YANG FUDONG

| May 23, 2011 | Post In LEAP 8

Yang Fudong’s recent outing at Marian Goodman’s Paris outpost showcases two works: the multichannel video installation Fifth Night and the photographic series “International Hotel,” both of which were debuted in Shanghart Gallery’s “Useful Life” exhibition last year. But while “Useful Life” (named after an exhibition by Yang, Xu Zhen, and Yang Zhenzhong in 2000) looked at three tight-knit artists and the changes their respective practices had undergone in the previous decade, this exhibition is about Yang Fudong as an individual practitioner.

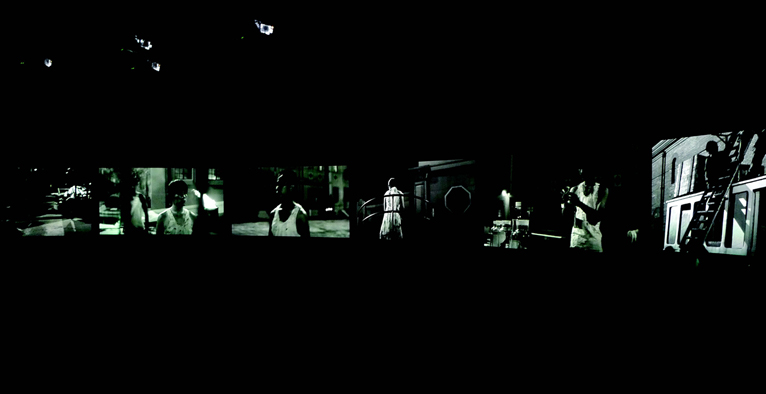

Fifth Night is a seven-screen video installation, with each screen running 10 min. 37 sec., the length of a reel of film. We once again see the same itinerant youths who always occupy his films, with their pensive, pent-up expressions. Each screen features one solitary “absolute” protagonist; together they compose a series of distinct and mutually unbeknownst worlds—a middle-aged man sitting quietly on a sofa, a girl strolling and gazing off in every direction, a young man hurriedly getting on and off a trolley car, workers smelting metal. Here Yang expands beyond his typical cast of fewer than ten, adding background actors; one screen’s lead character, in turn, becomes another’s extra. Moving vehicles proliferate: bicycles, rickshaws, and sedans pass through, adding a dynamic element to otherwise still shots, and expanding the space of the screen. The sets and props are Yang’s most elaborate to date, with stages, spiral staircases, and alleyways merging into one. The enclosed courtyard in which the piece was shot comes to resemble a maze, pushing the concept of the narrative spatial possibilities of cinema. This bold experiment, which takes an open, outdoor space as an interior, breaks down a boundary that runs throughout Yang’s other films, which have been shot entirely inside or entirely outside.

- Fifth Night, 2010, Video, 10 min. 37 sec.

People are well-acquainted with Yang Fudong’s years of research into the aesthetics of video and film, but Yang’s true concern has always extended beyond cinematography, in the experimental possibilities of recorded stock itself. Yang is perhaps unhealthily fascinated with disrupting his own cinematic language, not merely on the level of aesthetics, but of technique and concept. His 2009 work Dawn Mist Separation Faith was a movie in nine parts, and on nine screens, each of which consisted of a sequence of “no good” outtakes of the same scene. In Fifth Night, Yang instead shoots in a single temporality but from multiple vantage points. Seven cameras are positioned at different points on this compact set, resulting in a certain intertextuality among the resulting seven screens—not to mention a deeply layered narrative texture and, at times, a bit of plot confusion. In this way, Fifth Night helps us to understand the experimental arc begun in his earlier film installations.

In fact, an alternative fifty-minute edition of Fifth Night was shown in last year’s Shanghai Biennale, which includes four full takes as well as an earlier rehearsal. (The theme of the biennial was “Rehearsal.”) This version ends in “failure,” as one of the cameras breaks, leaving only six channels, and effectively interpreting the curators’ notion that “film is both a medium and a site, and the filmed work is both inside and outside of rehearsal.” In this instance, Yang transcended his traditional working process of shooting-editing-screening, and pushed further the theory he established in Dawn Mist that “anything which has been filmed can be shown.”

In the photographic series “International Hotel,” Yang Fudong seems to explore the photograph as film, or rather, the filmic possibilities of the photographic frame. He attempts to make photographs just as he makes films, using them to reveal tiny, invisible stories. This filmic nature endows the images with a beauty, and a power to move their viewers, far beyond their actual aesthetic qualities. Luluc Huang