Cui Jie: Lines of Flight between Surface and Model

|

“Substance for a writer consists not merely of those realities he thinks he discovers; it consists even more of those realities which have been made available to him by the literature and idioms of his own day and by the images that still have vitality in the literature of the past. Stylistically, a writer can express his feeling about this substance either by imitation, if it sits well with him, or by parody, if it doesn’t.”1

In the opening part of their book Learning From Las Vegas (1972), authors Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour quoted as above from Richard Poirier’s appraisal of T. S. Elliot’s use of image superposition, spatio-temporal intertwining and other means of expression in the seminal book Wasteland (1922). The quote was meant to encourage architects to adopt an inclusive, non-chip-on-the-shoulder attitude, so they could derive simulations of reality from the existing landscape and reconstruct reality by means of representation. Amid a wave of postmodernism, this full-fledged approach of developing and utilizing the value-in-exchange of symbols caused a breach in creative barriers between art and architecture, and cast light on the way in which modernism captured pure form. In particular reference to urban construction and development, the interchangeability of the identity of artist and architect is instrumental in pushing the notion of space towards a dimension verging on democracy. In this vein, Cui Jie, an artist who came of age in the 1980s and 90s, shows a keen grasp on the various architectural patterns that have had a profound effect on the rapid renewal and expansion process of Chinese cities, and is adept at selectively harking back to these precedents of modernization in her painting and sculptural practice, thus triggering a momentary sense of the immediate future. The architect’s psyche reflected in her work goes beyond a mere collage-like schematization of architectural elements. Instead, her works are predicated on a technical enthusiasm for the city’s “autonomous surface” (hereafter referred to as the “epidermis”) and a pattern recognition of geographical misplacement or anachorism.

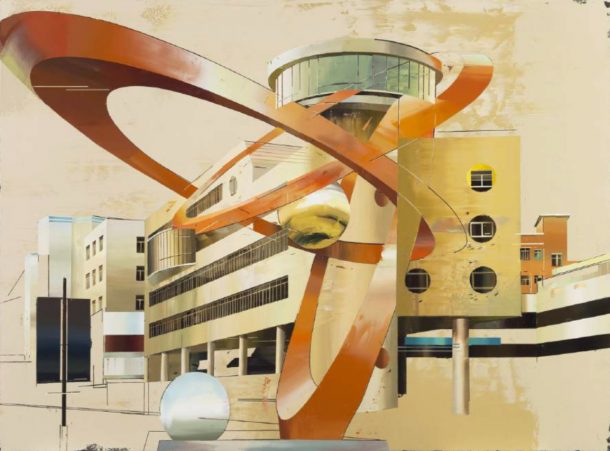

Oil on canvas, 150 × 110 cm

Oil on canvas,150 × 200 cm

The “autonomous epidermis” of the city refers to Cui Jie’s use of the angle of façade design as entry-point into a production of architecture devoid of depth perception. She fully unleashes the mediating significance of her compositions, and couples it back to painting itself. She relies on modes of expression involving the Deleuzian “generative diagram,” founded on the ideas of Peter Eisenman. By stacking together fragments of the cityscape such as streets, squares, basements and pedestrian overpasses, she demonstrates and makes plain the architectural process of an “incident unfolding.” The countless geometric surfaces and lines passing through her compositions cause a melding of the smooth and grainy forces at work in the picture. Previously, China has drawn on a plethora of prototypes for the basic realization of its modernization: German Bauhaus, Russian Constructivism, Stalinist architecture, the Japanese Metabolism school, the International Style spearheaded by Le Corbusier, etc. By culling eclectically from these influences, the artist condenses these prototypes into a “structure of feeling”2 that documents the evolution of spatial forms and the history of differentiation. More concretely, from 2013 to 2014, this “structure of feeling” emerged in her works as her envisaging of the symbiotic relationship between architecture and sculpture (in particular, public or municipally ordained sculptures). The sculptural qualities of architecture and the architectural qualities of sculpture are accentuated in one and the same canvas. In Building of Cranes and Pigeon’s House, birdlike shapes are depicted in pairs, encircling a typical residential building in a configuration hinting at the notion of habitat, a congealed and ardent sense of belonging, a remnant subconscious of the era of collectivism. The piece Worker Cultural Palace in Dongguan shows a public place once used to promote public life during that same era. Embedded in the image are a magnified, spherical celestial body and a circular orbit pattern, both of which owe their social educational importance to the fact that science and technology have always been symbolical of advanced productivity.

Oil on canvas, 150 × 200 cm

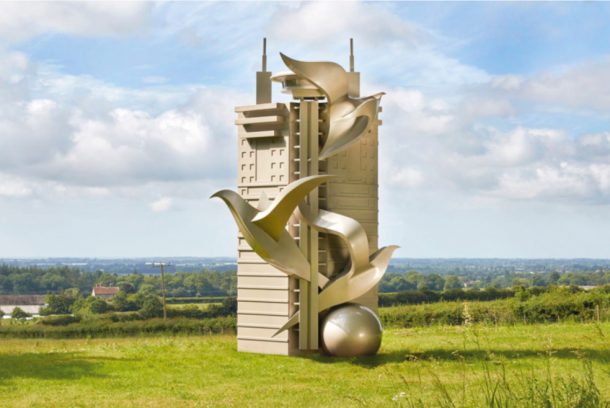

From 2015 to 2016, in preparation for a sculpture commissioned by CASS Sculpture Foundation, in an unprecedented feat, the artist agreed to the foundation’s wish of producing and 3D-printing a data model for one of her two-dimensional works juxtaposing sculpture and architecture. Unlike the final physical sculpture, which sported much larger dimensions, this scale model served as a research reference from which to glean more know-how on the sculpting process, while computation errors in the data conversion process provided wiggle-room for imagination. Cui Jie lays bare the state of distortion occurring within this back and forth transfer between sculpture and architecture. Continued stripping down of the image inspired her to create of a series of white sculptures, which helped add a sense of layering to the epidermis of this interplay between sculpture and architecture, i.e. the canvas itself.

Colored stainless steel and aluminum, 260 × 450 × 250 cm

View of “A Beautiful Disorder,” CASS Sculpture Foundation, UK, 2016

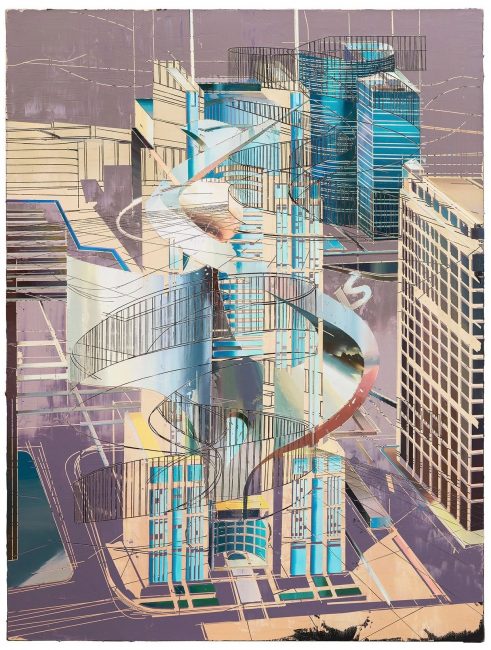

Meanwhile, Cui Jie expanded her paintings’ focal points to peripheral elements such as hotels, hospitals, airports, or infrastructure that played a pivotal role in China’s reform and opening-up policy, such as People’s Commune Dining Hall, a structure which grafts together the international window shapes typical of the country’s transitional period with the majestic and robust, populist forms of an earlier past. Rather than being geographically defined, the localities depicted in her works are essential nodes that act as vectors for globalized network flows, eventually leading Chinese cities towards a homogeneous, generic state. Seeing how external capital attraction lies at the root of urban construction and development, the commercial structures that go hand in hand with this influx of capital occupy the center of every major city, and dictate the everyday work routines of the ordinary middle class. In her work Shanghai Bank Tower—the title of which refers to a building erected under the guidance of the Kenzō Tange Associates—Cui Jie highlights the exterior wall decorations of this neutral looking financial office block and its surrounding buildings: glistening blue glass panes and a number of suspended spiraling staircases intersecting with S-shaped blocks. To a certain extent, the work pays tribute to the concept of “symbiosis” espoused by Japanese post-war architects. Biology-inspired tropes of this sort are a common sight in Cui Jie’s creations, as if to resist the mechanical principles and industrial processes of our modern age. Her works hypothesize on the ambivalence of either sublimating within reality or escaping it, while dynamically flowing lines are put to use as optimal tools for severing the suppressive constraints imposed on individuals—especially middle class ones—by cities’ existing regulations and rigid networks.

Oil on canvas, 160 × 110 cm

Deleuze formulated the following: “One is no more than a line, like an arrow crossing the void. […] One has become like everybody. […] One has entered becomings – animal, becomings – molecular, and finally becomings – imperceptible.”3 Cui Jie has, in effect, shown proof of her inherently revolutionary mentality with regards to precise control over formal language. By closely following those “lines of flight”4 referred to by Deleuze, and thus “becoming” along different pathways, she drives centralized social organization structures—which are represented through architecture—towards a point of criticality. Nomadic thoughts incited by lust assist her in moving back and forth between the individual and the collective subject, thus enabling her to find a connection with her environment and with others.

Acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 220 × 180 cm

Courtesy Antenna Space

In Cui Jie’s most recent work, this connection appears as a more downright humanistic inclination, as she shifts her observation to the conjugal relation between the human body and the singular artifice most accommodating to its dimensions: the chair. An across-the-board look at the history of architecture in the 20th century led Cui Jie to become more mindful of chairs created by architects who took on the role of designers throughout the modernist movement. Apt examples of this are the Red and Blue Chair designed by Gerrit Rietveld and Marcel Bruer’s Wassily Chair. These chairs were generally emblematic of their makers’ architectural styles, and were instrumental in molding style into taste by virtue of being embedded in all aspects of daily life, yet without necessarily being a perfect fit for the human body itself. Conversely, the now ubiquitous ergonomic chairs might well be feats of architectural subjects that truly override the individual. They don’t so much provide support for the average white-collar worker to work and perform their labor more efficiently, as endorse and help uphold the moral image of the middle class. The works showcased in Cui Jie’s 2018 solo exhibition “Maison Fueter” and the 2019 solo exhibition “To Make a Good Chair” all bore relation to this theme. Not only did the works in these shows conspire with the rooms of the exhibition venue itself, but Cui Jie’s perspective also began to drift in and out of architecture: this went beyond her displaying the bearing of a flaneur, but also related back to a consideration of the individual within the office environment furnished with ergonomic chairs, desks and half-open cubicles. Moreover, her addition of surface textures using sprayed-on specks and moiré patterns confers on the entire canvas an appearance of a glass curtain wall or digital screen, which interacts intertextually with the digital screen on the canvas facing an ergonomic chair, all of which echo the “screenification” of modern life. It is on this basis that Cui Jie attempts to capture the bustling and chaotic background noises of fractious cityscapes, as well as the coloring of three-dimensional architectural shapes by various systems of lighting. This temporal way of documenting the “economic outer shell” of our society, has helped bring to light the “formal essence” of a host of spatio-cultural issues. (Translated by Sid Gulink)

Acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 220 × 180 cm

Courtesy Antenna Space

1. Richard Poirier, “T.S. Eliot and the Literature of Waste,” The New Republic (May 20, 1967) p.21.

2. The notion “structure of feeling” was first put forward by Raymond Williams in the 1954 book he co-authored with documentary director Michael Orrom, titled Preface to Film. Later on, it was further expanded and developed in the book The Long Revolution (published in 1961) and the 1977 publication Marxism and Literature. This notion refers to an epitomized manifestation of meaning and value experienced by a generation of people in their daily lives. Having been repeatedly passed on and duplicated, this mode of thought clearly reflects the impact social and historical contexts have on individual experience, to the point of being inseparable from larger, complex relations of ethnicity and local culture that are being formed.

3. Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, pp. 199-200.

4. Gilles Deleuze with Claire Parnet, Dialogues, new edition. Paris: Flammarion, 1996. pp 49.