LI YUAN-CHIA: HOW FAR TO COME HOME?

| June 8, 2011 | Post In LEAP 8

Artist Li Yuan-chia (1929-1994) spoke little but saw far. Unknown in his native China and largely forgotten in his adoptive Taiwan, his journey took him to Italy and later to England where he worked tirelessly for over three decades. A little understood and remarkably subtle artistic innovator, he worked first to incorporate Eastern philosophy into Western abstraction, and later created LYC, a free-form community of creators in the English countryside that anticipated artistic trends of participation and collaboration still decades away. Here, Simon Kirby looks at Li Yuan-chia’s journey, and contemplates his complex legacy.

SÃO PAOLO

In 1957, a group of young Chinese artists from the Tung Fang Painting Group, of which Li Yuan-chia was a founding member, exhibited their work in the Third São Paulo Biennial. This was perhaps the first time that international audiences were to see how artists from China were responding to the language of abstraction in painting. The exhibition was the first to be held in the daringly curvilinear halls of Oscar Niemeyer’s now iconic Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion in Ibirapuera Park, the whitewashed concrete structure that still houses the Biennial. Brazil was entering a period of fast economic growth, and despite an increasingly repressive military dictatorship, the country was at the forefront of a new kind of optimistic, international modernity— a modernity that was being experienced in many other newly decolonized and fast-developing nations around the world. The Biennial was an opportunity for Brazil to place its thriving art community directly within reach of the international currents of contemporary culture. It also provided a platform for distinctive avant-garde artistic voices from outside the hegemony of Western Europe and North America to be heard. The Tung Fang (literally, “Oriental”) paintings were shown alongside new Brazilian work, significant groups of Surrealist works, paintings by Jackson Pollock, and a collection of gentle English abstractions by Ben Nicholson, provided characteristically by the British Council.

GUANGXI-NANJING-TAIPEI

The story of how these young painters came to work together is part of both the great drama of China’s twentieth-century history and Li Yuan-chia’s singularly inspiring, albeit sad, personal story. Born in 1929 among the karst mountains of Guangxi Province, Li came from a poor family. A gifted child, he won a scholarship to a boarding school some distance away from home at the age of eight. He left reluctantly and, as it turned out, never returned. Three years later, with hopes of getting access to offer a better education, Li was adopted by a maternal uncle who served in the Republican army. These hopes were dashed a few years later when Li’s uncle was killed in the War of Resistance Against Japan, leaving the teenager’s subsequent education, absent of family support, to an ad-hoc and apparently comfortless series of institutions for bereaved children of military families. During the chaos of the war years, Li, along with his classmates and teachers, became part of the largely undocumented refugee crisis of the Japanese war. They endured a yearlong trek by foot across Guangxi, escaping their bombed-out school, then moving from place to place to escape the constant danger to their lives.

Arriving in Taiwan in 1949 as a war orphan refugee, Li Yuan-chia was already twenty years old. He was soon enrolled in Taipei’s Normal University where he received bed and board, a uniform, and a three-year diploma with a contractual three-year teaching post in an assigned school. University training was rigid and was administered against a political background of strictly authoritarian military rule. Remarkably, a group of young artists actively searching for ways to communicate with, and innovate in, emerging languages of contemporary art that they were learning under the private tutelage of artist-educator Li Chung-sheng (1912-1984). Li Chung-sheng must have been a remarkable person, as he inspired in his students a lifelong devotion and admiration. He kept his tuition fees low and maintained a strong sense of the creative potential of each of his protégés, which he nurtured in a way that was completely lacking in their formal college educations. British-Chinese scholar Diana Yeh, who interviewed many of the Tung Fang artists, notes how her subjects shared a sense that “to become an artist in this period of the 1950s in Taiwan offered a source of “personal liberation” and “salvation” from the intense sense of loss of home and family that they had all experienced through the war years.” It is the sort of personal reflection that Li Yuan-chia himself is unlikely to have offered.

Despite political and social upheaval, Taiwan in the 1950s offered an environment for artistic experimentation that continued upon what had been taking place previously in Republican China. The Fifth Moon Painting Group, for instance, which remained an important influence in the Taiwan art scene over the following decades, had drawn together artists seeking to reinvigorate Chinese traditional painting with the expressive abstract vocabularies then being developed in Western painting. The Tung Fung group, on the other hand, were avowedly international, embracing new avant-garde forms and exploring them from their personal perspectives as young Chinese artists who had survived tumultuous events.

Meanwhile, in the Western world, experimental artists and thinkers were famously discovering Taoist and Buddhist philosophies, becoming fascinated with the spontaneous and abstracted expressiveness of Chinese ink painting and calligraphy and the creative possibilities they seemed to offer. Naturally, Li Yuan-chia and the Tung Fang members had direct personal access to these cultural traditions, and quickly found that they could draw freely on them in their own experimental work. It is really from this point of convergence between Eastern and Western experience that much of Li’s work developed: a fearless contemporaniety which allowed him to embrace new forms, combined with a personal and philosophical universality that sometimes appears to have been his own undoing.

Throughout the mid- to late-1950s, Li Yuan-chia refined his abstract Taoist inspired painting as he evolved gradually towards his lifelong pivotal idea of the “Cosmic Point,” a minimal and at first gestural calligraphic mark that implied for Li, within its very restrained confines, a vast (Chinese) cosmology. “In 1959, my first [Cosmic Point] painting was a tiny black dot on a white square of canvas,” he later wrote. “Nothing could be simpler than that.”

BOLOGNA

One of the key activists of the Tung Fung group was the Shanghai-born patrician Hsiao Chin (b. 1935). Hsiao, whose father was the composer and Shanghai Conservatory founder Hsiao Yu-Mei, came from a background that could not have been more dissimilar to Li’s. Nevertheless, Hsiao’s energy and ambition were to have a decisive impact on Li’s own artistic future. In 1956, Hsiao received a bursary to study in Spain, where he spent a few years before settling permanently in Italy. Hsiao reported regularly to Tung Fang members in Taiwan on contemporary art movements taking shape in Western Europe. He also visited important exhibitions and was energetic in linking with influential artists and exhibition organizers. In 1961, Hsiao Chin alongside Italian, Japanese, and other artists active in northern Italy, established a new international artists’ group called Il Punto (The Point). Against a background of the European Informel, the Il Punto artists declared an aim to imbue a deeper level of spiritual experience into the work of new creation. As a manifesto, it resonated with the Chinese artists’ concern to infuse their work with philosophical meaning and value. Hsiao invited Tung Fang artists to join Il Punto, and in late 1962 or early 1963 Li Yuan-chia travelled to Italy to take part. He subsequently spent four productive years in Italy, living partly under the patronage of the flamboyant furniture manufacturer and art collector Dino Gavina, whose estate still holds an important collection of Li Yuan-chia works from this period. During his Italian years Li developed his idea of the “Cosmic Point” even further, producing painted works in which the point was appliquéd, punctured or painted onto the surface of the canvas. This device also started to assume a conceptual character when it appeared on painted wooden reliefs in which it hovers in the geometric wooden planes. British curator and critic Guy Brett takes up the story:

“The painted folding books Li made out of paper and cloth in the early 1960s are exquisite works. Indeed they are an astonishing production, ranging from ‘scrolls’ around twenty feet long when unfolded, down to small albums the size of a train ticket. The brushed Points have already their conceptual identity but are still calligraphic and delicately nuanced. Slight variations from page to page emphasize both constancy and change.”

During this period Li Yuan-chia was increasingly coming to the attention of galleries and of collectors. He mounted solo gallery shows in Florence and Milan and was included in group exhibitions in New York, Rotterdam and, importantly for the next step in his story, London.

LONDON

London in the early 1960s was entering one of its now legendary periods of creativity in the visual arts. Indeed, the city’s then bohemian West End was, for a few important years, at the center of this alternative international art world. Much of this owed to Signals Gallery, set up by Paul Keeler with the irrepressible Pilipino artist-activist David Medalla and the participation of Guy Brett. Signals worked with some of the most important emerging artists of the day. The gallery, set across two floors of a spacious London town house, often commissioned large-scale works. Medalla invited Li Yuan-chia to show there in 1965 and in 1966. For the second show, Li travelled to London to construct a large symmetrical geometric wall relief, now lost, that featured his signature “Cosmic Points.” Arriving in London Li found himself energized by the city’s atmosphere of artistic experimentation and, in a life that seems to have been characterized by abrupt change, he decided after the closure of the show not to return to Italy. He remained in England for the rest of his life.

Having already readily internalized the abstraction he developed in Italy into his own kind of metaphysical cosmology, Li Yuan-chia launched himself in new directions. His “Cosmic Points” evolved further away from their original calligraphic origins and his symbolic cosmologies detached themselves from their multi-media relief panels to become independent, disk objects of varying sizes: wall mounted, suspended as flying objects in space or as magnet-backed components that could be rearranged by the spectator across colored plates. He included text and concrete poetry, which he wrote in English, and invited viewer participation. He circulated inexpensive multiples to allow more people to own his works and later embraced the ideas not only of installation, but more radically of artworks as complete environments. Li also started to work with photography— a strand of work that became more important to him later.

CUMBRIA

The newly opened Lisson Gallery was actively showcasing the new Minimalism and Conceptualism of the London scene and Li Yuan-chia mounted two important solo exhibitions there, “Cosmic Point” (1967) and “Cosmic Multiples” (1968). Yet as with his years in Italy, just as Li was beginning to attract the attention of serious galleries and collectors, he once again turned in an opposite direction in favor of a new and radical decade-long experiment, the full implications of which remain subtle and somehow elusive to this day.

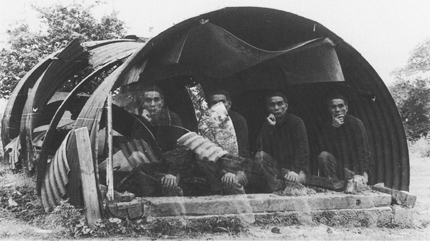

In the early 1970s, Li Yuan-chia felt a desire to leave London. He had already spent some time in the northern region of Cumbria on the invitation of his poet friend Nick Sawyer. He was enraptured by the dramatic scenery and in 1972 he bought a rundown farmhouse near the town of Banks from the much loved English colorist Winifred Nicholson who lived nearby (Winifred’s first husband, painter Ben Nicholson, is the painter who showed alongside Li at São Paulo). The house sits in an exposed and very beautiful landscape beside the ruins of Hadrian’s Wall, a second-century Roman fortification that some maintain was inspired by the Great Wall of China’s Han dynasty. Li moved into his house, erected a sign saying “Li Yuan-chia Museum and Art Gallery (LYC)” and embarked on a remarkable creative process in which he effectively merged his own individual identity as an artist with the hundreds of other artists, children, country walkers, and local country residents whom he freely invited to work, reside, and exhibit there. Almost singlehandedly and with very limited means Li repaired the buildings. He made gallery spaces by knocking down walls, constructed outbuildings, collected a library, and created a garden. He installed a hand-operated printing press and set about individually typesetting and hand-binding small square-format catalogues, one for each of the 330 artists or groups who presented exhibitions at LYC. Li reported that at its height LYC attracted a remarkable 30,000 visitors a year to this remote rural setting.

Li Yuan-chia himself remarked simply “I work like an ox.” Scholar Diana Yeh has connected this humble, pastoral diligence to Li’s Guangxi roots— seeing similarities between Cumbria and Li’s native Xu village near Lushan that begin with the physical beauty of the landscape. Yeh writes:

“Daily life in Xu village is harsh but the people that I met there were warm and welcoming. They are engaged in a constant process of extraordinary improvisation to maintain their homes, clothe themselves, bring up their children and grow their food. I felt that this is exactly what Li had been doing at Bank. Driven doubtless by sheer necessity it was nevertheless creative and impressive for all that. Li displayed exactly the same kind of dogged resourcefulness that I found in Guangxi and it made a lasting impression on me.”

Li Yuan-chia became fully absorbed with the tasks of creating the museum and gallery and subsequently made less and less work under his own name. Consequently, art historians looking for new works by Li from this period are disappointed. Yet this was at the very heart of Li’s radical experiment. The artist had melded his own individual identity with everything around him, and the entire marginalizing project became his artistic program, whether it was working with another artist to realize joint works, cultivating the garden, setting up an exhibition, staging a concert, maintaining the improvised buildings against the appallingly wet and wild weather, or publishing yet another catalogue in which he himself was curiously absent. Paradoxically, the person of the artist Li Yuan-chia became subsumed in LYC, an institution of his own creation and which bore his own name.

By 1982, the wider arts community in Britain was becoming familiar with what had until recently been radical notions of art practice— non-hierarchical open participation in the creative process, the dismantling of the boundary between “artist” and “non-artist,” land art, the creation of transient rural art interventions, and so on. Li Yuan-chia himself however was by this time physically exhausted after his ten-year immersion in these challenging and perhaps utopian ideas. Li longed finally to do something different, to go on holiday, to sell his house and to move on.

At this point in his life, however, a number of regrettable circumstances conspired against him. Naively, Li Yuan-chia allowed some temporary lodgers to install themselves in part of the LYC buildings. These lodgers later refused to leave, becoming increasingly troublesome and vexatious to Li. The presence of his unwelcome tenants naturally made the house almost impossible to sell. At this time Li also discovered the facts of his true maternity and was informed that his birth mother was ailing in poverty back in Guangxi. Li, who had been comprehensively denied a family of his own, hoped to make his mother more comfortable at this late stage in her life. He even hoped to return for the first time to China to visit her. Sadly, he was in a position to do neither.

With the closure of LYC and an increasing sense of personal isolation, Li turned back to photography and produced scores of haunting hand-colored works often depicting himself, draped in covers, in garden settings. He continued with his “Cosmic Point” works, including staged natural compositions and multiple-exposure photographic prints. Performance artist Cai Yuan, who has himself lived for more than twenty years in England, reflected on his discovery of Li Yuan-chia as a remarkable revelation: “A number of things during my first few years in England gave me a great jolt. The first was start when I travelled with my wife’s family to London to take part in a huge anti-nuclear pubic demonstration. We all took to the streets and chanted ‘Maggie, Maggie, Maggie, OUT OUT OUT!’ I remember wearing a dark green PLA overcoat and Chinese military hat complete with insignia. It was very exhilarating to me. Later, I made another, similar discovery. London’s Hayward Gallery opened a large-scale exhibition ‘The Other Story’ that showed the work of Afro-Asian artists in Britain. I suddenly came across the work of a Chinese artist active in Britain of whom I had remained unaware. Li Yuan-chia is an artist that I continue to respect to this day.” This was the last exhibition that Li Yuan-chia was to take part in. He died in Carlisle some years later.

Visiting Banks in 2009, I peered through cobweb-covered windows of the Li Yuan-chia Museum and Art Gallery. The building appeared heavy and damp and the garden was overgrown. Later that afternoon I visited Shirley and Donald Wilkinson, Li’s neighbors, fellow artists and long time friends. Here was a quintessentially English scene: a simple stone house whose windows look across a wet green landscape, a perfectly arranged print studio with tools and paper hanging from old wooden rafters, a woolen blanket on a comfy arm chair and a generous pot of tea and cakes. Invited to handle one of Li’s inscribed calligraphic, painted wooden blocks, clearly among the couple’s most treasured possessions, I felt how far one might have to go in order finally to come home.

Across the world in Xu Village, Guangxi, the school building that Li Yuan-chia paid for also now stands empty and unused.