XIE NANXING: STEPFATHER HAS AN IDEA

| August 1, 2010 | Post In LEAP 4

The exhibition “Stepfather Has an Idea!” features six paintings completed by Xie Nanxing since 2009, divided into two series that communicate in apparently dissimilar languages. The works in the “Untitled” series are nonfigurative in nature, employing implied and imaginary systems of words and symbols to transmit to the viewer, for example, a sexual re-interpretation and imagination of the original characters from the children’s fairytale Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. The figurative realist paintings of the “We” series are black and white reproductions of three erotically charged, titillating works from the 1940s by French painter Francis Picabia that originally comprised of “sexy” bodily sentiments drawn from woman’s daily life.

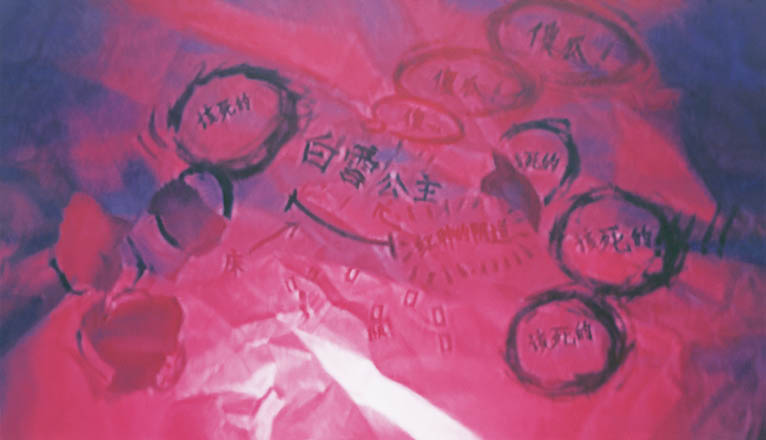

The three paintings in the “Untitled” series rely on a fusion of written language and graphic symbols, transmitting to the viewer a vague and ambiguous system of sexual meaning through words and symbols. Alone, the phrases inscribed on the paintings, “pay attention to the gesture of the hands,” “testicle,” “passivity,” and “stepdaughter’s second adventure,” all carry implicit references to the relationship between the female Snow White and the male Seven Dwarves. Meanwhile, the compositional features of the canvases themselves provide a systematic framework for idea generation. Take, for example, the words “red and swollen vagina,” which accompany a Snow White surrounded on all sides by the Seven Dwarves. There is no avoiding the associations of gang rape or incest that flash through our minds. Rapid image association like this shares as much in common with pornographic pin-ups as with the most-clicked online news headlines. As for the sexual association, the viewer experiences a departure from his or her memories of the fairytale’s original, pure and innocent Snow White, and ends up daydreaming about sexual revelry between a Snow White of the opposite sex and the Seven Dwarves, and, eventually, about cases of sexual perversion read about in the media (that is, from an imagined social reality). In this kind of image association, a certain “pleasure of thought” guided by symbols and imagery can be perceived, where experience is a precondition necessary for this kind of image association to happen in the first place.

The reproductions of Picabia’s erotic nudes burrow into the annals of art history to investigate the specific image characteristics of sensory association, or in other words, into the visual grammar conveyed by concepts. Thematically, the three original works by Picabia were rooted in the popular pin-ups and postcards of the time. By signing his own paintings with the Chinese transliteration of Picabia’s name, Xie Nanxing reiterates his emphasis on the meaning of the original works, and seeks out the true grammatical structure responsible for the dissemination of those images among the public. For both the “Untitled” and “We” series possess meanings and characteristics generally present in the dissemination of “sleazy” popular culture. Each uses different methods (one uses written language, and the other, specific images), but both intend for the viewer to complete the conceptual circulation of perception.

The grammatical exercises Xie Nanxing carries out in the realm of painting are a total departure from the early methods he used to express social themes. He now probes, from the very insides of art, the effectiveness of certain mechanisms as artistic language. For example, sex: through this sensitive point, he uses experience as the foundation for an imaginary space, and then within the exhibition space, uses abstract conceptual grammar to experiment with the temporary idea generation systems that have actually been lurking in the viewer’s public space for a long time already. Li Xiaonan