on gel, 10.7 × 7.2 × 1.6 cm

Also on view are a group of works that explore performativity and subjectivity. The documentation provided, along with the artists’ live performances throughout the duration of the show will afford a better understanding of these works: Li Ran’s installation New Neighbor made in reference to the 1984 stage play Good Fortune Building; Musquiqui Chihying and Liang-Hsuan Chen base themselves on the defensive Taoist hand gestures featured in the 1985 horror comedy hit Mr. Vampire; and lastly, a work by Jasper Fung involving live electronic music improvisation.

Installation: wood & metal frame structure, stainless steel anti-skid board, marbling wallpaper, literature and other mixed ready-made materials

600 × 400 × 400 cm

Installation view at “The Racing Will Continue, The Dancing Will Stay,” Times Museum, Guangzhou, 2019

On the whole, in an age of increasingly volatile political visions, this exhibition may be regarded as a positive attempt to tease out and touch on issues that despite their day-to-day palpability aren’t brought up all too often. The majority of works on show are by artists born in the 1980s and 90s. Although the artists’ treatment of historical documents and grasp on sociopolitical topics can sometimes seem stiff and overly didactic, the focus on dance and the body as thematic lynchpin somewhat mitigates this perception. Rather than merely staying on beat, this exhibition is a choreography composed of elements of improvisation and reinterpretation. Its disorderly rhythm might even act as a fitting segue to what is to follow. (Translated by Sid Gulink)