Hong Kong outside the Mainstream Discourse: Fate and Chance Encounters in Johnnie To’s Films

| October 8, 2022

As one of the few Asian regions to enact the common law as its legal foundation, Hong Kong has long positioned finance capital as the foundation of its economy. It’s just as Marx has said: finance capital differs from industrial or commercial capital in that it is never associated with any specific commodity; instead, it is essentially credit-based and thus fictitious. Hong Kong, a region that is highly reliant on finance capital, has been playing the role of a virtual casino, where “money begets money,” not unlike the kind of capitalistic games/gambles discussed in Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s works. What kind of ideologies would emerge from such a society? Johnnie To’s Life Without Principle (2011) provides an answer: as all gambles are intertwined with chance and fate, Hong Kong has adopted an ideology that is prone to speculation. Films directed or produced by To often evoke the image of a gambler who “wagers against fate.” Yet, they do not subscribe to an opportunistic, cynical attitude; rather, they’re more about affirming the perspective that simply accepts “chance encounters as fate.” To quote a famous line from To’s The Longest Nite (1998): “You and I are like pinballs; where we go, when we stop… is not up to us.” Many events that occur in life elude human control, so we must understand the role that chance plays.

Tat-Chi Yau, The Longest Nite, 1998, 81 minutes

To some extent, To’s films do express a kind of cynicism, but it differs from Slavoj Žižek’s notion of an unconscious repression engendered by a refusal to perceive the real, and instead resembles the impersonal and “let nature takes it course” attitude of Stoicism (which originated from Ancient Greece’s Cynicism). In fact, director Wong Jing, the son of To’s mentor Wong Tim Lam, is keener on expressing the Žižekian brand of Cynicism, in narratives that transform even truths and untruths, good and evil, into commodities that can be bought and bought. Jonnie To’s films, on the other hand, address something that reaches deeper than perceptible phenomena—the tension between the aforementioned ideologies and certain preconceived beliefs. Perhaps such a tension is the true core of the “Hong Kong perspective”—it encompasses an alternative understanding of fate and acknowledgement of esoteric knowledge, and even praises of the spirit of Xia.

Responding to Hong Kong’s “Fate”

Johnnie To makes films that reflect an understanding of fate typical of Western tragedies. According to Aristotle’s theories of drama, the hero’s tragedy finds its roots in unforeseen “chance encounters” and an attraction to fate. It is not difficult to see that To’s narratives always feature some sort of extraordinary “chance encounters” and struggles against fate that usually lead to the protagonist’s downfall. Such a narrative parallels the curiosity toward/resistance to fate thematized in Western tragedies, one prime example being Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex. The protagonists encounter destiny-changing incidents because they’re driven by a compulsion to understand fate—the message in the tragedies’ endings being that viewers recognize the limits of rationality. In contrast, Jacques Lacan’s understanding of tragedies is more structural. Lacan believes that the essence of tragedy is a symbolic “big Other” that functions as a superego master who sets the game’s rules: the more the subject attempts to escape from or defy the “big Other’s” decree, the deeper they fall into its trap.

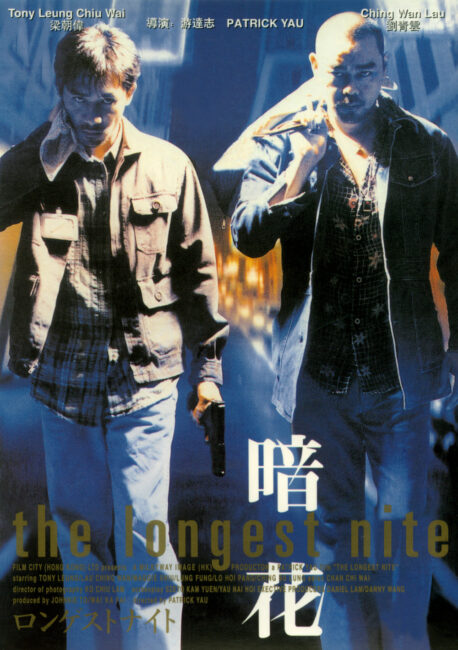

Poster (Hong Kong) of The Longest Nite, directed by Tat-Chi Yau, 1998

From Sam (played by Tony Leung) in The Longest Nite to Jack and Martin (played by Leon Lai and Ching-Wan Lau) in A Hero Never Dies (1998), To’s characters are often ensnared by those who dominate their reality, and they try to rely on their own strength to take back control of their destinies. Yet their misfortunes spring precisely from their desire to break the shackles of fate. In the opening act of A Hero Never Dies, the protagonist beats up a fortuneteller, while in The Longest Nite the headstrong protagonists unknowingly march into the gang bosses’ ploys. Both narratives foreground how fate exploits the characters’ overconfidence in their own agency, thus ensuring the tragedy that follows.

Does Hong Kong not resemble such a protagonist? In the context of the Cold War, the West intended to establish economic and ideological dominance in Asia through the financial center that was Hong Kong; and after the handover of Hong Kong, it was instrumentalized as a listing platform for many domestic state-owned and private enterprises. Hong Kong, from its skyscrapers to its slums, is always steered by geopolitical forces, and its cultural prosperity before the handover, too, was partially due to the inflow of international capital. In a sense, the “chance encounters” of To’s films are not some probabilistic occurrences or “accidents,” but are the consequences of the protagonists’ overreliance on reason and their disregard of impersonal factors. The films’ underlying logic of tragedy reflects the anxieties and self-doubts of a post-1997 Hong Kong—1998 marked the beginning of its economic decline after decades of growth. Prior to this juncture, Hongkongers used to believe that they could realize their ideal selves through their agency alone, but alas the emergence of a global financial crisis, much like a “big Other,” lured these confident subjects into the trap of a bursting housing bubble. The Hong Kong ideology encapsulated in these films shows a stubborn conviction for modes of production, namely finance and real estate. Just like the film protagonists, Hong Kong hoped to withstand looming tragedies by exercising its agency; unfortunately its defiance only attracted more of fate’s torments.

Johnnie To, A Hero Never Dies, 1998, 97 minutes

Johnnie To, A Hero Never Dies, 1998, 97 minutes

Remedies from an Eastern Perspective

In addition to depicting protagonists whose agency has constrained them, To’s later films began to attribute such limitations to an obsession with the “self.” Fellow filmmaker Wai Ka-Fai certainly informed his thinking on this subject. Wai is dedicated to Buddhist studies, which is apparent from the discussions on karma found among many of their collaborative works. In the film Running on Karma (2003), which they codirected, the male lead (played by Andy Lau), who has a gift for perceiving karmic movements, proposes a way to break the chains of cause and effect: to let go of all speculations on the relationship between tragedies and the “self.” As the female lead (played by Cecilia Cheung) attempts to make sense of her impending death from karma, she asks the male lead, Big, about the reason for her tragedy: “Do I have to pay my debts with my life because I was a murderous Japanese soldier in my previous life?” Big’s answer subverts the mainstream understanding of karma: “It’s not about your previous life, nor was Lee Fung-yee [the female lead’s name] a Japanese soldier. It’s just that Japanese soldiers killed people, and Lee happened to bear its consequences.” The film thus attributes tragedies to fixations on the “self” and suggests that the only way out of such karma is to abandon selfness and learn to perceive life without ego. Only then can one recognize that suffering does not come from tragedies, but from the natural and constant changes of the universe. These changes could not be more ordinary, and so-called tragedies are merely human-made narratives that reflect our desires toward all the earthly objects that reify the self, such as wealth, fame, and lust. This explains the ending of Triangle (2007, codirected by Johnnie To, Tsui Hark, and Ringo Lam), which proposes a method for letting go of the notion of the self: we must abandon our objects of desire in order to avoid tragedies. Although the protagonists of this film lost the treasure they were looking for, they managed to reach reconciliation with each other and themselves.

Johnnie To/Ka-Fai Wai, Running on Karma, 2003, 92 minutes

If Hong Kong society possesses some sort of subjectivity, then its indispensable object would certainly be a finance-oriented mode of production. This is to say, Hong Kong ideology covets the opportunities and prospects that arise from speculation and gambling. What Hong Kong overlooked during its prosperous years, however, are the impersonal changes in nature, and its obsession with a singular economic mode has also led to blindness toward other possibilities of growth. Regarding human tragedies, while To’s films address rather abstract philosophies of life, they also offer highly specific remedies to Hong Kong’s maladies: Hong Kong must learn to embrace chance encounters and let go of a preconceived “self-identity” (mode of production) to cure itself. Consider what South Korea did following the financial crisis: after more than 20 years of investment in its culture industry, it is reaping the bountiful rewards today. The Hong Kong government, in contrast, suppressed the local cultural imagination with its shortsighted standardizations and its outdated “civil servant mindset.”

Hark Tsui/Ringo Lam/Johnnie To, Triangle, 2003, 101 minutes

Hark Tsui/Ringo Lam/Johnnie To, Triangle, 2003, 101 minutes

Obscured Truths and Esoteric Knowledge

Beyond offering proposals for navigating the movements of fate and chance encounters, Johnnie To’s films also show a peculiar affinity toward obscured truths and esoteric knowledge that transcend rationality and logic. After all, rationality often limits our capacity to envision new possibilities, hence the protagonist’s (played by Sean Lau) line in Mad Detective (2007): “Don’t use your left hemisphere for detective work; instead, use your right hemisphere.” To’s films often foreground the intuitive functions of “the right hemisphere” through eccentric characters. Films like Mad Detective, Running Out of Time (1999), Running Out of Time 2 (2001), and Blind Detective (2013) express myriad ways of life—in particular, those of the mad and the “unproductive”—that are rejected by what Michel Foucault calls the modern episteme. Foucault contends that these states of being are exiled from modern societies because they convey truths that lie outside the architecture of reason. To, however, praises the esoteric, for tragedies, as I contended, are often born from humans’ overconfidence in a certain mode of thinking (or production). If only people could unearth their suppressed intuitions, then perhaps it would be possible for them to sidestep tragedies and comprehend the fickleness of life. Taking cues from the characters Szeto Bo (played by Louis Koo) from Throwdown (2004) and Chong See-tun (played by Andy Lau) from Blind Detective, one could conclude that sometimes it takes blindness to see truer things. This, in fact, echoes Foucault’s understanding of Oedipus Rex: he believes that Oedipus didn’t blind himself for redemption’s sake but so as to access a new way of seeing the world.

Johnnie To, Thrown Down, 2004, 95 minutes

Johnnie To, Thrown Down, 2004, 95 minutes

Johnnie To, Blind Detective, 2013, 129 minutes

Johnnie To, Blind Detective, 2013, 129 minutes

The films’ interest in the esoteric has a lot to do with the convergence of diverse cultures in Hong Kong. Although Hong Kong had grown into a leading financial center in Asia during the mid-1970s, and adopted qualification, commodification, and financialization as its new faiths, it also saw an influx of mystics and spiritualists due to the international dynamics of the Cold War. As a result, many traditional knowledge systems (e.g. astrology, traditional medicine, and witchcraft) are preserved here. If we attempt to understand such esoteric knowledge through the lens of Leibniz’s concept of “minute perceptions,” we wouldn’t regard it as superstitions or follies. These knowledge systems are excluded from so-called “means-end rationality” because they are already dormant in our minute perceptions and require alternative exercises for us to develop them—such practices resemble what Deleuze calls “becoming-imperceptible.” To’s films continually deliberate on the secrets of cultivating “minute perceptions” or “becoming-imperceptible,” and one of their aims is to answer fate: to reach new possibilities, we should break with the exclusivity of reason and assimilate subtle knowledge that could expand our horizons. Hong Kong became a steward of cultural heritage brought over by Chinese intellectuals from the South while also absorbing the cultures of ASEAN countries. Therefore, Hong Kong cinema features not only Taoism’s and Maoshan’s zombies but also Southeast Asia’s tales of witchcraft and Tame Head. Despite being a highly financialized city, Hong Kong doubles as a breeding ground for a multitude of cultures. This duality manifests in the fusions of symbols of finance and modernization (such as skyscrapers and sprawling streets) and “primitive” cultural elements, rendering the city a paragon for cyberpunk imagination.

Johnnie To, Running Out of Time, 1999, 93 minutes

Johnnie To, Running Out of Time, 1999, 93 minutes

A Spirit of Xia* that Transcends Kinship

Fated tragedies often originate from objects of obsession. From the vantage point of political economy, finance and real estate became a kind of opium as Hong Kong prospered. Hot money flooded Hong Kong’s real estate market, and when coupled with a high land price policy, Hong Kong’s housing prices and rents became the most expensive in the world, causing the cost of living to skyrocket. Hong Kong follows the English common law, though the New Territories retain some Qing dynasty laws, thereby allowing clan traditions and land ownership laws to be combined. Derek Yee’s film Overheard 3 (2014) addresses this phenomenon in a critical manner. Some scholars contend that although Johnnie To’s works frequently deliver critiques of finance capitalism’s greed, they also affirm the importance of kinship among the Jianghu (lit. rivers and lakes; the term originally referred to a dynamic underworld that eludes imperial control). What many scholars failed to consider were the differences between the spirit of Xia and the Confucian notion of (familial) “loyalty.” What To’s films embrace is not loyalty toward one’s own kin or clan but something akin to the “spirit of the wandering Xia” of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods—an ethos excluded from mainstream culture ever since the Qin dynasty unified China and codified the Legalist notion that “Xia obstructs laws.” Furthermore, To clearly took inspiration from Japanese Xia-themed films such as the works of Akira Kurosawa, which are certainly not the products of Confucian thought. In films like The Mission (1999), Exiled (2006), and Vengeance (2009), we see fierce struggles against wrongdoings and injustices in the Jianghu, as well as a sense of universal affection or solidarity. To take this argument further, I believe such a spirit of Xia opposes clan culture, as it completely does away with the latter’s obsession with the Lacanian “phallus” that symbolizes power. This logic is manifest in the two-part film Election (2005, 2006): the phallic “dragon-head baton,” which signifies the highest authority of the triad, causes the characters to slaughter each other, thus revealing that the famous line from the movie—“What would you choose? Your brothers or wealth?”—is a false proposition. Indeed, To’s films do not endorse loyalty prompted by kinship/clanship; rather, their ethos is closer in spirit to the Mohist school’s notion of “universal love.” This, in fact, conforms to Southern China’s “Hongmen” Jianghu culture, which was inherited by Hong Kong. The “Hongmen” moral codes promote the concept that “the Heaven and Earth are my parents,” encouraging people to transcend familial bonds to attain deep connections between lives unrelated by blood.

Johnnie To, The Mission, 1999, 84 minutes

Johnnie To, The Mission, 1999, 84 minutes

On the surface, it would seem that Hong Kong’s fate is entirely dictated by finance capitalism. Yet, through their peculiar perspectives, Johnnie To’s films attempt to reveal different aspects of Hong Kong, including the Eastern wisdom it has assimilated, esoteric knowledge that defies rationality, and its spirit of Xia. Undoubtedly, they are what Deleuze and Guattari would call “minorities.” These humble spirits, however, yield the potential to steer lives away from certain tragedies. In other words, to affirm these “minorities” is to accept the chance encounters in life. It is just as that famous line from Too Many Ways to Be No. 1 (1997) goes: “The choices that change peoples’ lives are not made for pivotal junctures and major events, but for things that hardly mattered.”

Johnnie To, Election, 2005, 100 minutes

Johnnie To, Election, 2005, 100 minutes

Nelson Zhang holds a Ph.D of Philosophy Department of Tsinghua University: Master of Philosophy, Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the translator of Zizek’s Violence, founder of Philosophy of Channel 01 (Hong Kong), He mainly researches upon psychoanalysis, Lacan, Deleuze, Marxism, etc.

Translated by: Kevin Wu

【1】Translator’s note: The spirit of Xia, or Xiayi, loosely translates to “chivalrous spirit,” but its ethos differs greatly from European knightly chivalry. The Xia are heroic swordsmen and vagabonds who abide by certain moral codes