These “Recipes for Resilience” were compiled in the spring of 2022 in Shanghai. During the days (months, in fact) when food supplies were destabilized due to the strict lockdown measures in the city, to prepare daily meals according to rigorous or authentic recipes became nearly impossible and irrelevant.

Popular memes on social media showed weeds growing wild in the city’s poshest areas, and residents foraging for edible weeds on their neighbor- hood lawn. The joke is sour, however, if one digs into the actual motives and history of humans eating grass in dire times. Food scarcity is never so remote from us. Tragedies from the not-so-distant past and the current geopolitical turmoil in the world all point to the looming crises on way.

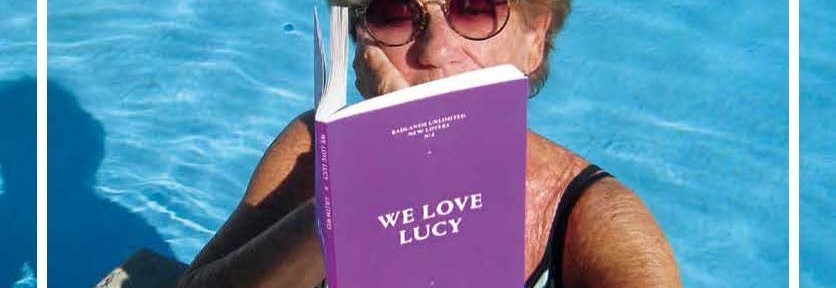

The ingredients listed in the somewhat peculiar recipes are mostly composed of plants that grow wildly without special care or cultivation, and are commonly found in Shanghai and nearby regions, with a few exceptions. Wallpaper paste, leather, and sawdust can hardly be seen as conventional food items, but they sustained human lives once upon a time through war, migration, and famine. These ingredients are featured in The Survival Project (2017—), a collaboration of the artists Rania Ho, Thy Tran, and Bryan Wu. The first volume of The Survival Project, titled FAMINE, includes a set of hand- illustrated folios, in which the artists present a series of recipes and survival techniques for coping with crises, as well as the specific scenarios of survival, drawn from research and oral histories including experiences of their families’ own. Placed together with the folios in a take-home meal box are small packets of leather, sawdust, wallpaper paste, pine needles, rice roots, etc.—the true taste of and testament to human resilience.

Most of the ingredients in the “Recipes for Resilience” do not, from a nutritional standpoint, enhance immunity to viruses and diseases for humans. But these ingredients themselves represent a strong vitality and resilience, which are inspirational for humans in times of crisis. Some of the weeds in the recipes look quite unremarkable. Their seeds take rides with the wind and settle down in whatever corners and crevices they can find in the city’s surface. Other wild plants come from another continent and are introduced to an alien ecosystem, but show more compatibility and vigor than the natives in the new environment, and become labeled as “invasive plants” (the Canadian goldenrod for instance). Wild plants have much to teach us in a myriad of ways. Don’t their vitality, adaptability, and indifference to state borders reflect an ideal political and social life for humans?

In a letter written just before his death to his lover, the Bengali poet Priyambada Devi Banerjee, Tenshin Okakura, a Japanese thinker of the Meiji period and an advocate of Pan-Asianism, described his illness as “the usual complaint of the 20th century… I have eaten things in various parts of the globe—too varied for the hereditary notions of my stomach and kidneys.” This statement and self- diagnosis is perhaps only convincing before the era of globalization and McDonaldization. In contrast to what the writer Zhang Chengzhi has called an “Asianist state of mind” when describing the internationalist mindset and sympathy towards revolutions among the Japanese civilians in the early 20th century, what surfaces, instead, from the pages in this issue of LEAP is an “Asianist state of stomach.” It is a fluid and open state that continues to evolve with people pushing and shifting its boundaries. As we can see from the author Billy Tang’s discussion of food served in Paris’s Chinatown, though the dishes bear with them distinct geographical and cultural markers, they are products of adaptation and hybridization that only gain shape in the process of migration. They surpass ideas of authenticity and provenance, and thereby echo a fluid sense of identity and territorial boundary. There are no unchanging authentic recipes from Asia, nor is there an authentic “Asia.” If we have to ascribe a character to the life forms in this expanded place that we call Asia, we hope that between the pages in this issue of LEAP, it is a spirit of resilience that transpires.

MENU

FEATURES

The Asiatique Quarter | Billy Tang

The cinematic versionists across Asia: four iterations in contemporary arts | Zian Chen

Letters from Yangon | Diana Zaw Win and Alson Haotian Zhao

Hong Kong outside the Mainstream Discourse: Fate and Chance Encounters in Johnnie To’s Films | Nelson Zhang

Katsushika Hokusai: Flâneur of the Floating World | boho

We Demand It ALL | yy?

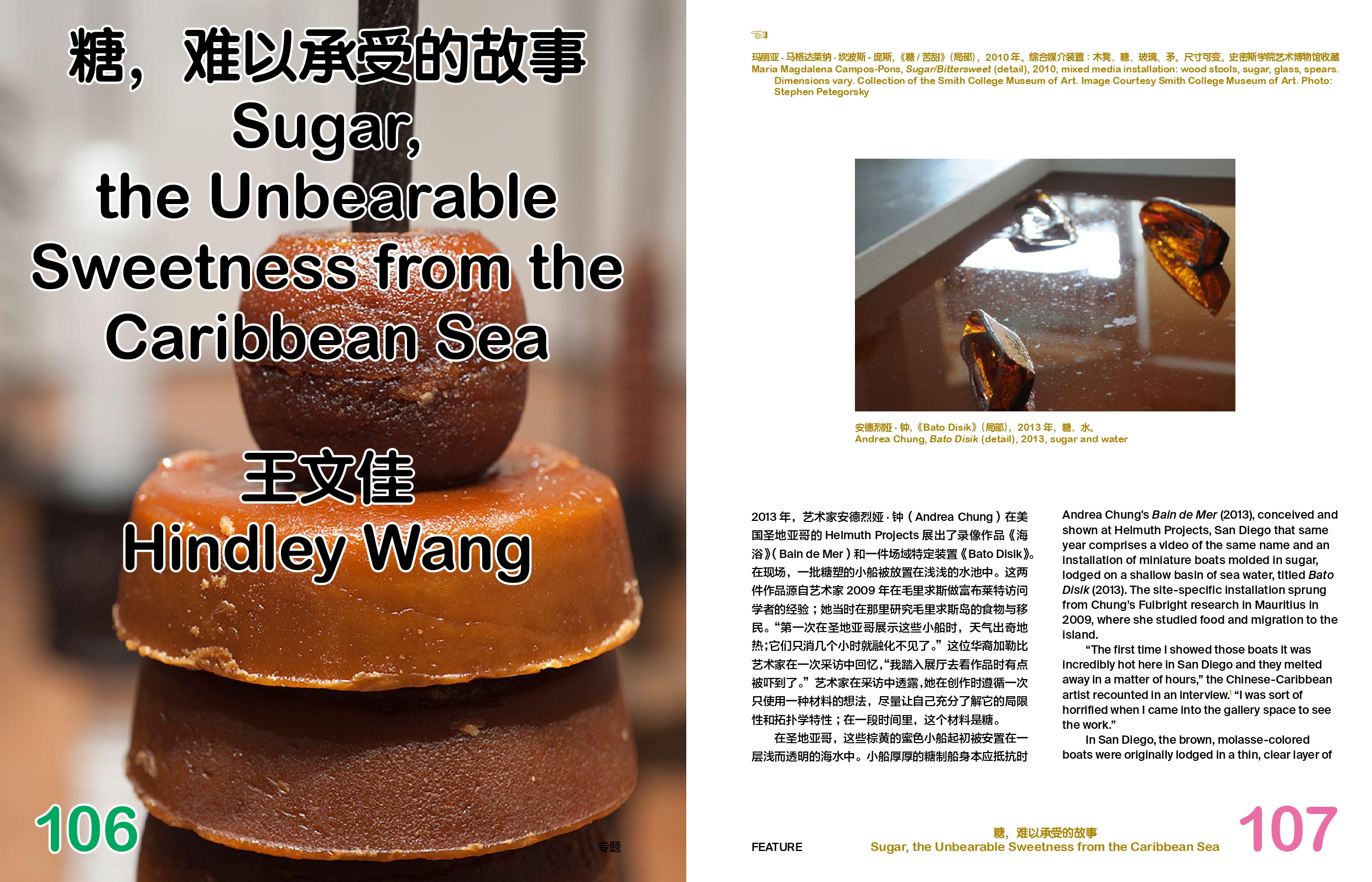

Sugar, the Unbearable Sweetness from the Caribbean Sea | Hindley Wang

You Are What You Ate | Yan Fang

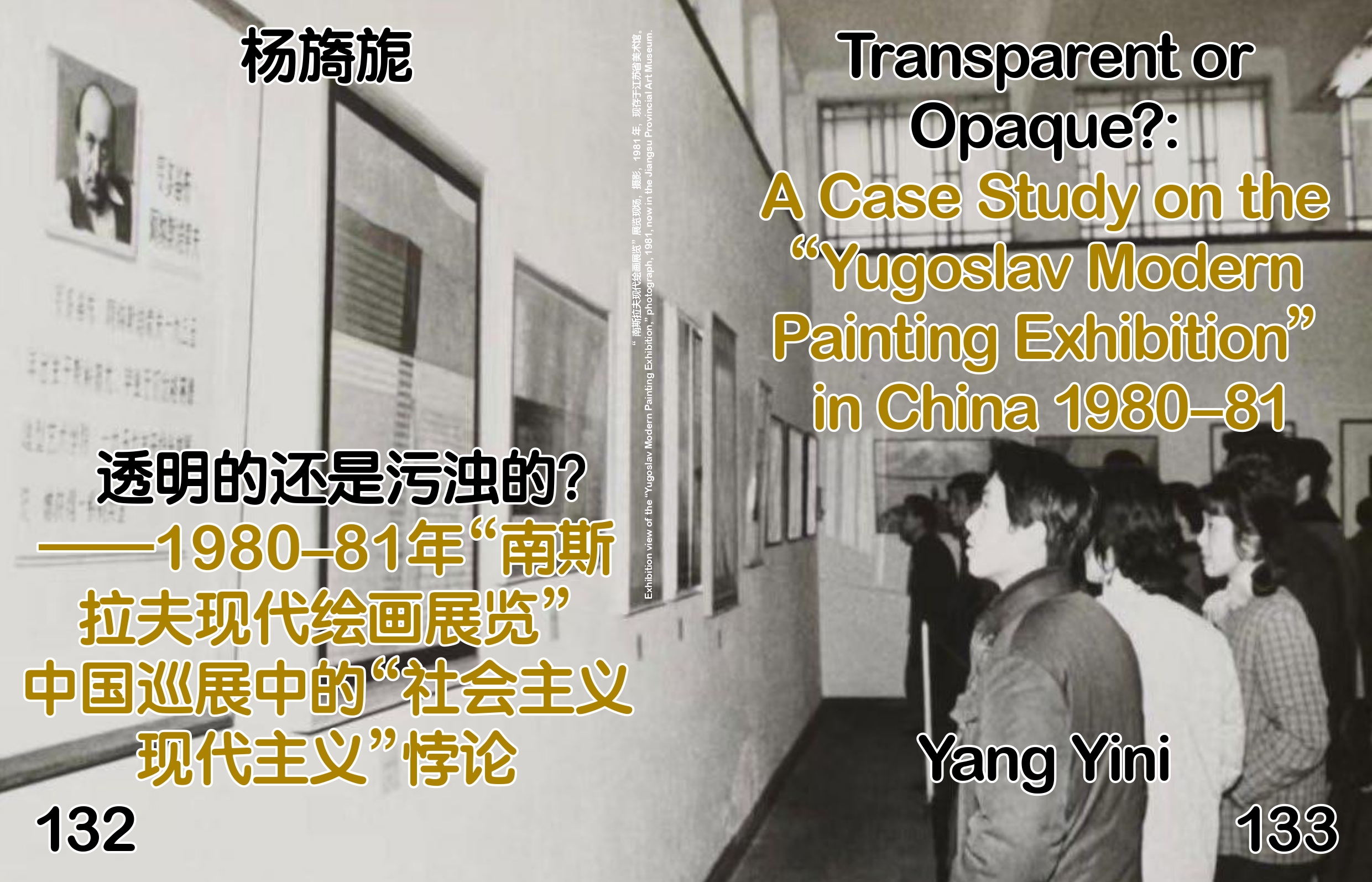

Transparent or Opaque?: a Case Study on the “Yugoslav Modern Painting Exhibition” in China 1980-81 | Yang Yini

Tokyo Embracing Meat Grinder | Zhang Duohan

Man Below the Wind–Ba Ren in the 1940s, a Chinese Marxist’s encounter with colonialism | Dui Fang

Ren Sheng and the People Around Him | Ba Ren

REVIEWS

Karrabing Film Collective: Do Rocks Listen? | Liu Mankun

Yao Qingmei: The Burrow | Ren Yue

Diriyah Biennale: Feeling the Stones | Mark Rappolt

A Show About Nothing | Ren Yue

Payne Zhu: MATCHPOOL | Jialing Sun