YOUTH IN CHINA: IN LIFE AND ON SCREEN

| August 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 5

Whenever the topic of “art youth” comes up, many are eager to throw cold water on it. Some keep quiet, reflecting on the now seemingly unfounded optimism and heedless idealism of earlier generations, while others, reacting more to a current situation, fear that the young can only become pawns in someone else’s chess match. This latter group notes that “art youth” represent economic value in the eyes of the art system, and that it is precisely this system which decides which youth succeed and which fail, with the passive players too often succumbing to dismal gloom, while the active gradually lose their artistic autonomy, and often their innocence and spark in the process.

Both reactions are understandable; this is a question that requires us to go back to the source for an answer. When did youth become a panacea for all that ails the Chinese nation? The importance of youth as a category really only goes back to the waning days of the Qing. Just over a hundred years ago, as the fate of the nation took a sudden turn, the rise of youth was quite logical: if everything old and tired was to be changed, then of course the young could claim political correctness. From Liang Qichao’s famous essay “The Young China” to Cai Yuanpei and Xu Yuanjie’s debate on “National Vigor,” through Chen Duxiu’s “New Youth,” the political stock of Chinese youth seems to have risen constantly over the last century. Mao called youth “the morning sun,” telling them that “the world is yours.” They have the power to destroy everything, and all the influence that comes with that.

In a way, youth worship is a by-product of all that is wrong with the early radicalism of China’s modern era. Things went wrong quite early on, as Darwin and Huxley’s scientific theories, translated into Chinese, were used mainly to propagandize social Darwinism. This led to thinking like Lu Xun’s famous formulation that “I believe entirely in evolution, that the future will always win over the past, and the young over the old.” Like all of modern Chinese culture, Lu Xun loved youth. Only much later did he realize there was a problem with this worship, but the culture did not go along with him. Youth always believe they are right, which makes them more dangerous, as the Cultural Revolution proved. The political ascendance of youth came at a price, and could only give way to the “scars” and yearnings of the 1980s, and a new wave of rebellion after that.

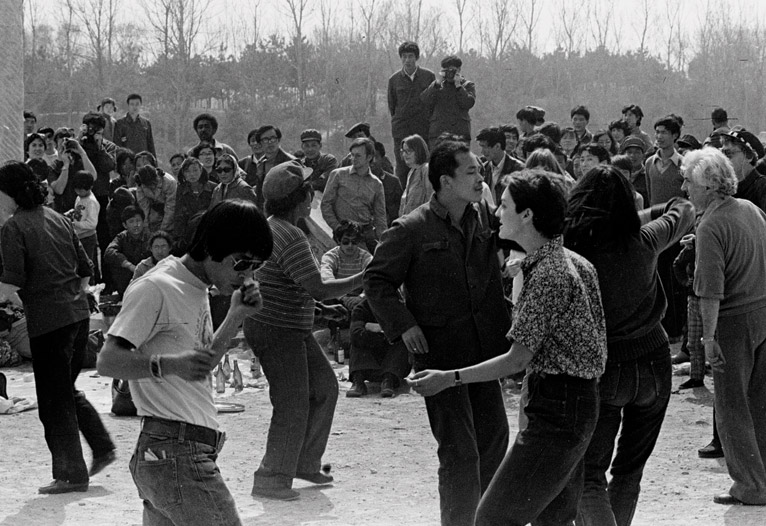

In art and culture, the predicament of youth is better than in society at large, because of art’s claim to being “non-mainstream,” a psychology that is difficult to shake. Generation after generation of art youth have done cultural work by just hanging out and being young. Back in the day, they formed painting societies, film societies, drama societies; today they populate groups on Douban or make indie exhibitions, photos, and magazines. The broader social circumstances don’t necessarily always support a youthful urge to form groups of their own, and the activities of youth collectives are often fleeting—as is the very designation of “youth” itself. But the latent power of this period is explosive, and regardless of whether it sustains itself for an extended period, its effects radiate through the broader culture.

These days, perhaps for the first time ever, the concept of youth in China does not exist as a political slogan, but as a naturally occurring cultural formation. The current youth culture was born of consumerism and the Internet, and today’s art youth are not immune from these influences. At this point, it seems relevant to look back at Chinese youth real and imagined (Qiu Jin, Nie Er, Lin Daojing, Yang Qiangyun, Cui Jian), if only to understand one intractable question: where we come from, and where we are going.