Enter player name:_ _ _ _

| March 23, 2022

1

Flying home has become difficult since covid and a mandatory quarantine were not escapable. For 28 days in a liminal phase, I must have been tamed by this enclosed space in which my daily activities were very monotoned. While lying in bed after the third meal of the day, I recalled a post-supper activity that I very much enjoyed during the lockdown in London: chess.

My flatmate, once a champion at a regional chess tournament in New Zealand, has been teaching me chess since 2020. I started revising his chess books and watching YouTube videos: about fundamental rules, jargon, chess etiquettes, calculations, strategies, case studies… Never have I thought chess would be part of my coping mechanism in this global turmoil; it was indeed one of a few entertainments that could distract me from my paranoia. It was perhaps a new “hobby” that made me less anxious? Or, it was the fun when we realised a formal connectedness that placed us at opposite sides of a square wooden board. The ritualistic nature of the game rejected all the ordinary conversations between us temporarily; no one was fussing with the dirty dishes or the unpaid bills.

Rules in chess are not complicated and players can leverage the rules to win. But fighting back to a draw is a completely different story; no one wants to lose when there is a chance to draw and no winning player wants to draw when there is a chance to win. One scenario of draw that can happen is called a stalemate in which the players are forced into a tie game and a draw is declared. There are different ways to a stalemate; for instance, when a player is not in check and cannot make a legal move, a stalemate occurs. The King is obviously under threat but the opponent cannot claim a win so the game ends there.

A draw means a win; at least for me, it is so. However, it is my mindset that has made my strategies full of flaws Upset at having failed at every single game – let alone the fact that I had no chance to a draw – I, however, didn’t quite blame myself; “he is graded”, I thought. An alternative option which was then encouraged by him was to download an online chess app.

So,

this is where I am now,

in bed,

playing chess with someone called user380124.

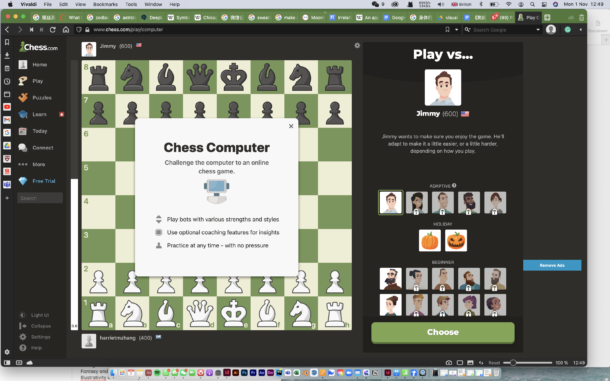

Interface of the online chess website chess.com

Image provided by the author

2

It has been roughly two years. I have changed from eyeing on multiple exhibition openings on ArtRabbit to easily getting tired of watching screengrabs of virtual artworks. I’m not sure if a “romantic boredom” really existed in my schedule because after all, my days spent in a tiny flat in South Kensington were not too intolerable. Or, you could say the actual boredom was romanticised as I was used to the very reality. It came to an end when we were liberated from the stupidity of a national lockdown that did not quite restrict people from going out. I could finally free myself from my laptop, my bed, and my kitchen, though temporarily. I could finally let go of my paranoia too.

I would probably still brag about how I was trained to cram multiple exhibitions and events into a rainy afternoon, cycling alone between destinations of art-seeing without a single word of complaint. Nor was I easily fatigued from meeting friends or mere superficial socialising. I would also be surprised that I have now agreed with terms like “online reality” or “offline reality” which, I thought, only existed in incarnations of scholarly assumptions. The parallel movements of both online-ly and offline-ly substantial realities are obscure but straightforward. However, I have discovered before too long that eyesore and fatigue from lockdown became my worst company at real exhibitions. Let alone the labour before arrivals, seeing became a new task. What’s worse? While my friends and I stared into the void on the notorious London tube which allowed no signal whatsoever, I heard my speaking, “how unreal and awkward it is to see real people! Aha!”

Dang it. Solitude sounded better.

3

I saw a joke on chess.com’s online forum the other day:

“Why don’t we go out and play some face-to-face chess?”

The hottest answer was, “it depends on the face.”

Jokes aside.

Initially, I thought switching to online chess would be weird because I was trained by anthropological writings to be cautious with switching to any online platforms and replacing my so-called “substantial reality” with “plastic reality”. I was then joked at by my flatmate as it wouldn’t make much of a difference due to my poor chess skills. Nevertheless, playing against someone in real life is not necessarily better – whether symbolically or actually more substantial – than online games. Heavy romanticisation over real-life chess games with a tangible chess pal can be a powerful, as well as condescending, opinion that promotes an “authentic” form of chess playing. But what is such authenticity anyways?

Indeed, in-person games might be more fun because of social interactions and atmosphere. The intensity of these games comes from eye contact, gestures, and each party’s unique way of communicating through the board. The very connection between players and the board locates in the movement of every chess piece. Regardless of skills, my chess pal and I interact differently with the chess set, with each other, with our decision-making egoistic selves. We value different pieces according to our own systems as we are familiar with different strategies – although I hardly had any so-called strategy. As time goes by, we both started to recognise the semiotic patterns in the other’s behaviours, which were independent of chess knowledge or skills.

Oftentimes I had to think over how to play next, while the movement of my eyes was tracked so he could easily tell what I was planning to do. For someone like him who could recite all the movements and play chess with me while he was lounging in sofa and coding, my strategies were never difficult for him to tackle. He would just shout out his next move (for instance, “pawn to F5”) and wait for me to think over and over. However good I thought my attempt was, he would then point out with an obvious attack on a side that I have absolutely neglected. As a result, the difference in pace became rather significant in our moves.

Pace difference in online games is very interesting. If I were to play with a human player, I would be extremely conscious of myself. I have never bothered myself with my slowness when I played with my flatmate, face-to-face. But the strong sense of being spectated in online games with real players was stupidly odd; although I would try to calm down, my ego seemed to be doubting, “will they remember my ID and tell the others how shit I played?” However, on the other hand, if I were to play with AI, I would take all the time I needed.

It might be a question of surveillance and perhaps also a question of proximity. The location/position of the person or machine against the chessboard was not defined. What’s worse, I have certainly dramatised the closeness between the player and myself. If they did not know me, why should I care about my pace, if not my failure?

4

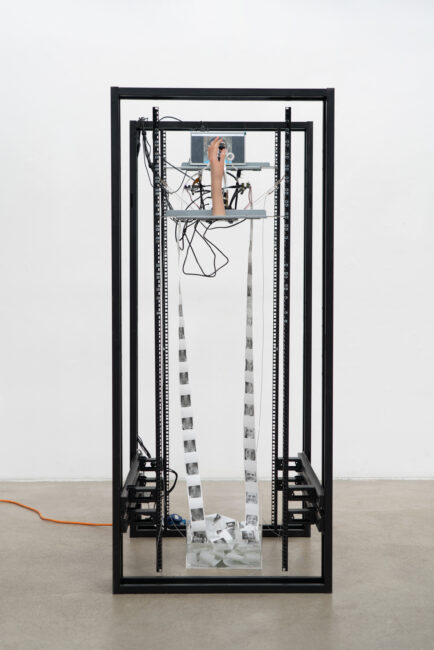

The last show I saw before my departure from London was at Cromwell Place. Zhihang Li’s installation stood in the middle of the showroom, alongside others’ from the RCA’s Photography graduate show – After the High Tide.

Waterfall, it was called. Hollowed server cabinet framed the whole structure with two cameras against each other. One faced a screen in which AI-generated portraits were refreshed every 15 seconds, symbolising the pace of automation in a highly artificial society. On the other side, I was met by a camera in a plastic dummy hand that represented a humanly gesture of “containing”.

While the cameras captured AI-generated faces and viewers’ real faces, they would signal the printers to print them out on two streams of thermal papers. Rolling down and forming a waterfall, the printed sides face each other; faces on the papers look into each other while watching the others fall into the alcohol tank and disappear.

“Who I am is who I am to other people; I exist in relation as someone seen and experienced by others.”

– Ozawa-de Silva, 2010; from Shared Death: Self, Sociality and Internet Group Suicide in Japan

The dual nature of being individual and interdependent is conveyed in the installation. It ended one’s autonomy as the installation juxtaposed one’s self with the AI-generated identity and automated the process into a passive, reciprocated, awkward, and face-to-face stalemate that existed long enough until they all disappeared one after another.

Zhihang Li, Waterfall, 2021, installation view, Cromwell Place, London

Courtesy the artist

5

A self is seen.

A self is seen by others.

A self that is seen by others comes through.

A self that is seen by others comes through the perceptions of theirs.

A self makes two things equal.

A self makes the self that’s seen and itself equal.

A self tries.

A self fails.

A self is in stalemate with itself.

6

Our infinite needs and fears for worldly life form a chain reaction and selfhood becomes the agent of these collisions. When the value of life and matter is at the centre of negotiation between selfhood and neighbourhood (here it entails a rival that’s nearby), has selfhood been seen? Wouldn’t it be the end of one’s autonomy to accept failures after rounds and rounds of maintenance?

A stalemate between Him (the Uppercase, patriarchal, masculine him) and me, between me and myself, between selfhood and otherhood…is not a result of tossing and turning, or of failed maintenance; but a contact zone for mitigation and relief. Therefore, it is not a question of whether it is a good match, but the proportion of proximity and pace which gives relationships the character of complexity. Stalemate entails an intolerability before a threshold is eventually met. For someone like me who does not believe in serendipity, stalemate gives me comfort, for it is a choice that reveals power. Ending its autonomy regardless, selfhood is moving on to the next game.

Harriet Min Zhang, born in Suzhou in 1997, often finds herself in between cultural imaginaries. She is an independent curator that prefers reading to writing.