FRESH INK: TEN TAKES ON CHINESE TRADITION

| February 22, 2011 | Post In LEAP 7

As curator of one of the world’s premier collections of classical Chinese art outside of China, Hao Sheng’s responsibility is to explain a visual culture that, more often than not, alienates its viewers. Sheng recently invited ten artists to make contemporary responses to works from the permanent collection of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. In their most successful moments, the new works—as products of sustained observation and sincere emulation—demonstrate ways of relating to classical Chinese art that commonplace museum labels cannot possibly achieve. Furthermore, they show the spectrum of responses contemporary Chinese artists are making in the face of pressures to relate to such a history.

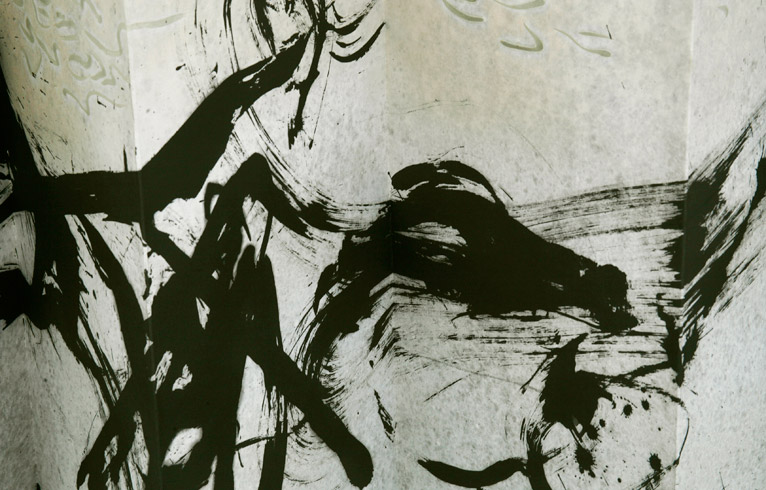

Among the most revealing of these dialogues between past and present is Arnold Chang’s reaction to Jackson Pollock’s Number 10 (1949). Chang’s Secluded Valley in the Cold Mountains relates to Pollock’s brushwork in a way that educates viewers anew on both Chinese painting and Abstract Expressionism. The viewer is meant to view both paintings not as images but as actions with which the eye and mind can sympathize bodily. By calling attention to how abstract expressionists like Pollock found the power of their gestures in the calligraphic marks of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, and by insisting that Pollock’s work lay flat on its back, positioned face up so the viewer stands in the position of the artist, Chang teaches contemporary viewers that viewing literati ink painting is dependant on the same active sympathetic re-enactment as viewing the more familiar actions of Pollock’s painting.

The other artists in the exhibition who paint ink landscapes, notably Li Huayi, Liu Dan, Zeng Xiaojun and Qiu Ting, practice a kind of painting that is often seen as similar to Chang’s simply because the subject of landscape and the medium of ink and paper are bound to ideas about Chinese tradition. But their brushwork is often based on very different sources, including photographs, monumental Song dynasty landscapes, and a style of layering diffused washes influenced by Western watercolor. The show’s strength is that only a minority of the artists demonstrate an interest in Chinese tradition that is in continuum with tenets of literati painting. The variety of responses in these “ten takes on Chinese tradition” ranges from passive acceptance to indirect interrogation and exposes the challenges that face contemporary Chinese artists charged with the implicit imperative of the past.

While their presence in “Fresh Ink” might seem strange, the work of figural painters Yu Hong and Liu Xiaodong are as subtle and engaging as those of painters more commonly labeled ink artists. Figurative painters interpreted their responsibilities towards the objects of the past very differently than the landscapists, responding to their chosen paintings by emulating the social dynamics of the original works, not the techniques or compositions. Liu chose Erlang and His Soldiers Driving Out Animal Spirits, a violent, animistic, and colorful Ming handscroll illustrating a famous parable; his work, What to Drive Out?, painted in acrylic and charcoal on paper, shows a group portrait of Boston teenagers standing on a blank white ground as they look to the left where they have written their own poetic musings on violence directly on the paper. Chinese tradition in the hands of Liu and his subjects thus becomes less about style than ideas of social responsibility that transcend specific historical circumstances.

Liu Dan, on the other hand, paints with the same materials of literati painting, and takes a scholar’s rock—that classic literati object— as his subject. Yet his brushwork differs from calligraphic brushwork associated with literati painting, which he demonstrates explicitly in his installation Ten Differentiated Views of the Honorable Old Man. Each of nine vertical portraits of his seventeenth-century subject, a lithe and imposing scholar’s rock, is done from life-sized photographs. His short, staccato brushstrokes describe shifts in light over the surface of the object in a style that is overt about its photographic source. Liu’s tenth painting is a long horizontal landscape, a re-imagining of the surfaces discovered in the nine photographically sourced studies. In the transition from literal depictions of natural surfaces to a single digested landscape, Liu emphasizes another principle of classical Chinese painting: learn from natural forms but do not copy them. But he is frank about his disinterest in being boxed in by literati historical referencing. In response to a question about what differentiated his work from Wu Bin’s famous sixteenth-century painting Nine Views of a Rock, Liu’s response was: “Whether [it is] contemporary or Ming [dynasty] is not my concern.” Other outstanding responses include Li Jin’s seven works, all titled Reminiscence to Antiquity, in reaction to Northern Qi Scholars Collating Classic Texts (11th century), with bacchanal mutations in a technicolor array of “boneless” (without ink line) washes, and Qiu Ting’s Visit to the Eight Great Sites, a landscape handscroll painted in transitions of ink wash that shift between mist and form in even more subtle ways than its canonical model, Zhao Lingran’s Whiling Away the Summer by a Lakeside Retreat (dated 1100).

At the accompanying symposium, each of the artists spoke about working with the MFA collection in glowing terms, as a privilege. All chose to work with Chinese art, with the exception of Chang, inadvertently pointing to the often self-imposed pressure by contemporary Chinese artists to perform their Chinese identity in an international setting. This mirrors another paradox: while the rise in interest towards defining Chinese tradition comes from sources both internal and external, the power to define narratives of Chinese tradition is often found in museum collections outside of China, which benefited from the nineteenth- and twentiethcentury turmoil that initially unseated the power of Chinese tradition. Surprisingly, given the repatriation campaigns for classical art occurring globally, none of the artists of “Fresh Ink” took on this elephant in the room.

No other contemporary art is quite as bound to its own past and national origins as ink painting, so often preceded by the words “traditional” and “Chinese.” By asking Chinese artists to reflect on traditional China, and by titling the show “Fresh Ink,” this exhibition treads a fine line between imposing the century-old burden of reconciling tradition and modernity and allowing artists to react to it. And yet to its credit, “Fresh Ink” is remarkably handsoff. It does not try to explain contemporary ink painting, nor does it present a single explanation for the paintings of the past. Its simple premise is that contemporary art benefits from sustained observation and sincere admiration of past art, an idea which may fly in the face of both modernist doctrine and postmodern irony, but one that results here in several successful contemporary works. Michael Hatch